Recent Highlights from the Northeast Region

- Farmers are the core of every aspect of Northeast SARE, and they engage in the program as teachers, learners, teammates and, as in our Farmer grant program, researchers and project coordinators. Acknowledging the importance of providing adequate funding to farmers, Northeast SARE raised the Farmer grant program maximum request to $30,000 per project to better support projects that include multi-farm collaboration, provide intensive education for other farmers and/or service providers, and conduct applied research that is replicated over multiple years or locations.

- Despite challenges created by the pandemic, Northeast SARE staff supported our grantees who were able to complete 154 projects over the past two years. These projects reached 31,589 farmers and 9,752 agriculture service providers through education and outreach; as a result, 1,530 farmers reported making changes on their farms based on what they learned.

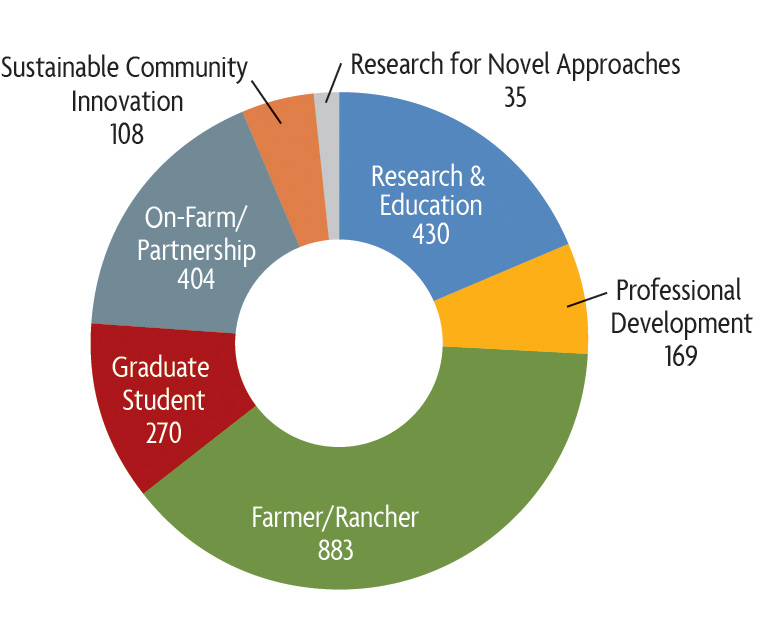

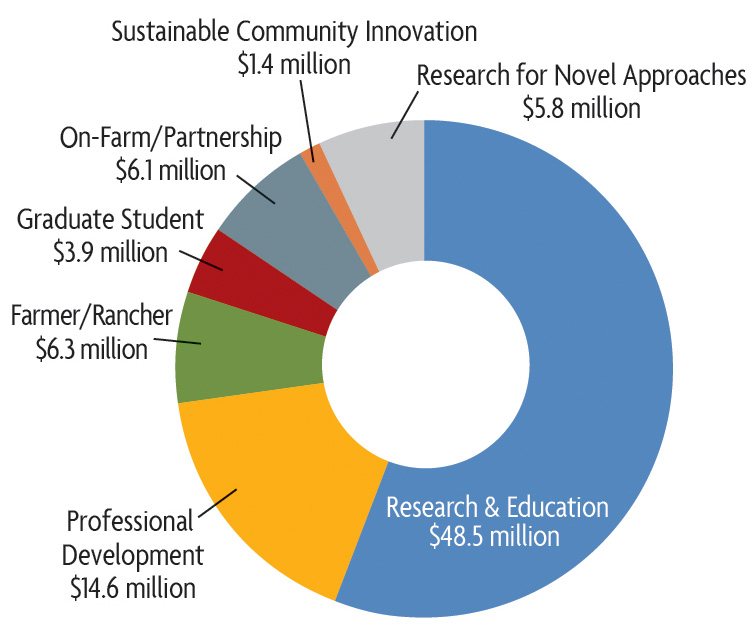

Total Grant Awards 1988-20211

2,299 Grants

$86.6 Million

Grant Proposals and Awards 2020-2021

| Grant type | Preproposals Received2 | Full Proposals Invited | Full Proposals Received | Proposals Funded | Funding Total |

| Research and Education | 144 | 65 | 55 | 21 | $3,655,067 |

| Professional Development Program | 51 | 38 | 33 | 15 | $1,933,176 |

| Farmer/Rancher | N/A | N/A | 111 | 49 | $621,689 |

| On-Farm Research/Partnership | N/A | N/A | 91 | 53 | $1,402,320 |

| Graduate Student | N/A | N/A | 131 | 49 | $721,365 |

| Research for Novel Approaches | 171 | 62 | 55 | 19 | $2,954,326 |

1These totals exclude additional direct funding given each year to Cooperative Extension in every state to support state-level programming on sustainable agriculture.

2The use of a preproposal process varies by region. It serves to screen project ideas for the larger and more complex grant programs, and to reduce applicants' proposal preparation burden as well as the proposal review burden for SARE's volunteer reviewers.

Centuries-Old Nursery Methods Prove Successful in Rice Paddies

The Challenge

Rice is a staple in the diets of more than half the world’s population, but U.S. consumers often rely heavily on imported rice from thousands of miles away in order to meet their needs. As rice has grown in popularity in the United States, farmers have begun producing the crop locally to both meet domestic demand and to cut its carbon footprint. Though a number of rice varieties can be grown in the United States, the tropical crop is somewhat at odds with the shorter growing season of the Northeast. Farmers in this region need best practices to optimize their rice production within a shorter time period than those in other parts of the country. The spring planting window is small, so successfully establishing the crop from transplants is critical.

This is what we know: grow what you eat; eat what you grow.”

Nfamara Badjie, Ever-Growing Family Farm

The Actions Taken

Using funds from a SARE Farmer grant, Dawn Hoyte and Nfamara Badjie of Ever-Growing Family Farm in Ulster Park, N.Y., set out to compare two different nursery methods for rice production in the Northeast. The research objective was to determine more robust seedling establishment methods that shorten the rice production cycle and increase rice productivity. Badjie, originally from Gambia, wanted to compare the established plug-tray method to the Diola-style field nursery, a centuries-old method of the Diola (or Jola) people of West Africa, in which field nurseries are constructed as raised beds next to rice paddies. With guidance from their technical advisor, Erika Styger of Cornell University, the team—which included Badjie, his cousin Moustapha Diedhiou and his son Malick—established a randomized block experimental design that looked at sowing and transplanting timing for both nursery methods. They used two rice varieties in the study: an Asian rice variety now commonly grown in the Northeast and Ceenowa, an heirloom rice from Africa and the farm’s commercial flagship variety.

The Impacts

Over the course of the experiment, the team hosted over 200 people at community transplant days, community harvest days, school trips, farmer organization field trips and frequent visitors. Specific impacts include:

- Enhanced productivity: The team found that, on their farm, the Diola-style nursery method resulted in more robust seedlings and required less transplanting time.

- Season extension: The Diola method allowed the farmers to extend the window to transplant and shortened the overall production cycle.

- Ease of use: The nursery method is a simplification of established strategies and does not depend on costly materials. It is easy to adopt and farmers can further adapt it to their local conditions.

Learn more: See the related SARE project FNE19-933.

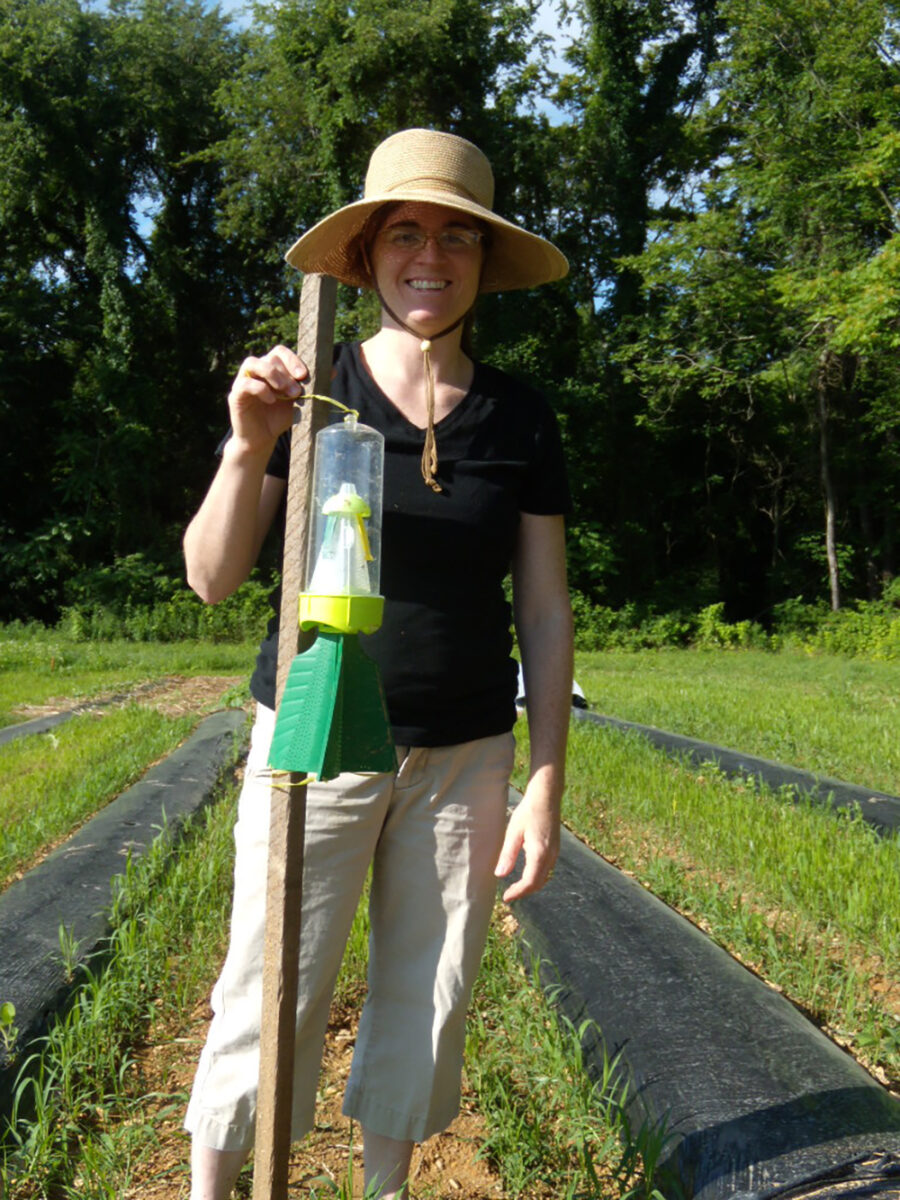

Attracticidal Spheres and IPM Help Wage War on Invasive Pest

The Challenge

Spotted wing drosophila (SWD) has become a serious threat to small-fruit growers in the United States. The spread of SWD across the Northeast in recent years has decimated crop yield and quality, with annual losses estimated to reach $718 million. This invasive fruit fly attacks healthy blueberries, brambles, strawberries and cherries by laying eggs in ripening fruit. Emerging maggots feed in the fruit causing quality decline and making the fruit unsellable. Tens of thousands of acres in the Northeast are threatened, and farmers may need up to five or more insecticide applications per season to manage the pest, causing some producers to cease production altogether. It is clear that in the war against SWD, integrated pest management (IPM) strategies that reduce the number of insecticide applications, prevent outbreaks of secondary pests and improve ecosystem services from beneficial organisms are needed.

When spotted wing drosophila densities are extremely high, other strategies ... will be necessary as well, though attracticidal spheres can provide an additional mechanism for managing this pest.”

Kevin Rice, USDA Agricultural Research Service

The Actions Taken

Researchers from the USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Appalachian Fruit Research Station secured a SARE Research and Education grant to investigate potentially effective, economically viable IPM strategies for managing SWD and to educate growers about the threat of SWD and the benefits of IPM tactics. Attracticidal spheres, which look like fruit and combine an attractant and insecticide, are not yet commercially available, but the project team partnered with seven growers to deploy these experimental devices on fields and to observe their efficacy over the course of two growing seasons. They hoped that the sphere system would reduce damage, delay the need for insecticide and increase the time between sprays. Results were mixed but promising: At low to moderate populations, the study indicated that attracticidal spheres reduced fly densities and infestations in raspberry and blueberry crops, but less so in blackberry brambles. At higher densities, the spheres needed to be supplemented with insecticide applications for appropriate pest control. The team suggested that the spheres may be used as a monitoring trap and would be a useful tool to provide a threshold indicating the need for insecticide application.

The Impacts

A key component of this grant was the research team’s outreach to small-fruit growers in the Northeast. Specific impacts include:

- Grower involvement: Nearly 400 growers attended meetings where a comprehensive SWD curriculum was provided, including the benefits and challenges of using the attracticidal sphere system. The need for monitoring traps was also discussed.

- Behavioral change: Grower survey responses indicated a strong interest in IPM tactics and monitoring tools. Subsequent surveys following the SWD curriculum showed an increase in their use. If it was commercially available, growers indicated they would likely use the sphere system on their farms.

- Commercial interest: Two meetings were held with commercial businesses that had visited the research facilities and expressed interest in making the attracticidal sphere system commercially available to farmers.

Learn more: See the related SARE project LNE16-350.