Farrowing on pasture. In recent years, hog farmers thought sows needed to farrow in confinement to ensure piglet survival. However, some criticize the system as promoting ulcers, sores and behaviors such as bar biting. Instead, producers are raising sows outdoors to allow them more space and access to fresh air and sunshine. Researchers and farmers have found that, with small portable huts and good pasture, they can drastically reduce the cost of production.

Outdoor pig production on a large scale is gaining a hoof-hold in the southern High Plains because of the moderate climate, relatively flat land and sparse population. In fact, the traditional cattle country of the Texas panhandle is beginning to diversify into hogs. Texas Tech University's Sustainable Pork Program began studying intensive outdoor pig production in 1993 and, in 1998, built a research farm dedicated to exploring profitable, environmentally sound systems they call 'animal-, environment-, worker-, and community-friendly.'

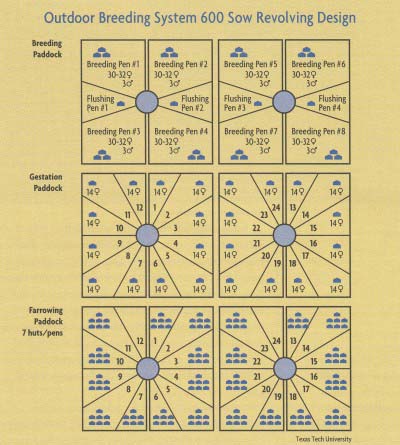

The prototype, larger than the indoor-based models, operates within a paddock system that requires about 100 acres for every 300 sows or three sows per acre. The 12-acre paddocks radiate out from a central circular area, used for handling and observation, and are demarcated by electric fence. The separate paddocks isolate breeding, gestation, farrowing and pasture growth.

Texas Tech researchers are evaluating production costs, behavior and environmental impacts, dust and microbe levels, and pork quality. Thus far, they have found improved pig health, a better work environment, less odor, less microbial activity, fewer regulatory problems and lower start-up and operating costs. More specifically, they found it costs $23.20 to raise a pig in 'intensive outdoor' production versus $31 in a typical confinement system. In that 1995 study, they found a net profit of $10.39 per pig in the outdoor system.

The institute's director, John McGlone, is sure sustainable pastured pork systems will take off once more producers learn of their environmental benefits, lower start-up costs and marketing opportunities. 'Pigs are going to be bigger than cattle on the southern Plains, and it could happen within the next 10 to 20 years,' said McGlone, who has received lots of ink in newspapers and magazines in Texas and beyond for his new production model.

A study conducted in Iowa by Mark Honeyman and Arlie Penner of Iowa State University compared economic and production data of indoor and outdoor herds. Results showed that fixed costs for the outdoor herds were approximately $3 less per pig weaned than for the indoor herds. 'There is much variation between individual producers' costs within a given system,' Honeyman said. 'A lot of producers are doing it for other reasons,' primarily the low start-up costs and improved quality of life. In the Midwest, pasture farrowing is limited to spring, summer and fall.

Large pasture farrowers have developed time-saving systems, such as arranging huts in set patterns or creating same-size paddocks so fencing and water lines can be pre-measured.

The main cost in a pasture hog system is supplemental feed, with grain accounting for 60 to 70 percent of the cost from farrow to finish. Lately, more hog producers are allowing their pigs to graze directly on grain crops to cut down on the labor and expense of harvesting row crops. ISU researchers studying the feasibility of grazing sows on alfalfa found similar costs for raising sows in confinement versus grazing alfalfa in a managed four-paddock rotational system. The grazing animals were supplemented with 1.5 to 2 pounds of corn per day. In the meantime, the alfalfa stand improved the soil.

Although an Iowa study found that outdoor farrowing produced fewer piglets per litter, the lower costs of production makes it more profitable than confinement. Honeyman said that fixed costs were $3.33 less per pig weaned outdoors, 30 to 40 percent lower overall than confinement systems. Production costs for a 250-pound outdoor market hog were $4.88 less per pig, reflecting feed, labor, repairs, utilities, health and fixed costs.

The environmental considerations, too, make this an attractive system for hog producers. While grazing through different paddocks, the hogs evenly distribute manure across the field. Pastures can be seeded or natural, and including leguminous plants like alfalfa in a rotation can improve nitrogen cycling and supply a nutritious feed for pigs. One of the biggest benefits of raising pigs outside is giving the animals access to mud, water and shade to cool themselves. McGlone recommends that producers design and build wallows for them.

Hog producers use a variety of wood, metal, or plastic huts to house their farrowing sows. Lined with bedding hay, corn cobs, cornstalks, straw or shredded newspaper the huts stay warm despite outdoor conditions. At Texas Tech, researchers use English arc-style huts to decrease the likelihood of piglet crushing.

If farrowing hogs on pasture, keep in mind:

- When choosing a farrowing hut, seek portability and an easy entrance and exit for the sow and litter.

- Pasture systems require portable waterers and feeders.

- Do not use floors in farrowing huts and move huts to fresh ground for each new litter.

- Labor is more seasonal than in confinement systems, so evaluate whether to raise one or two litters per sow each year and time group farrowing around crop chores.

- Most swine herds suffer from internal parasites that may persist in soil. Develop a rigorous parasite control program as part of a whole-herd health program.

- Fencing options vary, although some veterans recommend steel wire or electric fences that use rolls of netting on fiberglass posts for greater visibility.

- Thanks to the low start-up costs, pasture systems create an ideal way for new hog producers to get started in the industry.

Feeding hogs with pasture. New Hampton, Iowa, farmer Tom Frantzen grazes his gestating sows in permanent paddocks in the warm season. He plants corn alongside strips of pasture, partly to provide shade or act as a windbreak. Sows about to farrow graze on corn, oats and clover strips. Then, as cold approaches and the sows are ready to give birth, Frantzen moves them into a straw-bedded cattle shed. The sows over-winter in the shed, while the piglets spend the rest of their lives there. Each spring, Frantzen re-seeds his 30 half-acre paddocks and the system begins anew.

Jim and Adele Hayes raise poultry, cattle, pigs and sheep on 200 acres of pasture in Warnerville, N.Y. They believe their intensive pasture management has strengthened the operation, both by adding biological diversity and creating marketing options. During the grazing season, they rotate ruminants through a series of paddocks to provide high quality forage and to allow the pasture to re-grow before animals return to graze.

Careful attention to pasture conditions makes the system work. 'We have a sacrifice' pasture near the barn that's well fenced so it's easy to maintain the animals in there,' Adele Hayes says. 'We allow that to get destroyed if we need to,' a better option, she says, than damaging prime pasture acreage through overgrazing.