Planning Task Five

Organize and write your business plan

Implementation and monitoring

- Develop an Implementation "To-do" List

- Establish Monitoring Checkpoints

- Maintain Records

- Review Progress

By now you and your planning team have gone through a lot of work—hours of brainstorming, discussion, and research. Together you have completed more than a dozen Worksheets for each Planning Task. This final Planning Task is what you’ve no doubt been waiting for—writing up your business plan and implementing your new strategy.

Organizing and Writing Your Business Plan

Finally! You are ready to pull all of your work together into a written business plan. All along you have probably been asking: What should I include in my business plan? What should my plan look like? How should I organize my plan? Your business plan should be organized in a way that is most useful for you. It should be organized in a way that meets your internal and external planning purposes and effectively communicates with your intended audience.

There is no single format that should be used for written business plans. That said, a grand strategy that is poorly communicated will be difficult to implement. There are some critical pieces of information that can help you stay on track and that your lender, shareholders or partners will expect to see. As you discuss which business plan formats to use with your planning team, think again about how you ultimately intend to use the plan—for internal organizing or for communicating externally to a lender or potential shareholders.

If you will present your plan to others outside the business (lenders, potential clients or investors, family or other planning team members), it should convince them of the feasibility of your strategy. Therefore it should clearly convey ideas, supporting research, financial evaluation, and a contingency plan. Documentation will be critical. You will need to justify your strategy with information from your research, particularly if you intend to seek financing, solicit funds from outside investors, or to offer stock. When discussing your pricing strategy, for instance, justify why your prices are set higher, lower or even with competitive products. State under what circumstances you might change the pricing structure for each product and service to gain a stronger position in the marketplace.

On the other hand, if your plan is strictly for internal organizing, you may want to emphasize your goals, vision, mission and the overall operating plan.

A few of the most common business plan formats are shown here. Consider these with your planning team, and talk about which business plan formats seem most appropriate given your planning objectives. Use any one or a combination of these formats.

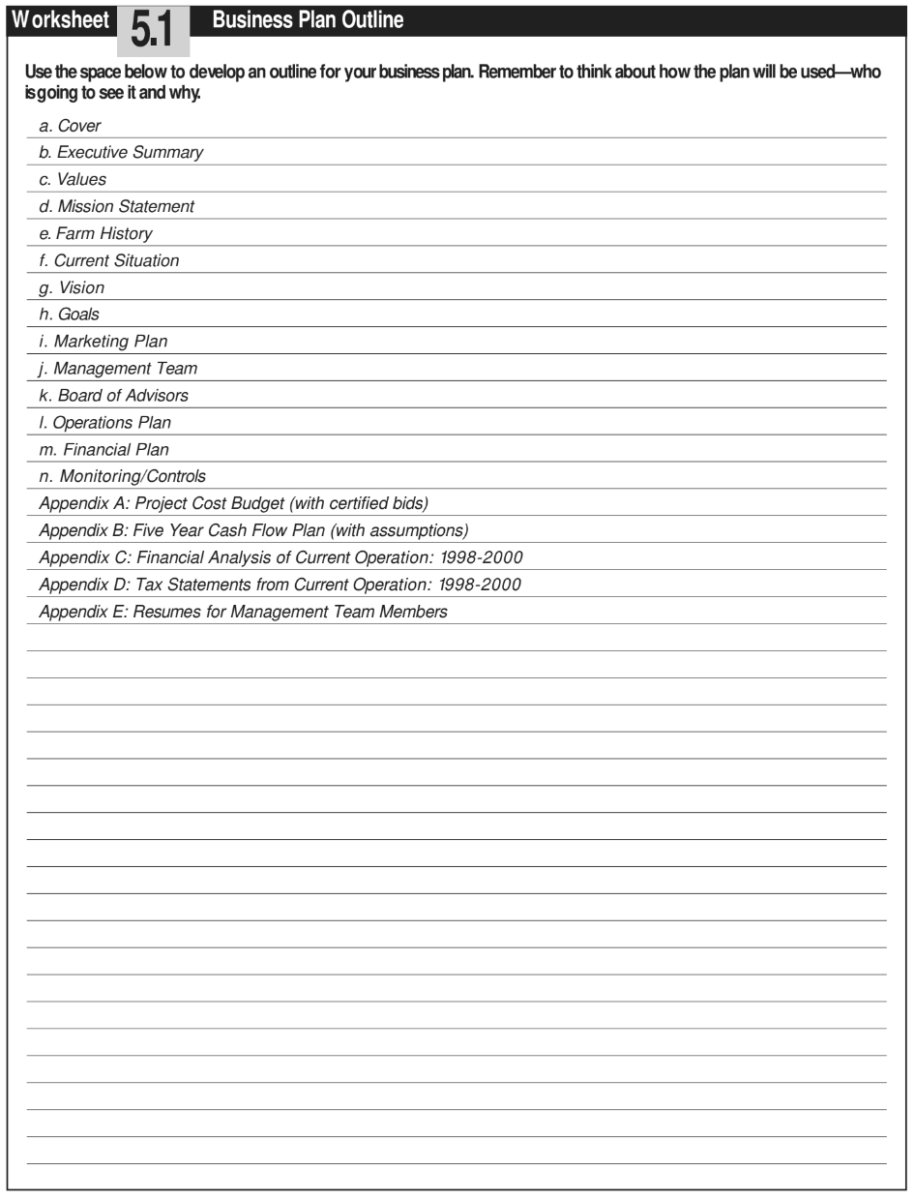

Figure 99 shows the Minar’s business plan outline. Notice that they have combined elements from the above sample outlines to create their own business plan format. Specifically, they included three years’ worth of prior tax statements, FINAN financial analyses, and a projected income/cash flow statement for the proposed processing business in an Appendix. Without this information, the Minars would not have been able to pursue the use of external funds to finance their new building and processing equipment.

Plan A: Holistic

- Cover

- Executive Summary

- Table of Contents

- Business Mission

- Business Background (History and Current Situation)

- Vision and Goals

- Key Planning Assumptions

- Marketing Strategy

- Operations Strategy

- Financial Strategy

- Management and Human Resources Strategy

- Projected Income Statement and Cash Flow

- Appendices (relevant sup port information such as market research, resumes, brochures, letters of recommendation, tax returns, etc.)

Plan C: New/Alternatives

- Cover

- Executive Summary

- Statement of Goals and Objectives

- Background of Proposed Business Idea

- Technical Description of Product

- Description of Industry and Competition

- Marketing Analysis and Strategy

- Operations Analysis and Strategy

- Human Resources Analysis and Strategy

- Financial Analysis and Strategy

- Supporting Data and Assumptions

- Conclusions and Summary

- Appendix (Marketing surveys, certified bids, brochures, etc.)

Plan E: Beginning Farmer/Start-up Business

- Cover

- Mission Statement

- Goals and Personal History

- Whole Farm Business Strategy

- Performance/Market Assumptions

- Income Projections

- Cash Flow Projections

- Risk Analysis

- Contingency Plan

Plan B: For Lender/Other Investors

(This is the format of the FINPACK Business Planning Software)

- Cover

- Executive Summary

- Farm Description (Business type and size, location, history and ownership structure)

- Strategic Plan (Mission, goals, industry analysis, competitive position, business strategy, implementation plan)

- Production and Operations Plan (Crop and livestock systems, other enterprises, risk man agement plan, environmental considerations, quality control systems)

- Marketing Plan (Marketing strat egy and resources, promotion and distribution, inventory and storage management)

- Human Resources Plan (Management team, family and hired labor, consultants, per sonnel management)

- Financial Plan (Balance sheet, asset management, projected profitability, cash flow, long range projections, historical trends, benchmarks, capital required)

Plan D: For Cooperative or Other Collaborative Marketing Group

- Cover

- Mission Statement

- Executive Summary

- Management Team

- Market Description

- Product Description

- Business Strategy

- Financial Plan

- Appendix (Articles of Incorporation, ByLaws, etc.)

Use Worksheet 5.1: Business Plan Outline (download worksheets for task 5) to draft an outline for your written plan. You might also consider using business planning software to begin drafting a written outline and plan. The AGPLAN and FINPACK Business Planning Software developed by the Center for Farm Financial Management are software alternatives that allow you to input FINPACK financial analyses directly into a business plan outline.

You should also look at some of the common presentation “pitfalls” (Figure 100) and bear these in mind as you begin to compile a written business plan.

Figure 100.

Common Presentation Pitfalls

Too much detail. There is a fine line between too little and too much detail in a business plan. Minute or trivial items that dilute or mask the critical aspects of the plan should be avoided.

Graphics without substance. With the sophisticated computer software available to the average user today, it is easy to overemphasize aesthetics while compromising substance. Graphics should be a complement to, not a substitute for, logic and reasoning.

No executive summary. Many readers of business plans will not read past the executive summary. If it does not exist, they may not read the plan at all.

Inability to communicate plan. The business plan should clearly outline the proposal in understandable terms. Monumental ideas are worthless if they cannot be communicated.

Infatuation with product or service. Although a business plan should clearly explain the attributes of the business’ key product or service, it should focus on the marketing plan. An entrepreneur can often become so intrigued by his or her ideas that he or she forgets about the big picture.

Focusing on production estimates. When making projections, the focus needs to be on sales estimates, not production estimates. Production is irrelevant if there are no buyers.

Unrealistic financial projections. Potential investors are certainly interested in profitability so that they earn a return on investment. However, unrealistic financial projections can cause a plan to lose credibility in the eyes of investors.

Technical language or jargon. Technical language, acronyms and jargon that would be unfamiliar to a person without experience in a particular industry should be avoided. The reader will be more impressed if he or she understands the plan.

Lack of commitment. The entrepreneur must show commitment to his or her business if he or she expects a commitment from others. Commitment is exhibited by timeliness and following up on all professional appointments. Investment of personal money is looked upon favorably because it shows that the owner is willing to make a financial commitment.

Implementation and Monitoring

The success of your whole farm business strategy will be, to a large extent, dependent on timely and efficient implementation. This is sometimes the hardest part for many people who worry that they haven’t done enough research or that their strategy won’t go as planned. In fact, it probably won’t. Most plans don’t realize themselves perfectly; there are always uncertainties, like those discussed when you were developing your contingency plan. But there comes a time when you must, as the well-known marketing slogan goes, just do it!

After implementation, monitor your plan. Monitoring involves tracking how your farm or business is progressing and taking action where necessary to make sure that it is on course to meet your goals. It means, as Allan Savory notes, “looking for deviations from the plan for the purpose of correcting them.” For instance, if you drew a map for Worksheet 4.2 to estimate direct market sales potential, try plotting the zip codes from your customers’ checks to see just how far your customers travel to purchase your product. What does this tell you? Is your marketing strategy effective? Are you reaching your target market? Are there households within 20 miles of your business that aren’t customers but who should be? You’ll also want to ask yourself how does your work, accomplishments, output, etc., compare with desired goals and projections.

In order to track your progress, you should develop an implementation “todo” list, establish checkpoints, keep records, and review progress with planning team members, board members, or management staff.

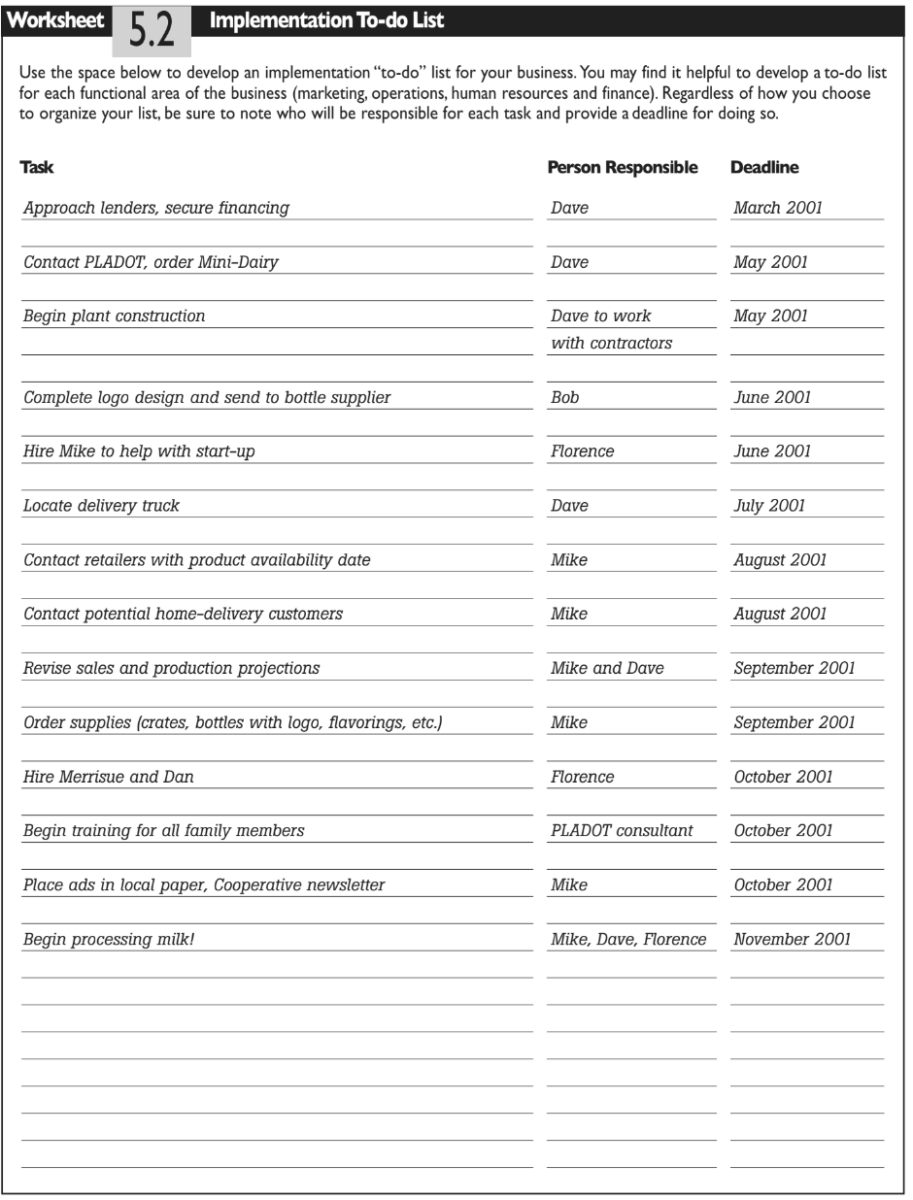

Develop an Implementation "To-do" List

Describe how your strategy will be implemented, indicate who will be responsible for completing implementation tasks, and specify deadlines for completing each task. In other words, create a “to-do” list for strategy implementation. This will help you stay on course as you begin implementing your whole-farm strategy.

A portion of the to-do list created by Dave and Florence Minar for their proposed processing business is presented in Figure 102. The first item on their to-do list, of course, is to contact lenders and secure financing for the new business strategy. Once financing was available at interest rates that allowed adequate repayment and profit, the Minars were ready to quickly move down their list and begin readying the business for its first day of milk processing.

Put someone in charge of overseeing the entire implementation process— particularly if a major change is being made or when several family members/partners are involved.

Use Worksheet 5.2: Implementation To-do List (download worksheets for task 5)to create a simple Mike Mike, Dave, Florence to-do list. Make sure that you have the staff and time to successfully implement your business plan.

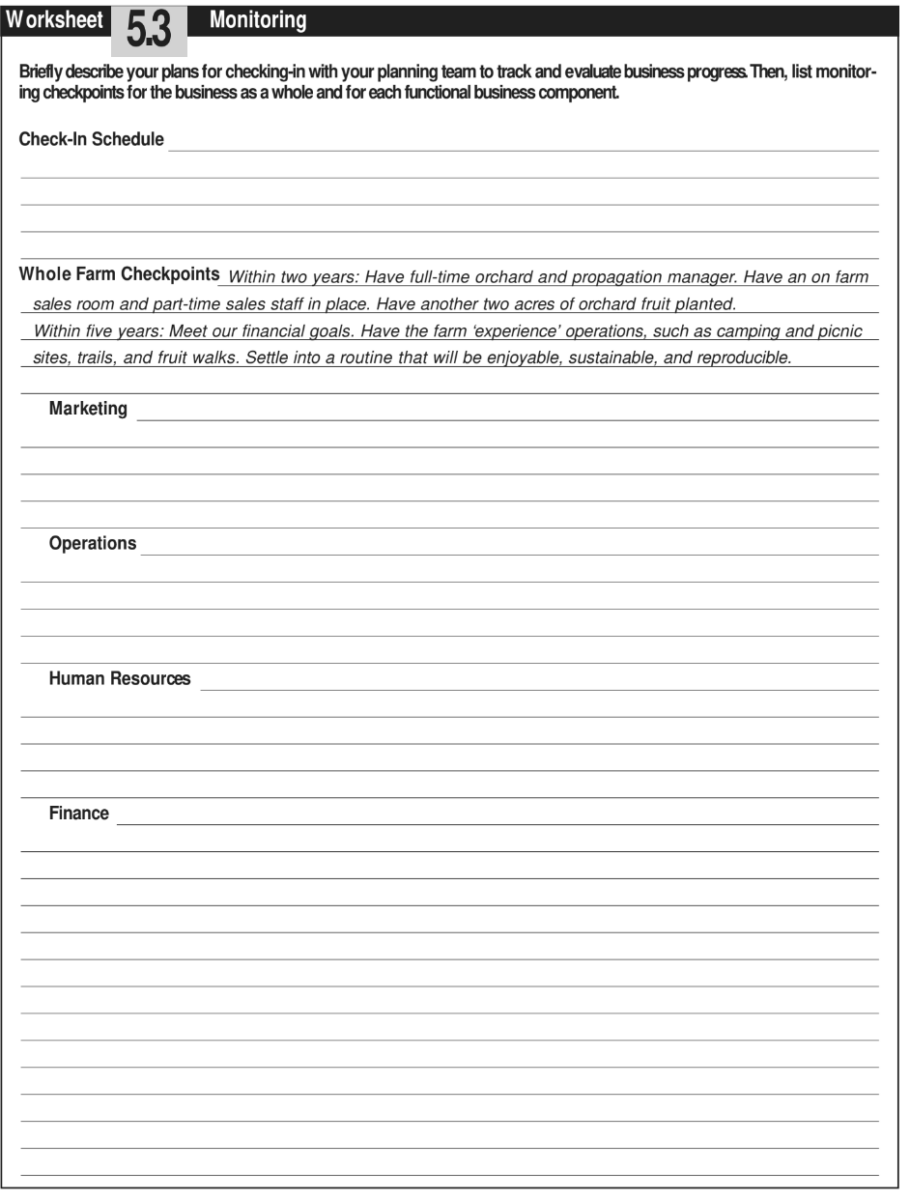

Establish Monitoring Checkpoints.

Next, develop a list of monitoring checkpoints. Monitoring checkpoints, also called “critical success factors” and “objectives,” are those key events or accomplishments that must occur for your business to succeed. They measure progress and act as “early warning”signals that alert you to when, where, and how your goals and plans may need to change. In this way, note authors of the Land Stewardship Project’s Monitoring Tool Box, “monitoring can act as a springboard for finding creative ways to adapt your management.”

Monitoring checkpoints are typically more detailed than your goals for the whole farm and are based on a shorter time frame. Monitoring checkpoints can be specific production targets, sales objectives, profit goals, wildlife counts, or whatever measure of success is important to you and your planning team.

Frank Foltz, owner of Northwind Nursery and Orchard, summarized monitoring checkpoints for his business into two- and five-year time frames. His checkpoints, reproduced above, should be easy to monitor as Frank and his family implement their plans.

Following are other examples of monitoring checkpoints taken from the business plans prepared by Mabel Brelje, Mary Doerr, Dave and Florence Minar, and Greg Reynolds:

- Increase Community Supported Agriculture share sales by 20 percent this year

- Pay down debt by 15 percent this year

- Provide health care for all employees by December

- Identify buyer for farm within two years

Of course, the goals that you outlined in Planning Task Three (Vision, Mission and Goals) can be used as long-term critical success factors. Likewise, the financial ratios described in Planning Task Two (History and Current Situation), as well as your long-range income and cash flow projections developed in Planning Task Four (Strategic Planning and Evaluation), can be used as monitoring benchmarks from which to track and compare the financial performance of your business over the long-run. In fact, FINFLO—the cash flow planning piece of FINPACK—includes a “Monitoring Worksheet” to help you monitor planned versus actual cash flows during the year. By monitoring cash flow performance, it may be possible to adjust your operating plan before experiencing financial adversity.

If you are interested in tracking natural resource benefits, check out the Monitoring Tool Box developed by the Land Stewardship Project. This publication provides Worksheets and practical suggestions on how to monitor some of those intangibles (quality of life), as well as the tangibles, (stream and soil quality).

Figure 104.

Record Keeping Ideas

You may decide to maintain records for everything from songbird counts to input expenses. Below are examples of just a few of the record keeping possibilities for each functional area of your business.

Marketing. Maintain a customer database to track purchases, feedback and customer location. Addresses, phone numbers and email contact information for each customer can be obtained from personal checks or signup sheets at farmers’ markets or local events.

Operations. Track the productivity of each enterprise—such as yields or rates of gain—as well as other indicators like pasture composition, soil composition, the protein content of feed, and wildlife populations on your farm. Use a simple notebook or chart to record this information for future use.

Human Resources. Record the number of hours that you spend on the job. This can be time consuming in itself, but one way to get a gauge of your labor time is to track your hours during a “typical” week or month—one that is representative of the different tasks that you perform during a typical year for each enterprise. From these records, you can estimate time spent working on the farm for the entire year.

Finances. Manual or computerized accounting systems can be used to develop an annual balance sheet, accrual income statement, monthly cash flow, enterprise cost/profit center reports, and a financial ratio summary (FINPACK, Quicken for Farm Financial Records or Farm Biz).

Use Worksheet 5.3: Monitoring (download worksheets for task 5) to develop a checklist or calendar of timely objectives to help you track the immediate progress of your business.

Maintain Records

Keeping careful records! At the end of the year, with good records in hand, you will be able to compare actual yields, costs and sales to those projected figures in your business plan as well as any other monitoring checkpoints established by your planning team.

Records can be formal accounts of financial performance, productivity and sales. However, records can also take the form of “field” observations to help you track changes in wildlife populations, plant species and hours on the job. It’s up to you to decide what records to keep depending on the type of management feedback you require.

Review Progress

Finally, you may want to develop a written monitoring schedule that outlines when you will review your plan and checkpoints with planning team members—once per month or season? During a slow time of the year? At a regularly scheduled family retreat? Arrange a time when planning team members can meet to discuss what about the business has been successful and what has not using your critical success factors, goals and financial projections or ratios as guides.

If you were unsuccessful in some areas or in terms of several objectives, try to understand why. Ask whether or not circumstances have changed within the business or externally in the industry and market, or if your initial projections were unrealistic. Use both your successes and failures to learn more about your business. Time brings experience and makes you wiser about your business and the industry. For example, after a year, you may have a better sense of market prices or production potential. Always remember to adjust your prices and output projections as you gain experience.

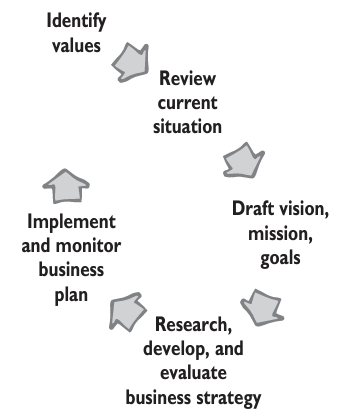

Next, take time to re-evaluate your business plan. You’ve come full circle in the planning process. Review your goals, take stock of the business’ current resources and competitive environment, and make strategy adjustments if necessary. Then you’re ready to develop new checkpoints for your next season/ year in business.

Next, take time to re-evaluate your business plan. You’ve come full circle in the planning process. Review your goals, take stock of the business’ current resources and competitive environment, and make strategy adjustments if necessary. Then you’re ready to develop new checkpoints for your next season/ year in business.

Epilogue - Cedar Summit Farm, 2010

Business plans are often written with good intentions and much confidence, but how often are they put into action? What challenges are encountered during business start-up or how do business owners handle unanticipated “bumps in the road?” And, perhaps most importantly, how often do business plans lead to business success?

After nearly ten years of operation, Cedar Summit Farm (CSF) is a thriving, value-added business with wholesale product distribution to 80 retail stores throughout Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and Iowa. Dave and Florence Minar continue to manage the farm and processing business along with all five of their children, their childrens’ spouses, and several grandchildren. Together the extended Minar family process milk; package, and deliver products; staff the on-farm store; conduct in-store demos; maintain the company website; perform accounting services; and manage crop production. A full-time herd manager and other part-time staff handle much of the livestock operations.

Meeting Goals

The Minars’ original business goals included: (1) building a small milk processing plant on the farm with a retail store and drive-up window; (2) processing all of the milk produced on farm as Cedar Summit Farm products within five years of start-up; (3) processing and retailing all dairy products to local customers (25-mile radius) within five years; (4) continuing to grow direct meat sales; (5) providing full or part-time employment to any family member who desires to work in the family business; (6) providing educational opportunities and benefits such as health insurance and a 401K plan; (7) purchasing supplies locally when possible; (8) packaging products in the most economical and environmentally sound way possible; and (9) marketing products that make the family proud.

Nearly all of the Minars’ original nine goals have been met through the new, on-farm milk processing business. After obtaining financing and construction permits, the processing plant and retail store were built in 2001. Since then, the Minars have been gradually growing sales and processing a greater share of the milk from their 150 cow dairy herd. Beginning in 2007, five years after the creamery bottled its first gallon of milk, the Minars reached their production goal and began processing 100 percent of their milk on the farm during peak sales periods. Approximately 15-20 percent of all products are sold locally to nearby residents through the on-farm store with the remainder marketed at the wholesale level within the region.

Dave and Florence now raise all of their own herd replacements and finish steers on a combination of their own pasture as well other leased and rented land for direct sales of beef products at the farm store. All of their children are involved in the business—most are employed full-time and receive market wages in addition to health insurance. All other salaried employees also receive health insurance. The majority of supplies (such as cartons and labels) are purchased locally from Minnesota suppliers. Approximately two-thirds of all milk is packaged in returnable glass bottles which Dave and Florence consider environmentally responsible.

When asked if they feel good about the business, both Dave and Florence say emphatically that they are not only proud of their product quality and the decisions they’ve made, but they are also genuinely warmed by the “support” they’ve received from local customers—customers who have remained loyal to the CSF products during difficult economic situations.

Revising Strategies

The Minars faced several significant marketing and financing challenges during their startup years. Despite their best efforts to make home delivery a success, Dave and Florence were forced to abandon this distribution strategy after two years. Internal constraints, such as a failure to find a personable, efficient delivery person combined with the external rise in gas prices and neighborhood demographics which would not support a corresponding rise in product prices, made the home delivery strategy unprofitable. This was surprising and disappointing for the Minar family as the home delivery strategy was originally forecast to generate the lion’s share of new business income.

By contrast, sales at the wholesale level (to retailers) were growing as were sales at the CSF on-farm store. “We had to shift gears a bit,” says Dave. “It wasn’t what we planned on but it was working.” While Dave and Florence redirected their marketing efforts away from home delivery toward wholesale, additional financing was required to manage cash flow needs. “It was a stressful time,” recalls Florence. “We were under-capitalized. But we made it by being flexible and, quite honestly, by foregoing our own income for a while."

Two additional, yet significant, marketing challenges arose during the Cedar Summit Farm start-up years. First, due to new competition from another local creamery using glass bottles, the Minars were forced to further differentiate their product by becoming certified organic. Second, the Minars were approached by several retailers who wished to stock CSF milk, but did not have the staff or storage capacity to handle returnable glass bottles. In response, the Minars decided to offer waxy cartons in addition to glass-bottles for their milk. Today, approximately one-third of all CSF milk is sold in cartons.

A New Business Plan

When asked if they still use their business plan, Dave and Florence shake their heads “no.” “We don’t need to,” says Florence. “We know it by heart!” But, they say, they will be rewriting their plan soon—to lay the foundation for the next phase of their business—growth and, eventually, the transfer of day-to-day business management to the next generation. “We already have ideas brewing,” says Dave. “We’re excited about growing the business … and taking a little time off.”