The greater the diversity of bees, the better the pollination. Honey bees are often considered the most important crop pollinator due to their sheer numbers. They live in large colonies requiring copious amounts of pollen and nectar for nourishment. Each honey bee colony contains about 30,000 bees, with a range of 10,000 to 60,000 bees, depending on the time of the year. They cover large territories when they forage, often flying 2 miles (~3.2 kilometers) or more. Through their dance language, they recruit each other to good nectar and pollen sources, and make it possible for a large number of bees to quickly find blooming flowers. They are always scanning the landscape for additional patches of flowers that bloom at different times of day to provide dietary diversity and quality. Other bee species may not have the numeric advantage of honey bees, but they have distinct traits that make them more efficient pollinators of many crops.

Different bees have different body sizes, tongue lengths, means of extracting pollen, dietary preferences, weather preferences, and life cycles. Different bees also have different foraging patterns: For example, honey bees tend to fly down a tree row while native bees often zigzag between rows ensuring cross-pollination. As another example, bumble bees are able to extract pollen through a process called buzz-pollination (see chapter 5), whereas honey bees are not able to do this. A combination of bumble bees and honey bees on cranberries would ensure that this native plant receives efficient pollination from a buzz-pollinating native bee and complete coverage of the flowers throughout the expansive bogs by the populous honey bee colonies. Having a diversity of bees means having the right tool for all occasions.

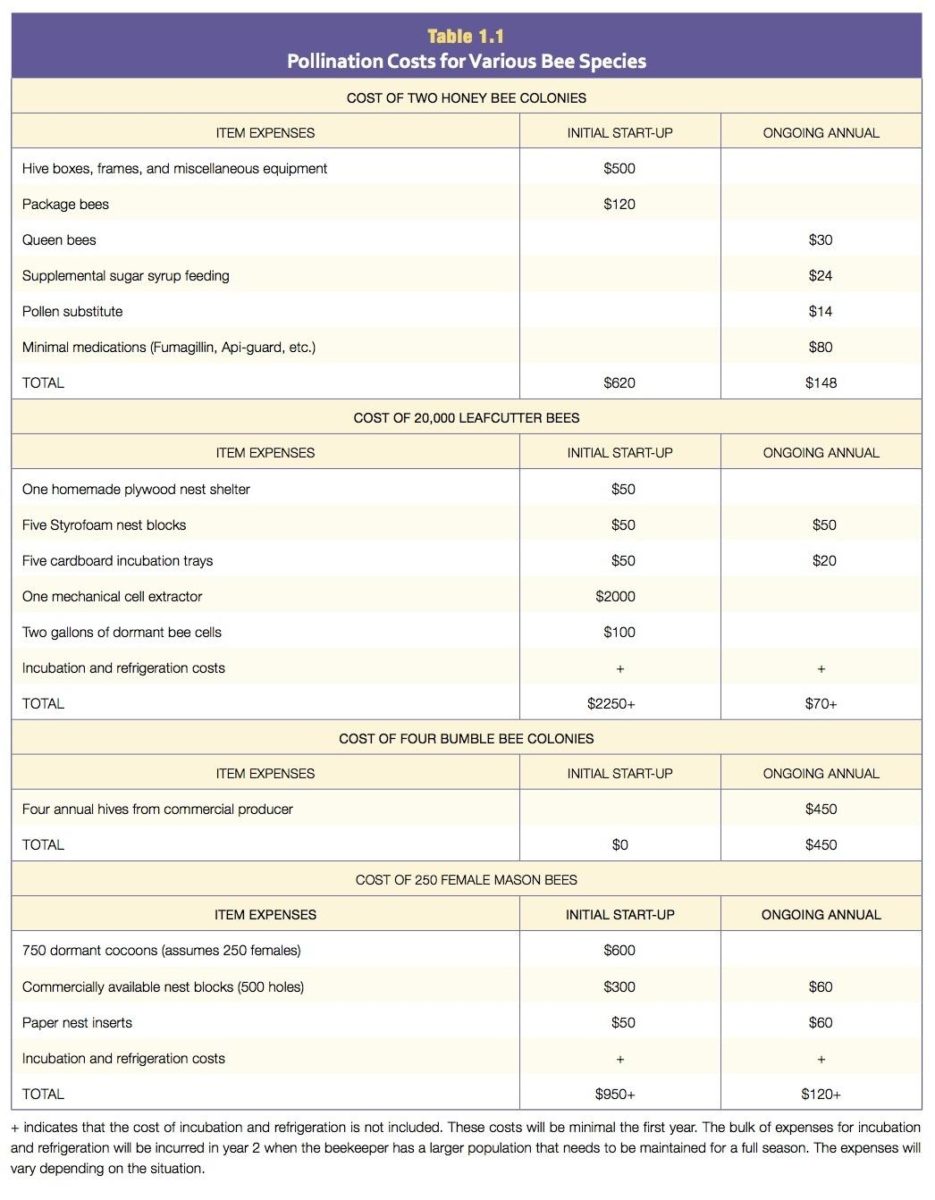

| Table 1.1 Pollination Costs for Various Bee Species | |||

| Cost of Two Honey Bee Colonies | |||

| Item Expenses | Initial Start-Up | Ongoing Annual | |

| Hive boxes, frames and miscellaneous equipment | $500 | ||

| Package bees | $120 | ||

| Queen bees | $30 | ||

| Supplemental sugar syrup feeding | $24 | ||

| Pollen substitute | $14 | ||

| Minimal medication (Fumagillin, Api-guard, etc.) | $40 | ||

| TOTAL | $620 | $148 | |

| Cost of 20,000 Leafcutter Bees | |||

| Item Expenses | Initial Start-Up | Ongoing Annual | |

| One homemade plywood nest shelter | $50 | ||

| Five Styrofoam nest blocks | $50 | $50 | |

| Five cardboard incubation trays | $50 | $20 | |

| One mechanical cell extractor | $2000 | ||

| Two gallons of dormant bee cells | $100 | ||

| Incubation and refrigeration costs | + | + | |

| TOTAL | $2250 | $70+ | |

| Cost of Four Bumble Bee Colonies | |||

| Item Expenses | Initial Start-Up | Ongoing Annual | |

| Four annual hives from commercial producer | $450 | ||

| TOTAL | $0 | $450 | |

| Cost of 250 Female Mason Bees | |||

| Item Expenses | Initial Start-Up | Ongoing Annual | |

| 750 dormant cocoons (assumes 250 females) | $600 | ||

| Commercially available nest blocks (500 holes) | $300 | $60 | |

| Paper nest inserts | $50 | $60 | |

| Incubation and refrigeration costs | + | + | |

| TOTAL | $950+ | $120+ | |

| + indicates the cost of incubation and refrigeration is not included. These costs will be minimal for the first year. The bulk of expenses for incubation and refrigeration will be incurred in year 2 when the beekeeper has a larger population that needs to be maintained for a full season. The expenses will vary depending on the situation. | |||

Take weather preferences. Honey bees will not forage much when the temperature drops below 55°F (12.8°C), when it is raining or even drizzling, or when the winds are stronger than 20 to 25 mph (32 to 40 kph). In contrast, mason bees and bumble bees will forage in inclement weather. Almond growers prefer to have the insurance of 2 honey bee colonies per acre (~ 5 colonies per hectare) rather than just 1 colony per acre (~2.5 colonies per hectare) because it often rains during almond bloom, and sufficient bees for sunny-day foraging is critical. It would be beneficial for almond growers to place nesting blocks of mason bees nearby to ensure pollination on days when honey bees don’t fly. A combination of mason bees and honey bees on almonds and apples may reduce the need to have 2 honey bee colonies per acre (~5 colonies per hectare).

One caution: Native bees can be reared to relieve some of the burden from the honey bees and their keepers. But it is very important to respect the native bees’ distribution and life cycle. Native bees are well adapted to the regions of the United States where they live. If they are mass-reared and shipped to regions outside their native range for pollination, there is a risk of also transferring diseases and parasites. Further, they may out-compete, and ultimately cause the demise of, local species. Incorporating native bees into the business of pollination can have distinct benefits, but we must use this tool wisely.

To download a larger PDF of Table 1.1: Table1.1.pdf 83.53 k

Pollination Costs per Acre, a Species-by-Species Comparison

The number of managed bees needed to pollinate an acre of flowers depends on factors such as crop type, field size, availability of wild pollinators, time of year, and which bee species you intend to manage.

Careful analysis and ongoing field observations over several seasons may be necessary to make sense of your particular situation. Even so, many extension agencies and grower organizations have consistent recommended stocking rates for bees. Standard per-acre rates, where wild pollinators are absent, often are one to two honey bee hives, four bumble bee hives, 20,000 leafcutter bees, or 250 female mason bees (for tree fruits). The per-hectare rates are approximately 2.5 to 5 honey bee hives, 10 bumble bee hives, 50,000 leafcutter bees, or 620 mason bees.

The cost of maintaining these bees includes both one-time up-front costs for equipment, and annual ongoing maintenance expenses. Exact amounts vary depending on quality and type of equipment, and how intensively the bees are managed (with medications, nutritional supplements, etc.). Table 1.1 shows several average-cost scenarios employing neither the best nor worst management practices for each species. Under optimal conditions, annual maintenance costs can be offset or even negated by hive products such as honey, wax, or the sale of excess bees.