Planning Task Four

Develop a business strategy:

Marketing Strategy

- Markets

- Product

- Competition

- Distribution and Packaging

- Pricing

- Promotion

- Inventory and Management

- Develop a Strategic Marketing Plan

Operating Strategy

- Production Management

- Regulations and Policy

- Resource Needs

- Resource Gaps

- Size and Capacity

- Develop a Strategic Operations Plan

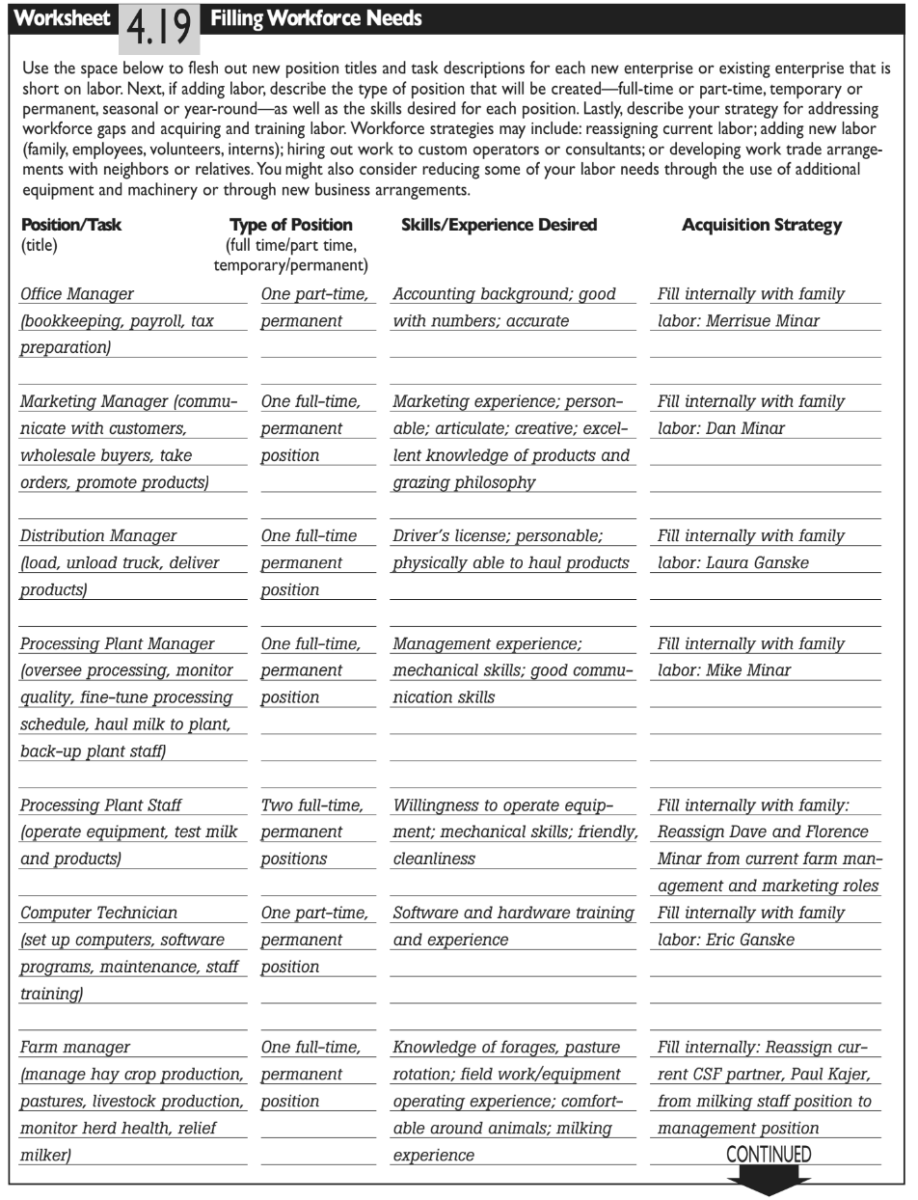

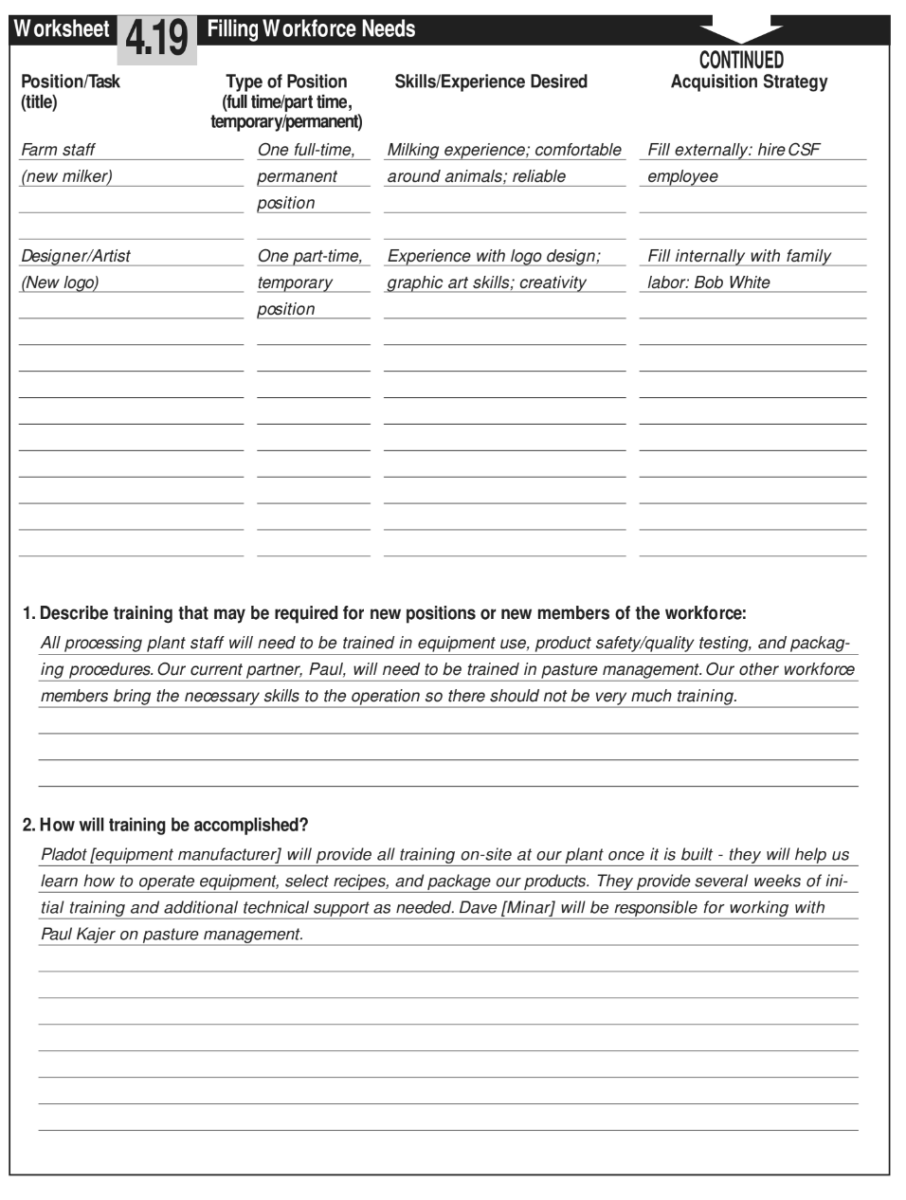

Human Resources Strategy

- Labor Needs

- Labor Gaps

- Compensation

- Management and Communications

- Develop a Strategic Human Resources Plan

Financial Strategy

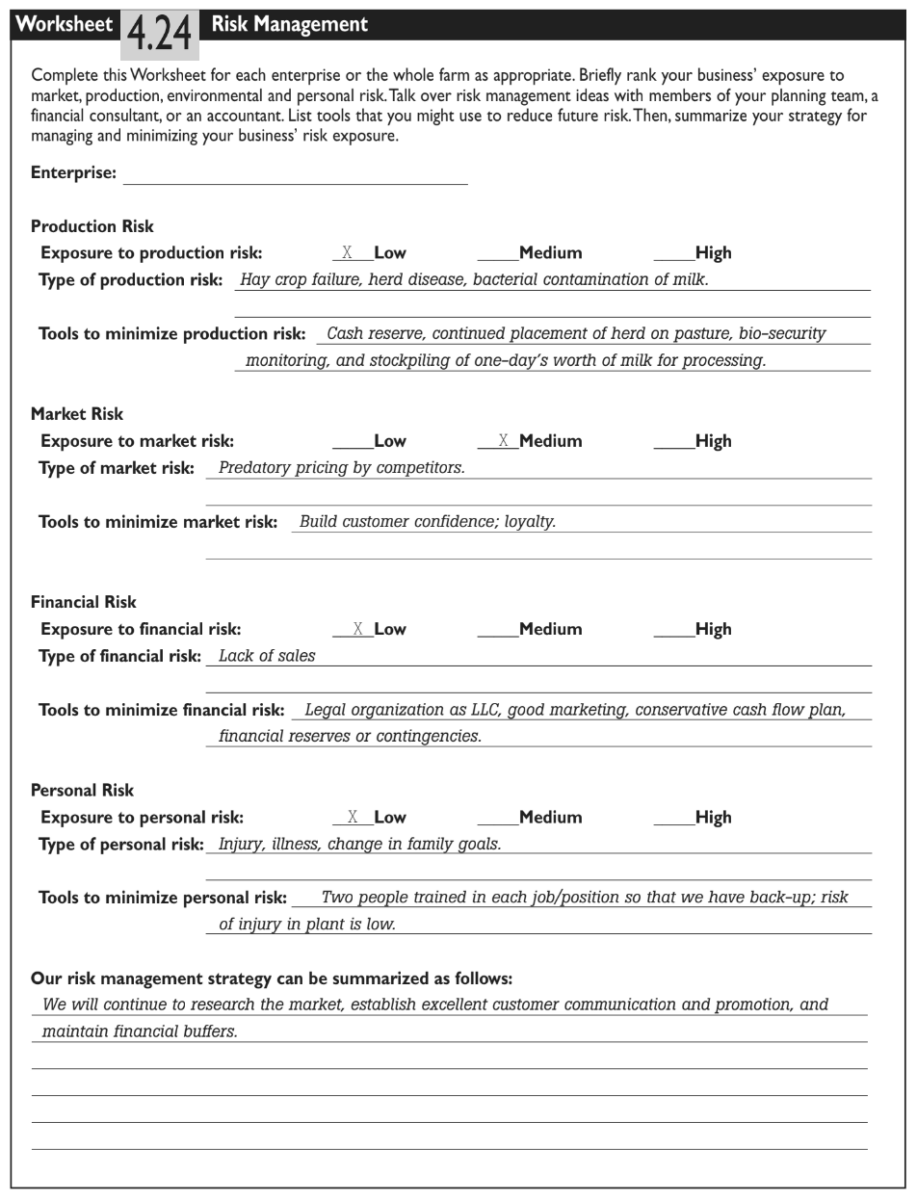

- Risk

- Organizational Structure

- Finance

- Develop a Strategic Financial Plan

Whole Farm Strategy

Choose the best whole farm strategy

Develop contingency plans

Develop the Strategic Planning section of your Business Plan

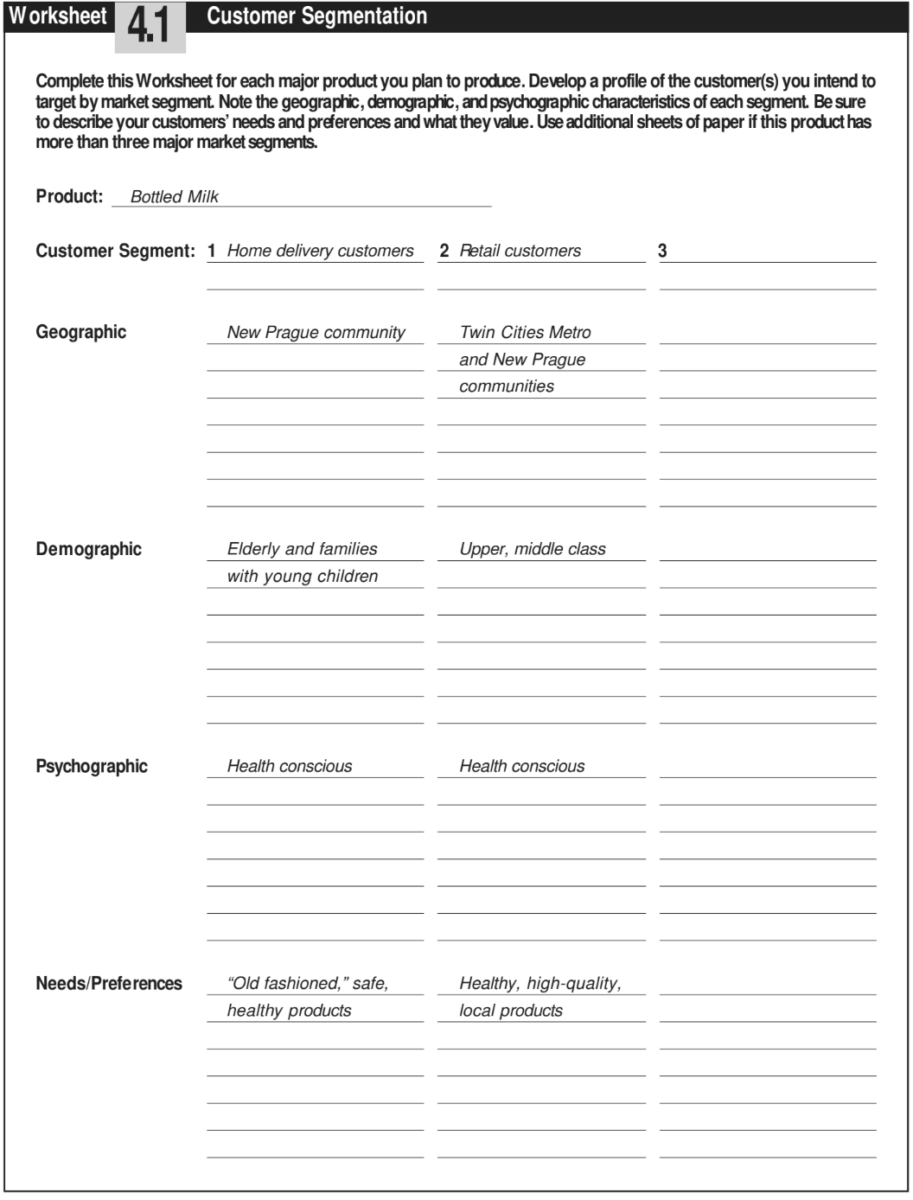

Strategy is defined as a “careful plan or method for achieving an end.” That’s your challenge in this Planning Task. You’ve envisioned your future, based on your goals and values, so you know what you want the “end” to look like. Now you need to take the time to carefully think through the steps you can take to get there. Think about planning a trip. You know your destination—but what’s the best way to get there? You could fly, take a train, or drive. You might sketch out the trip for each possibility, by researching the plane and train schedules and consulting roadmaps. You develop a “careful plan.” Then you evaluate. You weigh many factors—the cost of each, your enjoyment using each of those means, possible problems such as road construction, delays at airports, and so forth. Then you choose the best option for you. Essentially, that is what you will be doing in the five steps of this Planning Task: Developing a plan to achieve your envisioned business, weighing it against other options, considering how the situation might change (market, interest rates, labor, etc.), and how those changes would affect your plan.

Dave and Florence Minar defined very specific personal, family, and business goals for Cedar Summit Farm. Their goals are tied to a set of values concerning family, environment and community that have grown through time. Their challenge in this Planning Task was to develop a whole farm strategy that, over the course of five, ten or more years, would live up to their values—a strategy that would move them toward their goals, by taking advantage of current business strengths and perceived market opportunities.

If you have completed the Worksheets for the preceding Planning Tasks, then you have already laid the foundation for strategic planning. Your job in Planning Task Four is to begin building a whole farm strategic plan for your future on top of that foundation.

In Planning Task Four you will:

- Develop a business strategy.

- Evaluate strategic alternatives.

- Decide on a whole farm strategic course of action.

- Develop contingency plans.

- Develop the strategic section of your business plan.

Business strategies are realistic actions that communicate how you plan to

reach your goals. There are an endless number of potential strategies that can

be developed for each functional area of the business or the farm as a whole.

Your task will be to narrow the list of possibilities to those marketing, operations, human resources and financial strategies that best address your critical planning needs, and are compatible with your values, vision and goals. A simple rule of thumb to follow when developing strategies is to take advantage of your business’ internal strengths. “A farm’s strategy ought to be grounded in what it is good at doing (i.e., its strengths and competitive capabilities).”

We suggest beginning your strategy research and development with the functional area that most clearly addresses your critical planning need or whole farm strategy idea. Then move on to the other functional areas. Dave and Florence Minar began their strategy research with human resources. They took a look at how on-farm processing might address their critical planning need to provide new jobs and income for family members. They then studied the market to gauge sales potential and competition while simultaneously researching equipment options and processing capacity. The last thing they developed was a financial strategy.

As you research and develop your business strategies, you will consider many of the same marketing, operations, human resources and finance questions that you first considered when you assessed your current situation in Planning Task Two. This time around involves more research. You will answer these same questions, using educated guesses rather than actual experience.

Once you have identified a set of feasible strategic alternatives for each functional area of the business through research and evaluation, you will link them together into a system-wide, whole farm business strategy complete with contingency and implementation plans. When you are done with this Planning Task you should be ready to draft your business plan.

This is a very involved Planning Task—take your time. Most importantly, consult planning team members and get outside help when you need it. Don’t

expect to be an expert on everything (marketing, operations, people management, legal issues, financial analysis), particularly when researching a new idea. The Minars created a board of advisors, in addition to planning team members, to help them identify and evaluate strategic marketing and operations alternatives. Their advisors included a local banker, farm business management consultant, meat processor, clients, and other farmers. Consult the “Resources” section at the end of this Guide for assistance in locating outside help whenever and wherever you need it.

Because each business is unique, every strategic need cannot be addressed in this Guide. Clearly, most of your strategy work will take place in person with your planning team members. Worksheets are provided to help you flesh out and record the details of your business strategy alternatives.

Develop a Business Strategy

This first step in your strategic plan, Develop a Business Strategy, is where you’ll spend the majority of your time and effort for this Planning Task. You will consider all four functional areas, and you’ll consider many variables within each of those areas. We’ll remind you of where you are in the process from time to time. In the sections that follow, you will have the opportunity to identify and research alternative strategies for each functional area of the business—marketing, operations, human resources and finances. Begin by returning to your Whole Farm SWOT Analysis (Worksheet 2.18) to review the internal strengths of your present business and any perceived industry opportunities, as well as the internal weaknesses and external business threats you and your planning team identified. Good business strategies always take advantage of current business strengths and market opportunities. At the same time, a solid business strategy will address current weaknesses and perceived threats. With your SWOT Analysis in hand, you are ready to begin developing specific marketing, operations, human resources and finance strategies for the business.

Marketing Strategy

The marketing component of your business strategy will determine, in large part, the success of your business. As marketing consultant Barbara Findlay Schenck said: “Without customers, a business is out of business.”Your marketing strategy is about defining your customer or target market and tailoring your product, pricing, distribution and promotion strategies to satisfy that target market. Marketing experts warn that businesses that are product oriented—those that try to sell what they can produce without first looking at customers’ needs—risk developing a product that won’t sell. Instead, most successful businesses are customer oriented—they design marketing strategies around the needs of their customers.

At the end of this step, you should be able to confidently answer the following questions:

- Markets: Who are our target customers and what do they value?

- Product: What product will we offer and how is it unique?

- Competition: Who are our competitors and how will we position ourselves?

- Distribution and packaging: How and when will we move our product to market?

- Prices: How will we price our product?

- Promotion: How and what will we communicate with buyers or customers?

To complete the Marketing segment of the Develop a Business Strategy step, you will address the issues shown at right.

As you begin your research, track any expenses associated with the marketing strategies that you develop. You will be asked to record this information in your Marketing Strategy Summary (Worksheet 4.9).

markets: Who are our target customers and what do they value?

Most marketing plans begin with a description of the business’ target market, or its potential customers. Your first task in building a customer strategy is to identify your target market. Target markets are most commonly characterized as either individual households or businesses.

Direct marketing to individual households or customers can be performed on a small scale. This form of marketing tends to be more profitable than business-to-business marketing because of value-added opportunities and the lack of middlemen. Most direct market products are consumer goods or services. Popular direct market opportunities include Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), Pick Your Own (PYO) and farmers’ markets.

Business-to-business marketing typically involves sales of a raw commodity or product that will be used as an input. Traditional commodity producers almost always practice business-to-business marketing where customers include grain companies, processors, packers and millers. Today’s specialty or differentiated commodity producers, however, are learning to build in more profit by responding directly to market demand for unique products, such as tofu grade soybeans, high oil corn, grass-fed livestock, organic feed, and heirloom vegetables. Don’t overlook today’s business-to-business opportunities to contract and market specialty commodities.

Figure 37. Market Segmentation Alternatives

Geographic:

Segmenting customers by regions, counties, states, countries, zip codes and census tracts.

Demographics:

Segmenting customers into groups based on age, sex, race, religion, education, marital status, income and household size.

Psychographics:

Segmenting customers by lifestyle characteristics,

behavioral patterns, beliefs and values, attitudes about themselves, their families and society.

That said, if you plan to market a raw commodity directly to an elevator, packer or overseas broker, your marketing strategy will be very different (and presumably less intensive) than that of someone who is looking at direct marketing a differentiated product to a well-defined market of individual customers.

In order to fully define your target market and corresponding customer strategy, you will need to identify your target market segment (who your customers are and what they value) and sales potential (how much they are willing to buy). This research is critical for building your business. Marketing author Michael O’Donnell notes that one of the most common planning mistakes is failure to fully “understand the market makeup and what segment the company will concentrate on.”

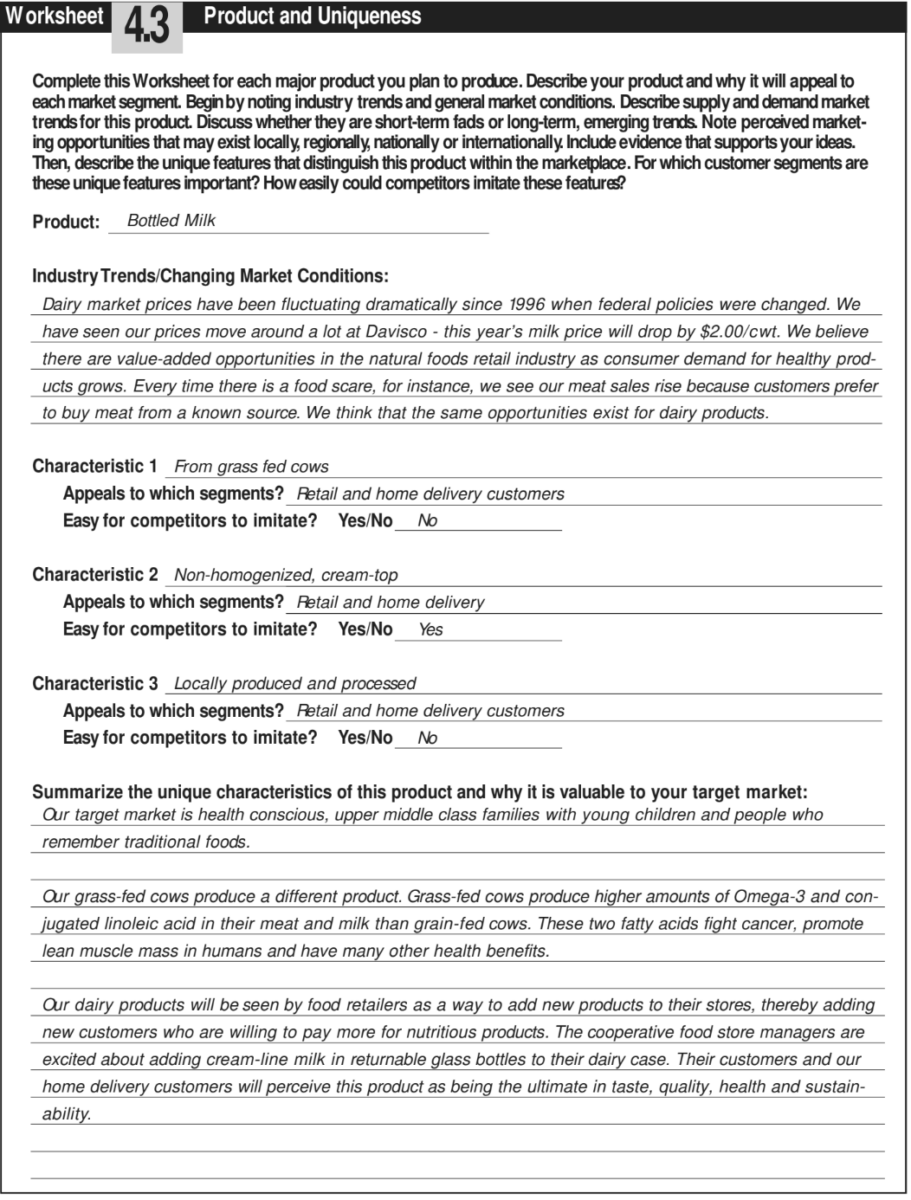

Segmentation. Dave and Florence Minar identified. “individuals” (as opposed to other businesses) as their target market for Cedar Summit Farm dairy products. This target market was very different from their customer at the time, Davisco, which acted as a distribution intermediary by purchasing bulk milk for further processing. Consequently, when the Minars began the planning process, they had to conduct substantial research to learn about their new target market size, geographic location, purchasing patterns and preferences.

This process of identifying customers’ preferences and dividing the large target market into submarkets is called market segmentation. By identifying and targeting specific market segments you should be able to develop more effective packaging, price and promotion strategies.16 Markets can be segmented in a variety of ways. The most common forms of segmentation are by demographic, geographic, psychographic and product-use characteristics.

For instance, a market can be segmented into domestic and international subgroups if you are planning to market organic soybeans like Mabel Brelje; or into on-farm and off-farm buyer groups for gourmet cheese like Dancing Winds Farm owner Mary Doerr. Your market can also be segmented by the frequency of customer purchases, as considered by Riverbend Farm owner Greg Reynolds for weekly versus monthly vegetable customers.

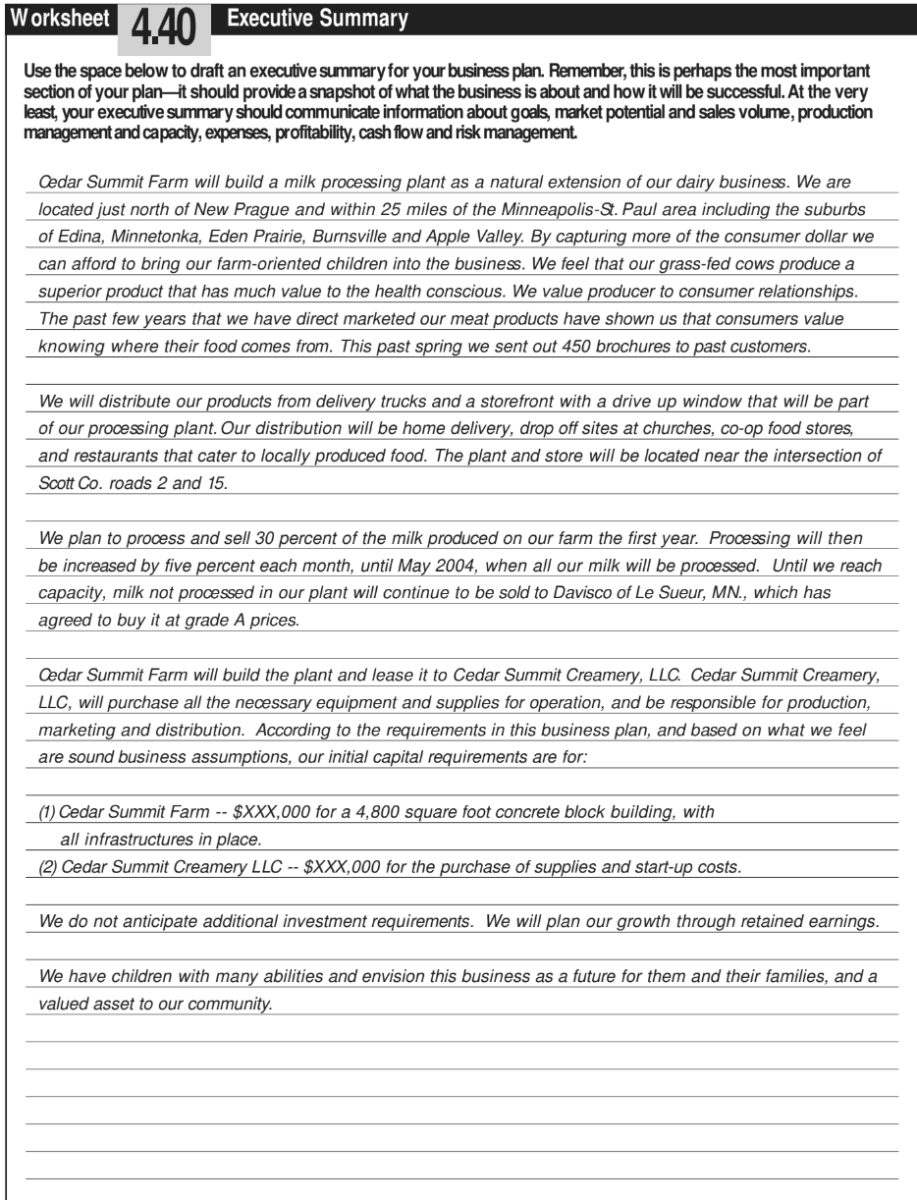

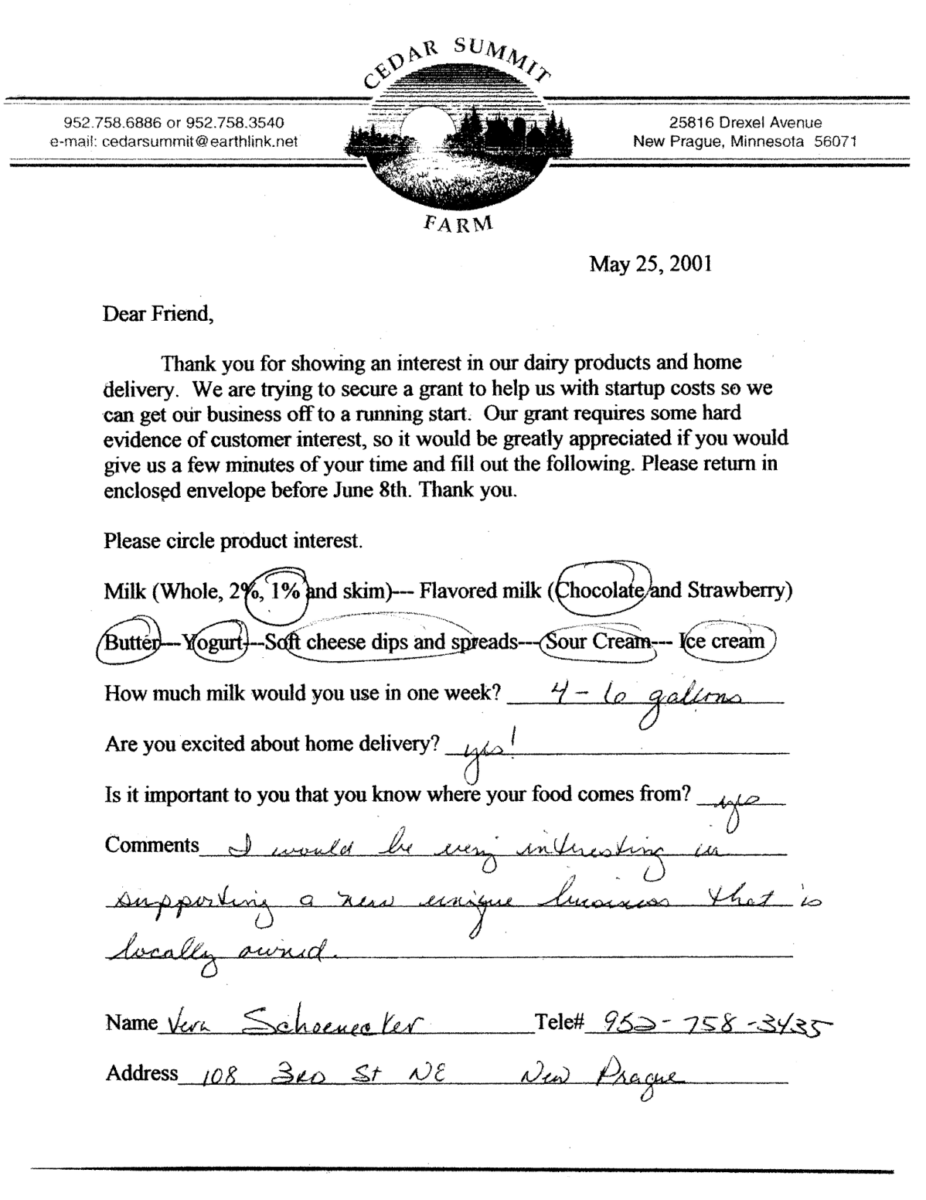

Dave and Florence Minar divided their target market for bottled milk into two major groups by distribution channel, home delivery and retail customers (see Worksheet 4.1). In an effort to learn about their potential home delivery customers, the Minars surveyed 75 New Prague residents about their preferences for flavored milk, weekly milk consumption, and overall interest in home delivery. Based on this research, they developed a customer profile for New Prague home delivery customers.

Like the Minars, begin your target market research by developing a customer profile. Customer profiles can help you determine if a market segment is large enough to be profitable. Break your target market up into segments based on differences in their geographic location, demographic characteristics, social class, personality, buying behavior or benefits sought. Use Worksheet 4.1: Customer Segmentation (download worksheets for task 4) to help you develop and research customer profiles.

Sales potential. If you plan to produce and market a traditional bulk commodity, you won’t have much trouble calculating sales potential. The market for undifferentiated commodities is fluid and can typically absorb all that you produce (albeit at a lower price sometimes). Estimating sales potential becomes more challenging and important when tapping into a specialty commodity market (such as lentils) that may have limited demand, or when your target market is highly sought after and made up of individual households.

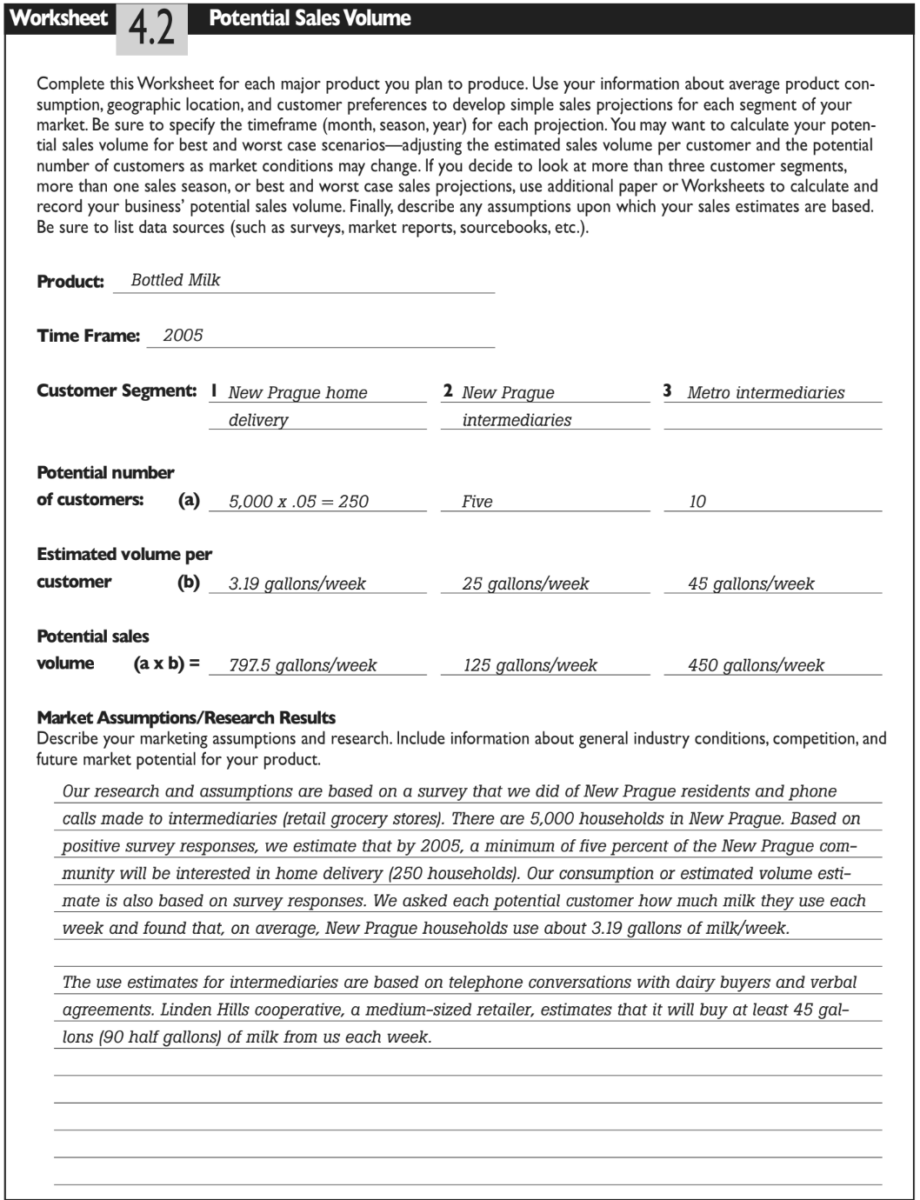

As a specialty commodity producer, your customer (usually another business) will make known how much they are willing to buy short-term (one to two years either through a written contract or verbal agreement. Projecting long-term sales potential may prove more difficult as these markets are usually immature and untested. Similarly, your task of projecting sales potential can be tricky when marketing to individual households. You will need to conduct careful research and be honest with yourself about the market’s growth potential. As mentioned earlier, Dave and Florence Minar of Cedar Summit Farm surveyed their local community about milk usage and demand for home delivery services. From this research, they were able to project sales of up to 798 gallons of home delivered bottle milk per week.

Alternatively, if the Minars did not have the luxury of time or funds to survey their target market, they might develop conservative sales estimates based on the number of households/residents within 25-50 miles of their farm.17 This is how far customers typically travel to purchase something. Cooperative Development Services representative Kevin Edberg says that as a general rule, 75 percent of direct market customers will live within 20 miles of your business.

Using this rule of thumb, Edberg and author Ron Macher suggest a simple way to project direct market sales potential. Begin by locating your farm on a county map and draw 25 and 50 mile radius circles around your farm. Count how many towns or cities fall within the circles. Using this map, add up the number of potential households that live in the nearby cities. These households represent your core potential business customers. Then, with a feel for the number of potential customers, estimate

the potential value of sales per household. This is your sales potential. Begin by estimating the number of customers in each segment and projecting their weekly, monthly or annual purchases. You can develop sales estimates from household or county purchasing records (available at your public library), from your own surveys, in person interviews, or from secondary sources, such as published purchasing pattern data. Excellent sources for consumer demographic and purchasing pattern data are CACI Market System Group Sourcebook, SRDS Lifestyle Market Analyst, and New Strategist Publications’ Household Spending: Who Spends How Much on What. These are available in the reference section of your public library.

Use the space in Worksheet 4.2: Potential Sales Volume (download worksheets for task 4) to begin developing sales estimates for each product that you plan to produce.

Although much of the market research needed for a business plan can begin with your own impressions and a little footwork at the library, you may reach a point where professional help is needed. Many businesses find it useful to hire a marketing consultant to develop proper surveys, lead focus groups, or to conduct telephone interviews. Representatives from your local Extension service or your state Department of Agriculture may be able to assist you in locating qualitative and quantitative information for a customer profile. The Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA), for instance, conducted its own surveys of farmers’ market, u-pick, and Christmas tree farm customers about spending patterns. Survey results are available from MDA’s Minnesota Grown Program. MDA also offers a comprehensive listing of more than 65 regional businesses that buy or process certified organic grains, oilseeds, fruits, vegetables, herbs and maple syrup.

Financial assistance may also be available to help cover some of the costs associated with your marketing research. You should check with your state Department of Agriculture, your local county Extension service (these phone numbers should be listed in your telephone book), as well as the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), to see what programs are available in your area. The USDA Service Center locations give you access to the services and programs provided by the Farm Service Agency, Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the Rural Development agencies. You might also contact the Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) Program in your region to see if they know of any programs available to fund market research for farmers (www.sare.org/). In Minnesota, the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and the Agricultural Utilization and Research Institute (AURI) both provide some financial assistance for marketing research. AURI provides grants to individual business owners and cooperatives for the development of logos, labels and marketing plans.

product: What product will we offer and how is it unique?

Although customer research is the single most important component in building a marketing strategy, it is often the product itself that inspires and excites many business owners. Here’s your chance to develop a thorough product description. Recall that a “product” is any commodity, final consumer good, or service.

As you think about the products your business will offer, try to describe them in terms of the value they will bring to your customers. What is it that customers are actually buying? Dave and Florence Minar described their bottle milk products as “non-homogenized, cream-top milk from grass-fed cows.” In the Minars’ case, customers will be buying old-fashioned taste (non-homogenized milk) and perceived health benefits (associated with milk from grass-fed cows). Moreover, New Prague families will also be purchasing a service: home delivery. This service required research and a pricing strategy just like all of the other products offered by Cedar Summit Farm.

Another way to look at your product is in terms of its uniqueness. What makes your product truly unique? Why would customers prefer your product to another farmer’s? Are there differences in the production process that make it more wholesome and fresh? Can you appeal to the environmentally conscious? Try to look down the road a bit as you profile your product. Will there be new opportunities to add value through processing, packaging, and customer service? How might your product line or services change over time? Use Worksheet 4.3: Product and Uniqueness (download worksheets for task 4) to describe each of the products that you plan to offer, why they are unique, and how they may change in the future.

competition: who are our competitors and how will we position ourselves?

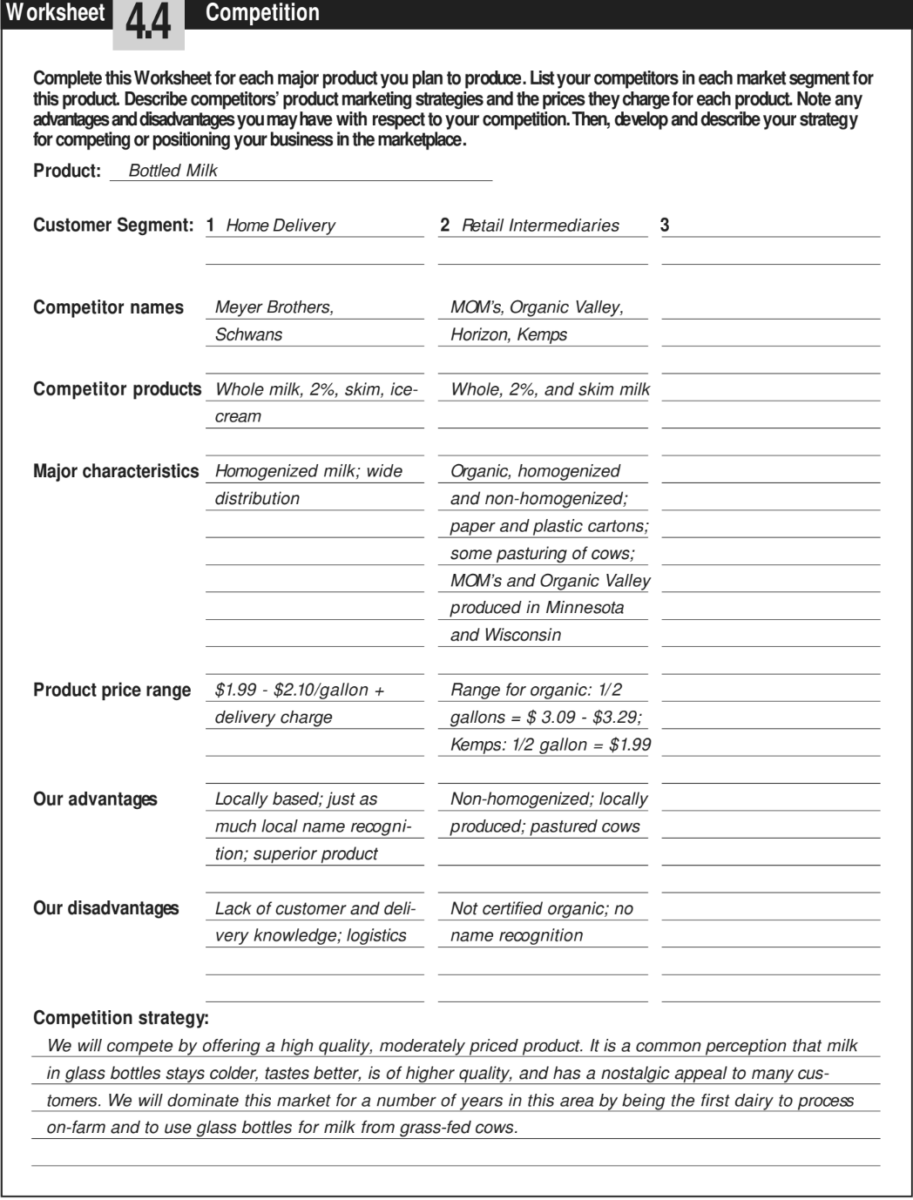

Nearly every business or product has competition of some kind. Find out who your competitors are and what they offer to customers. A trip to the local grocery store, farmers’ market, or even a bit of time on the Internet to research how many growers offer organic asparagus or specialty grains may be all that is needed. Is anyone else serving your target market? If so, find out everything you can about their business or their buyers. You might even consider contacting them. Try to find out how they market and price, and, if possible, get a feeling for their cost structure. You need to determine what share of the market you can realistically capture.

Dave and Florence Minar made phone calls to other home delivery services and visited local retailers when beginning their research. They found that “No farmer in our area is processing and selling his own dairy products. Sources of competition for home-delivered milk into New Prague are Meyer Bros. and Schwans. Meyer Bros. buys milk off the open market and resells it—they do not purchase milk locally or offer non-homogenized products. Schwans will affect us only with ice cream. Some of our competitors in the metro area cooperative groceries are Schroeders, Organic Valley

and MOM’s.”

Use Worksheet 4.4: Competition (download worksheets for task 4) to analyze the competition that exists for each of the products you plan to offer. List your competitors. Then, consider where you have an advantage over them. Can you produce at a lower cost? Do you have access to markets that they cannot reach? Are you better at working with people—at attracting and keeping customers? Do you have better business skills? In other words, what’s your niche? You may want to return to Worksheet 4.3 (Product Uniqueness) where you described your product to ask again, is our product truly unique?

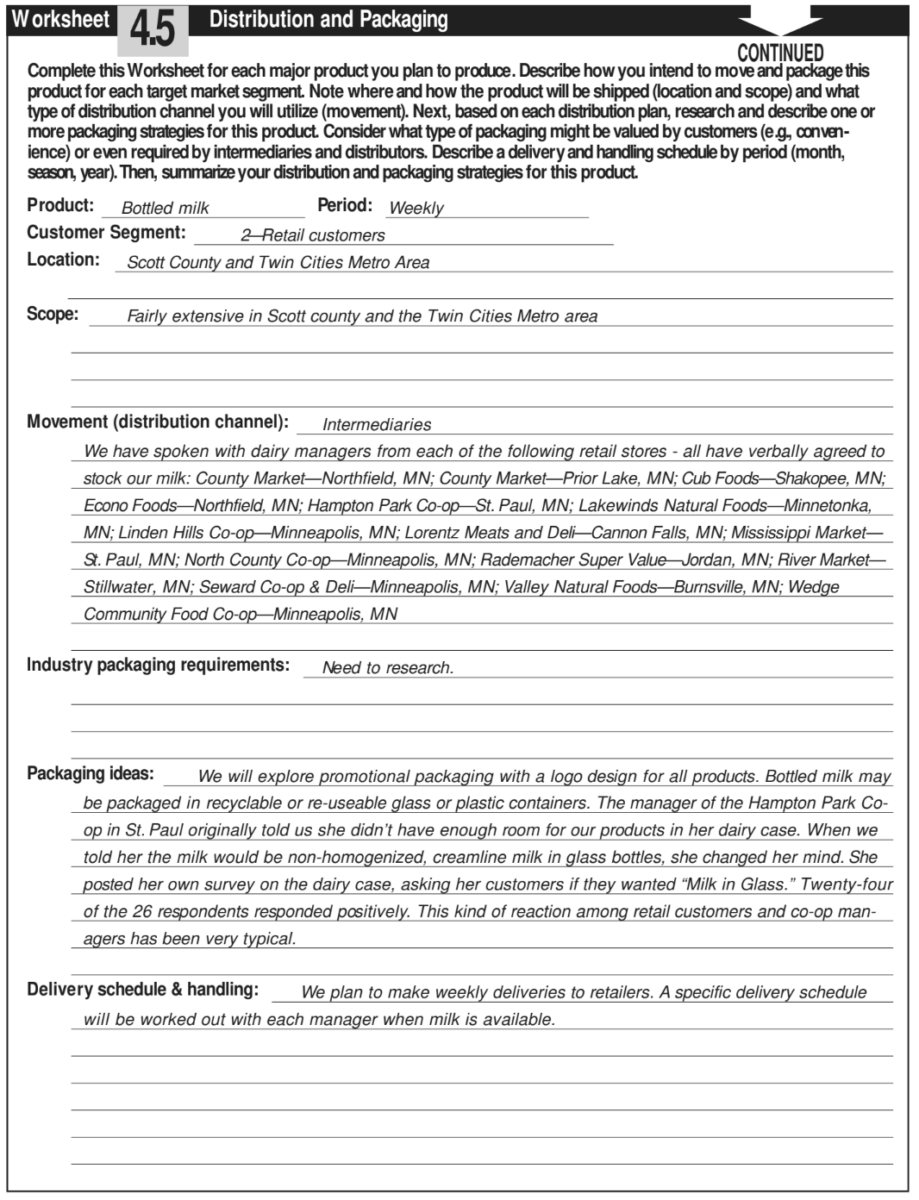

Distribution and packaging: how and when will we move our product to market?

Now that you have a customer and product in mind, your next task is to identify how to move or distribute products from your farm to the customer’s dinner table, store shelves, elevator or barn. Distribution strategies typically describe scope (market reach), movement, packaging and scheduling/handling.

Scope. The first component in your distribution strategy is scope - how widely you plan to distribute your product. Will you pursue an intensive, selective or exclusive distribution strategy?

Intensive product distribution typically involves widespread placement of your product at low prices. Your aim is to saturate the entire market for your goods. This strategy can be expensive and very competitive. Large-scale manufacturers or businesses that market nationwide often employ this method.

Selective product distribution involves selecting a small number of intermediaries, usually retailers, to handle your product. For example, if you plan to produce an upscale product, such as gourmet cheese, you may want to be selective about the stores that stock your product (choosing only those retailers who offer other gourmet, high-quality products). Selective distribution offers the advantages of lower marketing costs and the ability to establish better working relationships with customers and intermediaries.

| District Marketing Distribution Alternatives | Intermediary Distribution Alternatives |

| Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Farmers' markets Home delivery service Internet sales Pick Your Own (PYO) Mail Order Roadside Stands | Retailers Wholesalers Distributors Brokers Cooperatives |

Exclusive distribution is, in effect, an extreme version of selective distribution. In this case, you grant exclusive stocking rights to a wholesaler or retailer. You agree not to sell to another buyer. In exchange, you might demand that the retailer stock only your farm’s salad greens, milk, meat or cheese. You may work closely with a retailer to set market prices, develop promotion strategies, and establish delivery schedules. Exclusive distribution carries promotional advantages, such as the creation of a prestige image for your product, and often involves reduced marketing costs. On the other hand, exclusive distribution may mean that you sacrifice some market share for your product.

Figure 43. Direct Marketing Options

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA)

CSA organizations are similar to a cooperative in that you produce for members. CSA members purchase annual shares of production at the beginning of the year or season. In return, they receive weekly or bi-monthly deliveries of fruits, vegetables, and/or livestock products. CSA projects usually work best close to urban areas. Structures vary and decisions are usually made based on group consensus. You will need good people skills and may have to be creative to keep customers from year to year.

Farmers’ Markets

Farmers’ markets are a relatively low-cost alternative if there is one already operating in your area. You can plug right into an established market (letting it do the promotion for you) and spend most of your energies on production. Typically a full-year or a per market fee is required to reserve stall space at farmers’ markets. The downside is that you will be selling in a very competitive environment and you will not be able to set higher prices.

Mail Order and Internet Sales

Mail order and Internet sales may be a good choice if you are not close to a large urban area and if your product stores and ships well. Perishable and heavy products are not good candidates. These outlets are difficult to get started and work best if you can grow them slowly while relying on other methods for the bulk of your sales. Computerized records or high-quality Web site design are important.

Pick Your Own (PYO)

PYO marketing is a relatively low-cost marketing option. It works best for products in which ripeness is easily recognized. Often you can charge a price that is similar to that for picked produce because the consumer enjoys picking and will pay for the opportunity to do so. Disadvantages include potential damage to the produce, liability concerns, and the fact that a stretch of bad weather can dramatically reduce sales when the product is ripe. Fruit and Christmas trees are traditional examples of PYO enterprises. Fresh flowers are fast becoming a favorite PYO product.

Roadside Stands

Roadside stands require a good location and cheap labor. The most important ingredient to success is attracting repeat customers. Quality, appearance and friendly service are important. Capital requirements can be near nothing if you are in the right location, or they can be substantial if you have to rent space. Check with local authorities for legal requirements and regulations.

Movement. The most common distribution strategies or channels for moving your product to the final customer are direct marketing and intermediary marketing. Examples of each distribution alternative are listed below.

Traditionally, farmers have been positioned at the bottom of the distribution channel — offering a bulk of commodity that required further processing or packaging before it could be sold to customers. Distribution intermediaries, such as brokers and cooperatives, were seen as the only option for moving products from their farm to the final customer. However, a growing number of farmers today are doing their own processing, packaging and delivery. This adds value to their raw product and helps them to retain raw product and helps them to retain a greater share of the profit. As a result, farmers have expanded their distribution strategies to include direct marketing— selling consumer goods such as goat cheese, bundled fruit trees, or bottled milk directly to the final customer.

In filling out Worksheet 4.5: Distribution and Packaging, (download worksheets for task 4) the Minars identified two general distribution strategies for their dairy products: direct marketing (via farmers’ markets and home delivery), and intermediary sales (via traditional grocers and natural foods cooperatives). As they continued the planning process, the Minars focused their research and evaluation on the two distribution strategies with the most potential for reaching each of their market segments: home delivery to New Prague households and sales to Twin Cities Metro and New Prague retailers.

If you choose to direct market, consider the options listed in Figure 43. Think about the investment required, marketing and labor costs, pricing options, grower liability, and barriers to entry.

Service providers also distribute directly to customers. In this case, it might be from an office, via fax, or on site at the customer’s home or business.

While direct sales can be a profitable strategy for the individual grower, they generally make up only a small portion of total sales and can be costly in terms of time. You often take on wholesaler responsibilities such as grading and packing when direct marketing. The majority of consumer goods reach grocery stores or restaurants through some type of intermediary. Intermediaries are businesses that help buy, sell, assemble, store, display and promote your products; they can help you move your product through the distribution channel. Intermediaries include retailers, wholesalers, distributors, brokers and cooperatives. The advantages and disadvantages of distributing through well-known intermediaries are briefly described below.

If your distribution strategy includes sales to retailers or wholesalers, you will need to conduct substantial research. A recent study by the Center for Integrated Agricultural Systems indicated that Minnesota and Wisconsin retailers are very interested in purchasing and stocking local produce. However, they are often unwilling to do so because of inconsistent product quality. “Consistent quality means a predictable product for customers. . . When it comes to quality, many buyers want it all—produce that is shaped and sized consistently and of uniform ripeness and flavor; something they can get from California growers.” The study also identified six basic tips for approaching or selling to retail buyers, listed in Figure 45.

Figure 45. Recommendations for Approaching Retail Buyer

Become knowledgable about the market by talking with farmers selling to retail stores. Try to find out individual buyers’ expectations of volumes and prices to see if they match your situation before approaching the buyer.

Prepare an availability sheet listing products and prices. Make it neat and well-organized. Make sure there will be enough produce available to back up what is listed.

Send the availability sheet to buyer whose expectations best match what you have to offer. Buyers often prefer to see this sheet before they talk to a producer. You can fix it to the buyers office.

Project a professional image through a growers' manager or representative. This person should be well-informed about production, supply, produce condition, and be confident in the business' ability to meet the buyers' needs.

Work out the details of the sale with the buyer, such as volume, size, price, delivery dates and labeling requirements. Some buyers have a set of written requirements for growers.

Keep in touch with the buyer. Growers need to keep the buyer informed about potential problems so that buyers can look elsewhere for a product if there is a supply problem.

Similarly, wholesale outlets can be difficult to access. Many of the same retail marketing principles apply to the wholesale market. You will need to concentrate as much management on grading and packing as on production. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, you will need to prove to your buyer that you are a dependable and consistent source of high-quality product.

If one of your distribution alternatives includes the wholesale market, you may want to begin your research by contacting local grocers and restaurants to find out who supplies their produce and other food products. Lakewinds Natural Foods in Minnesota, for instance, purchases approximately 90 percent of its food items from regional wholesale distributors such as the Wedge’s Cooperative Partners Warehouse, Roots and Fruits Cooperative Produce, Blooming Prairie Natural Foods, and Metro Produce.24 Next, contact the wholesaler. Find out their grading, packaging and delivery requirements. If they seem like a good fit—and if the prices they offer are financially acceptable—try selling yourself to them.

There are a number of resources available to help you identify and reach intermediaries. One of the best resources is the Cooperative Grocer On-line. This site offers links to retailers, such as cooperative grocers, as well as other intermediaries, such as manufacturing cooperatives, wholesalers and distributors.

Packaging. Product or service packaging can be both functional and promotional—serving to preserve your product for shipment and, in the case of final consumer goods, to advertise and differentiate your product.

As a producer of bulk commodities, your packaging strategy may seem fairly straightforward since little or no packaging may be involved. However, if you are planning to produce specialty commodities, such as organic grains, be aware that strict industry “packaging” standards may exist.

Packaging final consumer goods for the retail market, on the other hand, can be a daunting yet exciting task. Examples of product packaging include individual product cartons, boxes and containers; bulk shipping containers; delivery vehicles; and even retail display cases for mass product packaging.

Service packaging examples include business cards, invoices, landscaping, building design, signage, brochures and vehicles.

As a producer of consumer products, you may want to begin your research at the supermarket or grocery store. Make note of how similar products are packaged and labeled. There are many rules and regulations governing food packaging and labeling. In general, any product packaged for the retail market must include a description of the common product name, net weight, nutrition facts, ingredients and your business address. All products must meet federal regulations. However, you should also contact your state’s food inspection department for more details, since state guidelines may be stricter than federal guidelines. [In Minnesota, see the MDA’s Food Labeling Fact Sheet. The Agricultural Utilization Research Institute (AURI) also provides technical assistance for the development of nutrition labels (see “Resources”, p. 249)].

Finally, as a service provider, think about what your customers will see, hear and smell when visiting your farm or communicating with you and your staff. Northwind Nursery and Orchard owner Frank Foltz laid out the following plan for “packaging” the service component of his business:

“The sales room for nursery stock and fruit will be decorated with a country theme and include locally crafted items useful for gardening, orcharding and homesteading purposes. We will avoid all but the very highest quality products. Staff will be friendly and knowledgeable in all aspects of fruit growing and orcharding. The property will be developed in a free-flowing, park-like fashion with an interspersion of fruit trees and edible landscaping plants that will elevate our customers from the simple act of buying fruit or nursery stock to that of experiencing our natural environment at its best. This arboretum-type setting will provide customers with the opportunity to take a ‘fruit walk’ to sample many different fruit cultivars in season and subsequently purchase more fruit, or the nursery stock to grow their own.”

As you think about what type of packaging is best suited to your product, don’t overlook customer needs, such as convenience, and intermediary requirements. Restaurant owners and cooperative grocery managers will likely have minimal packaging requirements that affect how you clean, bundle and grade your product. Lakewinds Natural Foods General Manager Kris Nelson says produce farmers, in particular, must compete with major distributors and therefore deliver a professionally packaged product. “Kale and other greens come to us from farmers already cleaned and bundled,” Nelson says. “They are dropped off at the store in packaging that is similar to what we see from commercial distributors.” 25 If you plan to market to retailers and other intermediaries, research their packaging requirements and think realistically about your ability to meet industry standards.

Your values and goals, as well as target market preferences, will also affect packaging choices. The Minars, for instance, envisioned marketing to customers “who value old-fashioned taste.” As a result, one of their distribution strategies was to package their milk in old-fashioned, returnable, glass bottles. “It is a common perception that milk in glass bottles stays colder, tastes better, is of higher quality, and has a nostalgic appeal to many customers,” they say in their business plan. By packaging in glass bottles, the Minars were also able to satisfy one of their environmental values—namely, to minimize their impact on the land through reuseable packaging.

Delivery scheduling and handling.

Your distribution strategy should also take into account how often you will need to make deliveries, either to satisfy customer demand or to fill intermediary requirements. What type of delivery schedule will be necessary? If you offer a perishable product, delivery schedules will be critical. The Minars spoke with retailers to research delivery conditions, such as the handling of returnable bottles, and a delivery schedule. Moreover, if you are marketing through an intermediary, your ability to meet delivery commitments may determine their continued business. “Retail buyers rely on delivery at the promised time so they know how much may need to be supplemented to meet demand and so they can schedule workers to handle delivery and display.” As you develop a delivery schedule, be aware of peak production periods (if your business is seasonal) as well as industry handling requirements. Organic producers are required, in most cases, to verify that organic grains were handled (cleaned, stored and transported) in accordance with organic standards.

Use Worksheet 4.5: Distribution and Packaging (download worksheets for task 4) to develop and describe your overall distribution strategy or strategies. The decisions you make here will affect your future workload and consequently, your human resources strategy.

Pricing: how will we price our product?

Farmers are all too familiar with the challenges of pricing bulk commodities for profit. As price takers, low market prices are often the number one reason traditional commodity producers find themselves sitting down to develop a business plan. Today’s producers, whether they are adding value or marketing a specialty commodity, have a greater ability to influence price in these highly defined markets. Depending on your goals, vision, target market, and product strategy, you may want to consider one or more pricing strategies for undifferentiated (traditional) commodities and differentiated (value-added, specialty) products.

In general, pricing strategies are based on two factors: prevailing market prices and your costs. In the long run, your price has to cover your full costs—including production, marketing and promotion—as well as a return for your time and investment. You will have the opportunity to crunch these numbers later when you evaluate the strategy you are currently developing.

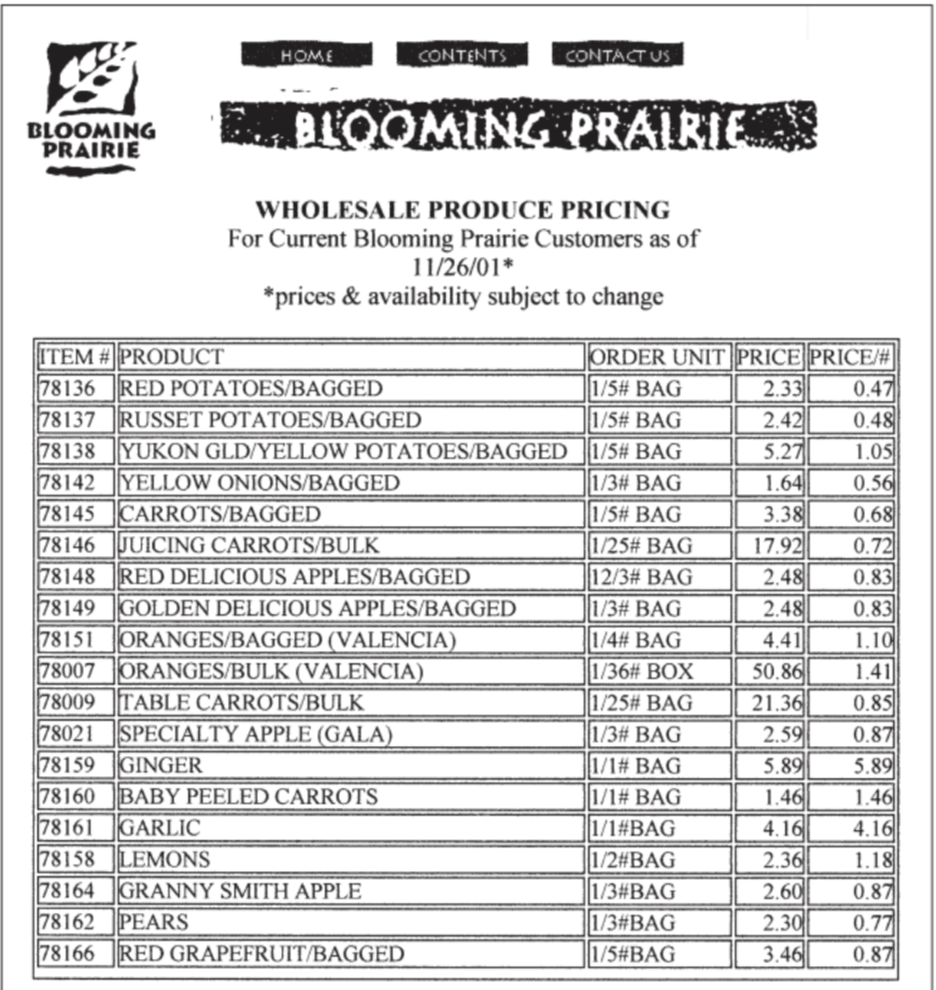

For now, begin developing a pricing strategy around prevailing market prices for similar products if they exist. Learn about what customers are willing to pay and what prices your competitors charge. Begin your research by listing competitor prices for similar products—note any seasonal pricing changes, premiums and discounts offered by intermediaries (brokers, grain companies, processors, retail groceries, etc.). Check with your state Department of Agriculture, or your University Extension Service for a list of current market prices for traditional commodities, such as livestock and forages. Specialty commodity prices may be difficult to locate or only available for a fairly substantial fee. Markets for organics, non-GMOs, and other specialty commodities, such as lentils, are relatively immature and little information is available. Therefore, you will have to do a little digging when searching for historic, current, and projected market prices. In general, a good source for alternative product prices, including organics, is the Internet. Food cooperatives, like Blooming Prairie, list weekly wholesale prices for produce. Retail prices for a range of processed dairy and grain products, fresh produce, flowers, herbs and spices often are available on individual company Web sites. Moreover, the Appropriate Technology Transfer for Rural Areas (ATTRA) has compiled a listing of relatively low-cost organic market price and industry research called Resources for Organic Marketing (see “Resources”). If you have Internet access or are willing to make a few phone calls, your market price research needn’t take long.

Once you are familiar with prevailing market prices and your costs of production, you are ready to begin developing a pricing strategy. There are a variety of strategies to consider depending on your ability to set prices. Common pricing strategies for differentiated (value-added or specialty) commodities including consumer goods and services (with relatively high price setting ability) are discussed in Figure 48.

If you are a small or mid-sized producer selling in a local market, be careful not to place too much emphasis on price competition. You will likely have better results competing based on quality, value added and communications. Still, you need to think about how to price your commodity or product.

One common product pricing approach, skim pricing, is to establish a relatively high market entry price to recover costs before lowering the price to expand the customer base. This practice, however, can attract more competition if your prices remain too high for too long. The alternative is penetration pricing. Similar to promotional pricing, you initially set a product price below your intended long-term price to secure market acceptance of your product. The advantage of penetration pricing is that it will not attract competition. When selecting a pricing strategy for differentiated commodities, products or services, take a peek at the options listed in Figure 48.

Figure 48.

Differentiated Product Pricing Strategies

Competitive pricing. Competitive pricing strategies are common among large manufacturers and are aimed at undermining competition. Predatory pricing, where a company sets its price below cost to force its competitors out of the market, is a typical competitive pricing strategy. Although these strategies may work well for large commercial companies, they are not recommended for small scale, independent businesses. Price wars are not easily won. That said, the food industry is considered a “mature” marketplace and your ability to compete on the basis of price may be very important. There are several well-capitalized players, even in the organic market, offering similar services.

Cost-oriented pricing. The cost-oriented pricing strategy is probably the most straightforward. Based on your production costs, you and your planning team make a subjective decision about whether to price your product at 10 percent, 50 percent, or 100 percent above current costs. Of course, you will need to conduct marketing research to determine whether or not your customers are willing to pay the cost-plus price that you have established.

Flexible or variable pricing. Flexible pricing strategies involve setting a range of prices for your product. Flexible pricing is common when individual bargaining takes place. The prices that you set may vary according to the individual buyer, time of year, or time of day. For instance, farmers who sell perishable fruits, vegetables and herbs at farmers’ markets often establish one price for their products in early morning and by day-end are willing to lower their prices to move any excess product.

Penetration or promotional pricing. A penetration pricing strategy involves initially setting your product price below your intended long-term price to help penetrate the market. The advantage of penetration pricing is that it will not attract competition. Before pursuing a penetration pricing strategy, you should thoroughly research prevailing market prices and crunch some numbers to determine just how long you can sustain a below-cost penetration price. Penetration or promotional pricing usually takes place at the retail level when marketing direct to your product’s final consumers.

Product line pricing. If you plan to market a line of products, you might consider a product line pricing strategy where a limited range of prices is established for all of the products that you will offer. For instance, if you envision marketing to low-income customers, then your price line or price range must be based on “affordability.” In this case, you might establish an upper limit or ceiling for prices so that your price line is bounded by your production costs on one end and an affordable ceiling on the other end.

Relative pricing. Relative pricing strategies involve setting your price above, below or at the prevailing market price. Clearly, this strategy requires that you research the prevailing market price for your product.

Skimming or skim pricing. The price skimming strategy is based on the idea that you can set a high market entry price to recover costs quickly (to “skim the cream off the top”) before lowering your price to what you intend as the long-term price. This pricing strategy is possible only when you have few or no competitors. The primary disadvantage of the skimming strategy is that it attracts competition. Once competitors enter the market, you may be forced to match their lower prices.

Contract pricing for specialty commodities. Contracts for specialty commodities vary dramatically in terms of the price paid, payment conditions, grower responsibilities, storage and shipping arrangements. The advantage of pricing on contract is that you know in advance what price will be paid for the commodity. Be aware, however, that when producing a specialty variety crop or when employing a new production management system, your yield and output risk increases as does your exposure to quality discounts. Use a contract checklist if you are considering this method of pricing for specialty crops or livestock.

Common pricing strategies for undifferentiated (raw) commodities (with low price setting ability) are discussed in Figure 49. Traditional commodity pricing strategies also have their advantages and disadvantages as described in Figure 49. When considering each of the commodity pricing strategies, remember that there are many factors that can affect your overall market price strategy, such as storage capacity, cash flow and taxes. Whatever type of pricing strategy you choose, think through your rationale. Are you trying to undermine the competition by offering a lower price? Set a high price that reflects your quality image or market demand as is the present case with organic products? Are you simply looking to cover costs and reduce volatility?

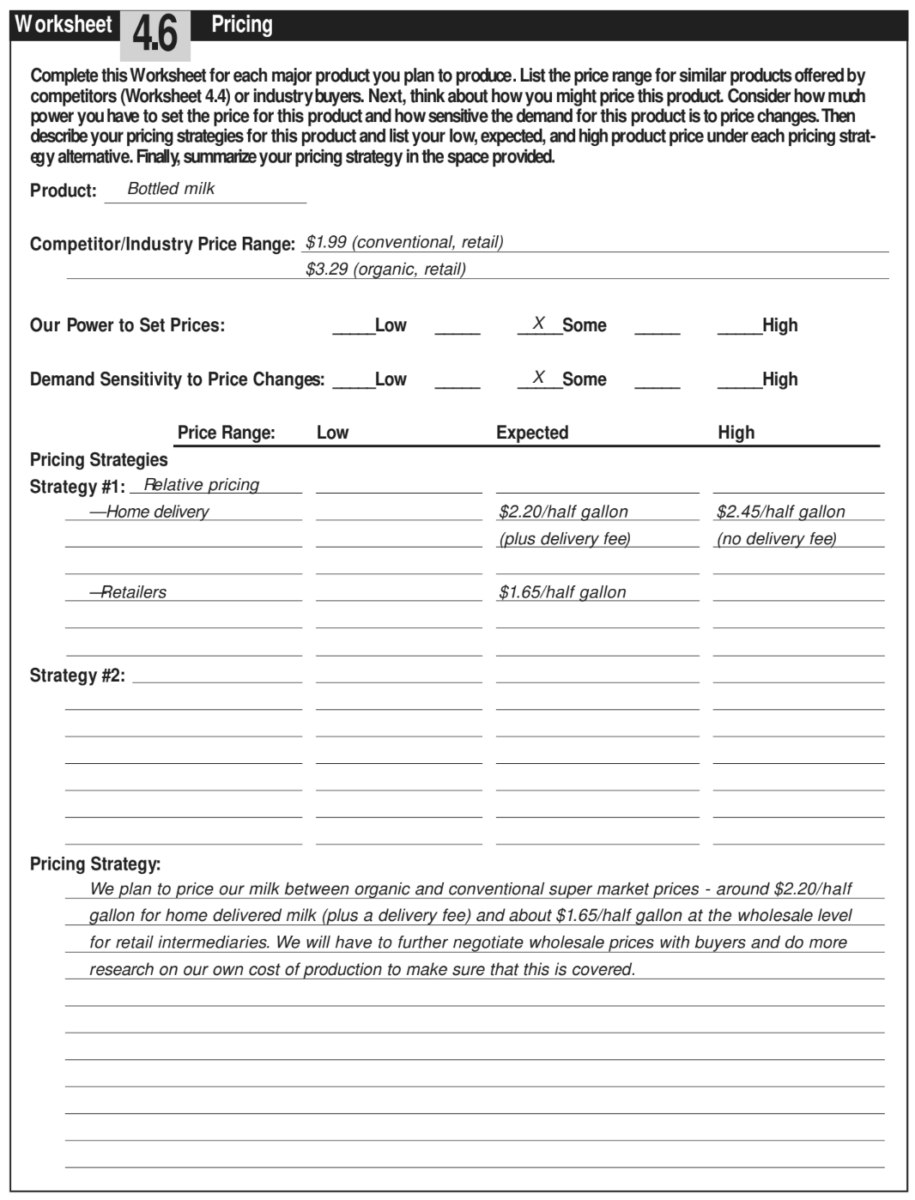

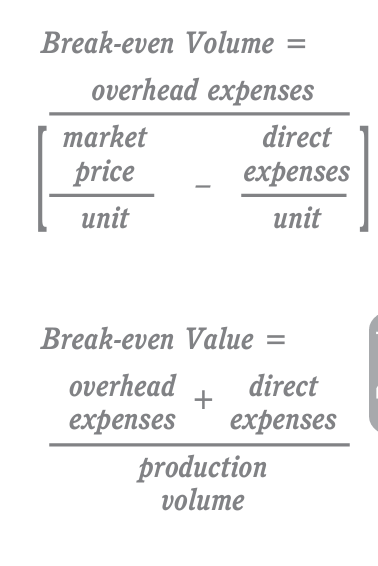

The Minars identified two pricing strategies for bottled milk (relative and cost-based pricing) to help place their product in retail and wholesale markets. By introducing new customers to Cedar Summit Creamery’s “old fashioned” bottled milk at a price well below that of organic milk, the Minars hoped to encourage quality and health conscious shoppers to try their product. The Minars’ break-even analysis in the evaluation step of this Planning Task helped them determine whether or not a relative or cost-oriented pricing strategy would be financially feasible.

Use Worksheet 4.6: Pricing (download worksheets for task 4) to develop your pricing strategy for each product. Begin by recording research about competitor’s prices.

Figure 51.

Common Pricing Mistakes

Marketing author Michael O’Donnell outlines the following common “mistakes” to be aware of when building a market price strategy.

- Pricing too high relative to customers’ existing value perceptions; prices not in line with target market needs, desires or ability to pay.

- Failing to adjust prices from one area to another based upon fluctuating costs and the customer’s willingness and ability to pay from one market to another.

- Attempting to compete on price alone

- Failing to test different price levels on customers, from one area or market to another

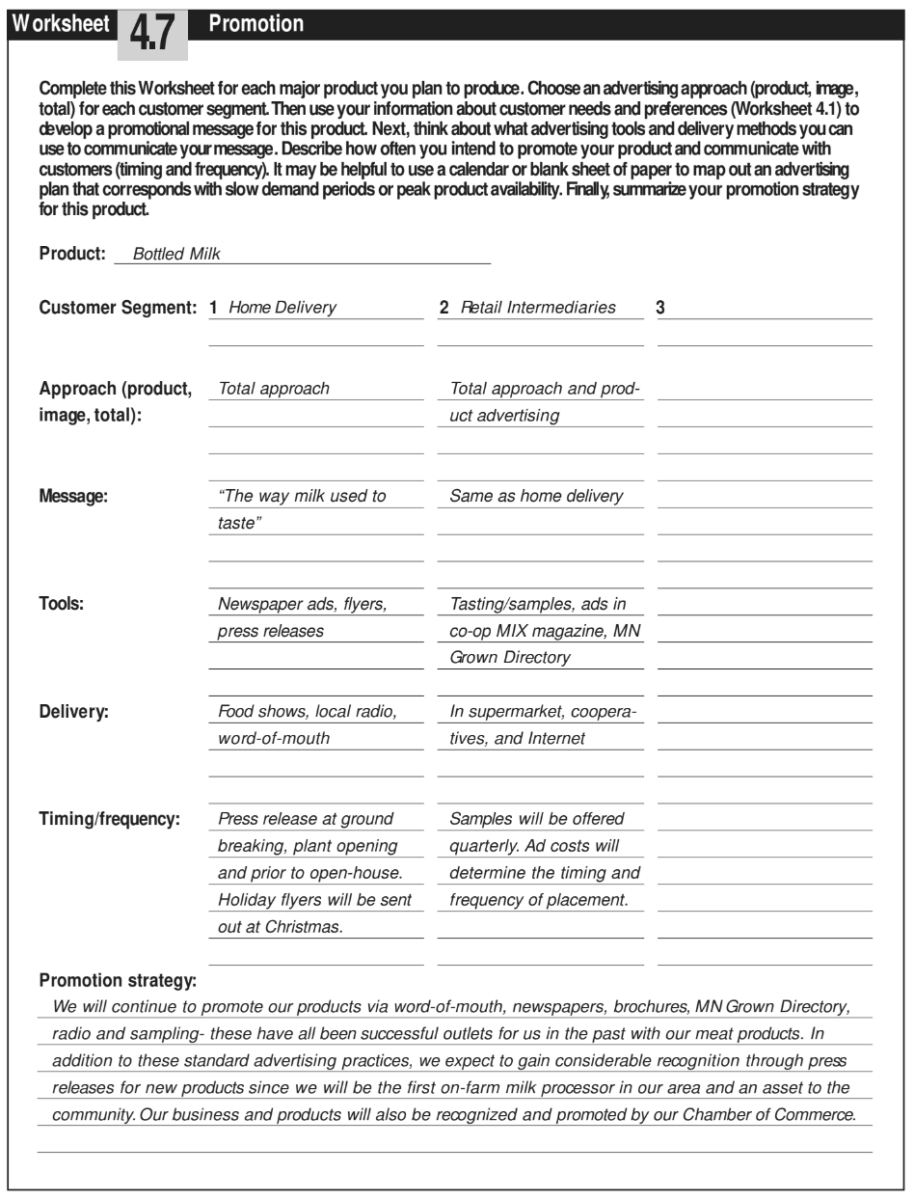

promotion: How and what will we communicate to our buyers or customers?

Promotion is a must if you are going to gain product recognition among customers. Promotional strategies often are built around a “message.” The message that you deliver about your product or business is just as important as the product itself. Equally important is how and when you deliver that message through the use of advertising tools and media.

Image or product. Before beginning detailed promotions research, think about an overall strategy approach. Will you concentrate promotions on your business image, the product, or both (total approach)?

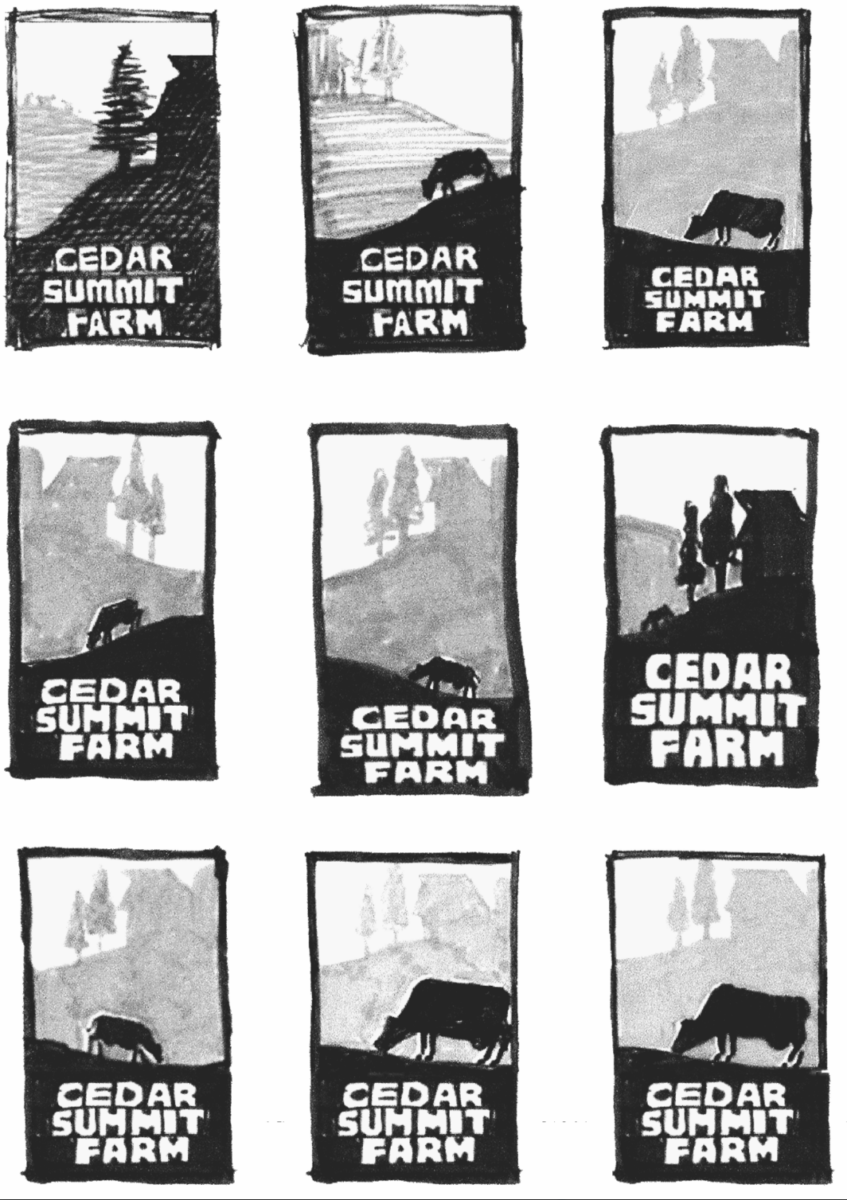

Businesses use brand or image advertising to build awareness and interest in their products. A brand is represented by a name, term, sign, symbol, design or some combination. A brand or logo is used to identify the products of your business and to distinguish them from other competitors. Although the establishment of a brand can be expensive, particularly for small businesses, many of today’s alternative farm businesses are concentrating their promotional efforts on image advertising—promoting the concept of “healthy” or “locally produced” or “eco-friendly” products.

The Minars plan to promote Cedar Summit Farm products through the use of a new label and logo design that will appear on all products and in their brochure. They hired a family artist to develop a variety of logos that would communicate their overriding values and new business mission statement.

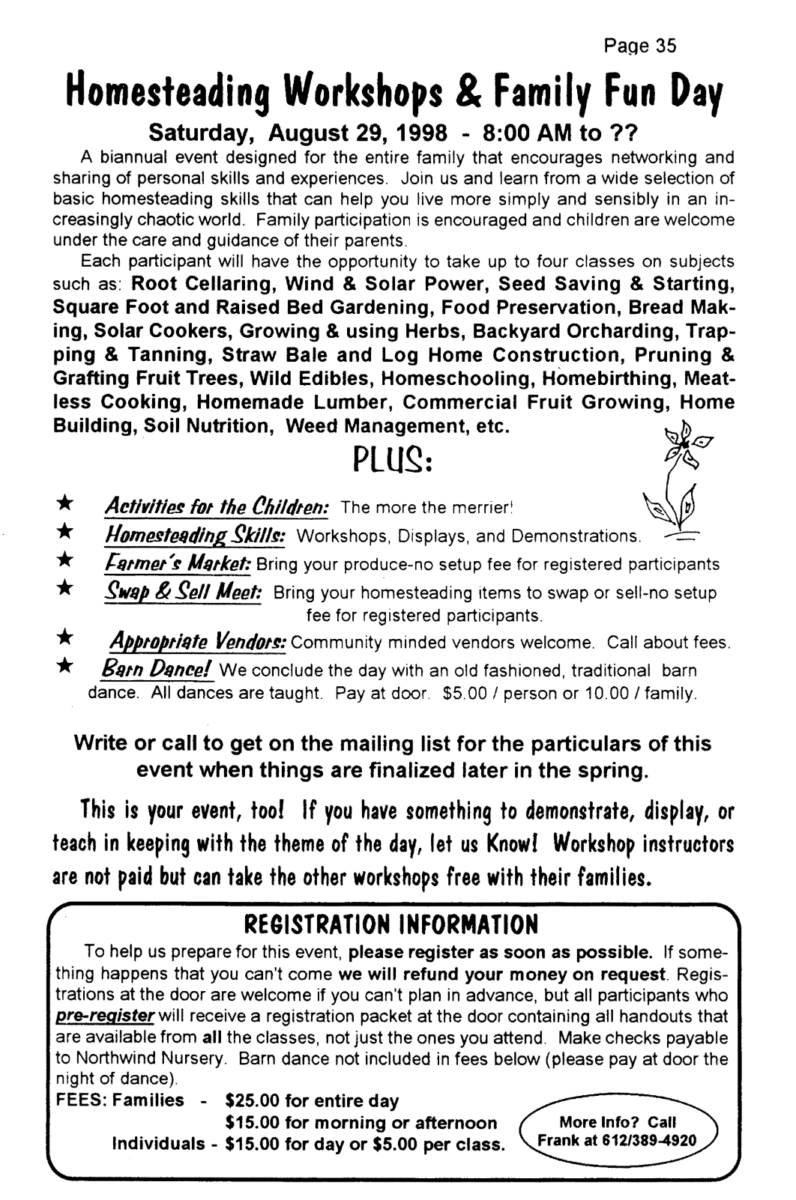

Product advertising aims to create immediate sales through some type of special product offer, such as seasonal discounts, frequent buyer clubs, and in-store samples. For instance, Northwind Nursery and Orchard owner Frank Foltz developed a three-pronged product strategy to: “(1) Make use of excess products by distributing them as advertising samples—we will give it to customers who can use it. They will repay us many times over in ‘word of mouth’ advertising; (2) Give our customer discounts for bringing in other customers or distributing our literature, etc. . . . Give those who organize group orders a bonus; and (3) Reward loyal customers with extra services that will help them succeed.”

Promotion Strategy

Your promotion strategy should include a promotional method, specific promotional tools, and your ideas for actual promotion or delivery.

Message: What do I want my customers to know about my product?

Tools and Delivery: What will I use to communicate my message?

Timing and Frequency: How often will I contact my customers via advertising and communications?

Costs: How much will my advertising and communication cost?

Product promotion aims to increase sales directly and immediately for an advertised product. Here are several low-cost product promotion alternatives.

- Coupons and rebates

- Tasting and cooking demonstrations

- Frequent buyer clubs

- Publicity

- Samples

- Recipes

While most small businesses opt for product advertising because it offers more immediate returns, marketing consultant Barbara Findlay Schenck recommends combining both image and product promotion strategies. She calls this promotional strategy total approach advertising. Total approach advertising offers direct farm marketers a chance to build a long-term image of their business and its values while encouraging timely product purchases.

Dancing Winds Farm owner Mary Doerr, for example, promotes the image of her business with flyers that read “Dancing Winds Farm is a small farm enterprise using sustainable agriculture practices” as well as her business’ product by offering free cheese samples and recipes at the St. Paul Farmers’ market every other weekend.

Use Worksheet 4.7: Promotion (download worksheets for task 4) to describe your general promotions strategy. Next, with a broad strategy approach in mind, begin sketching out the particulars of your advertising message, tools, delivery and schedule.

Message. Advertising messages can be fun, serious, or factual. They can describe business values, the product itself, production practices, prices, or the volume available for sale.

If you intend to use a product promotion strategy, your message can describe the unique characteristics of your product or a special offer. On the other hand, if your

strategy is centered on image promotion, your message should paint a clear picture of what you want your business to be known for among customers. Return to your Business Mission Statement (Worksheet 3.2), in which you first answered this

question; it is a good place to start formulating your promotional message. Either way, if you plan to produce a retail product, try to keep your messages short so that it can be incorporated into product packaging.

Take a look at the following image and product-related messages advertised by several well-known Midwest retail food suppliers:

“Our organic products are not only good for the earth, but for you and your family too! Together we can change the world—one organic acre at a time” —Horizon Organic

“Bob’s Red Mill is dedicated to the manufacturing of natural foods in the

natural way . . . We stone grind all common and most uncommon grains into

flours and meals on our one-hundred-year-old mills . . . Our product line of natural

whole grain foods [is]the most complete in the industry” —Bob’s Red Mill

“Applegate Farms is working to improve the meat Americans eat . . . All of our products are gluten-free, contain low or no carbohydrates, are lower in fat than other major brands and free of all taste or texture enhancers” —Applegate Farms

Research other business messages online, in advertisements, or at the grocery store.

Tools and delivery. Frank Foltz, owner of Northwind Nursery and Orchards, promotes his business’ products using a range of promotional tools, including fact sheets that are distributed at farmers’ markets and educational on-farm displays. “Quality products and knowledgeable, personal service along with a series of informative fact sheets on fruit growing culture and problems are an integral part of our catalog sales strategy,” says Frank. “Those, along with on-farm learning opportunities, community activities and cultural events are the back-bone of our local promotions efforts.”

The Foltzes’ experience suggests that educational fact sheets are one of the best ways to reach their target market customer—individuals interested in learning more about backyard orcharding and edible landscaping.

Promotion or advertising tools typically include display ads, billboards, yellow pages, mailings, flyers and catalogues. Your state Department of

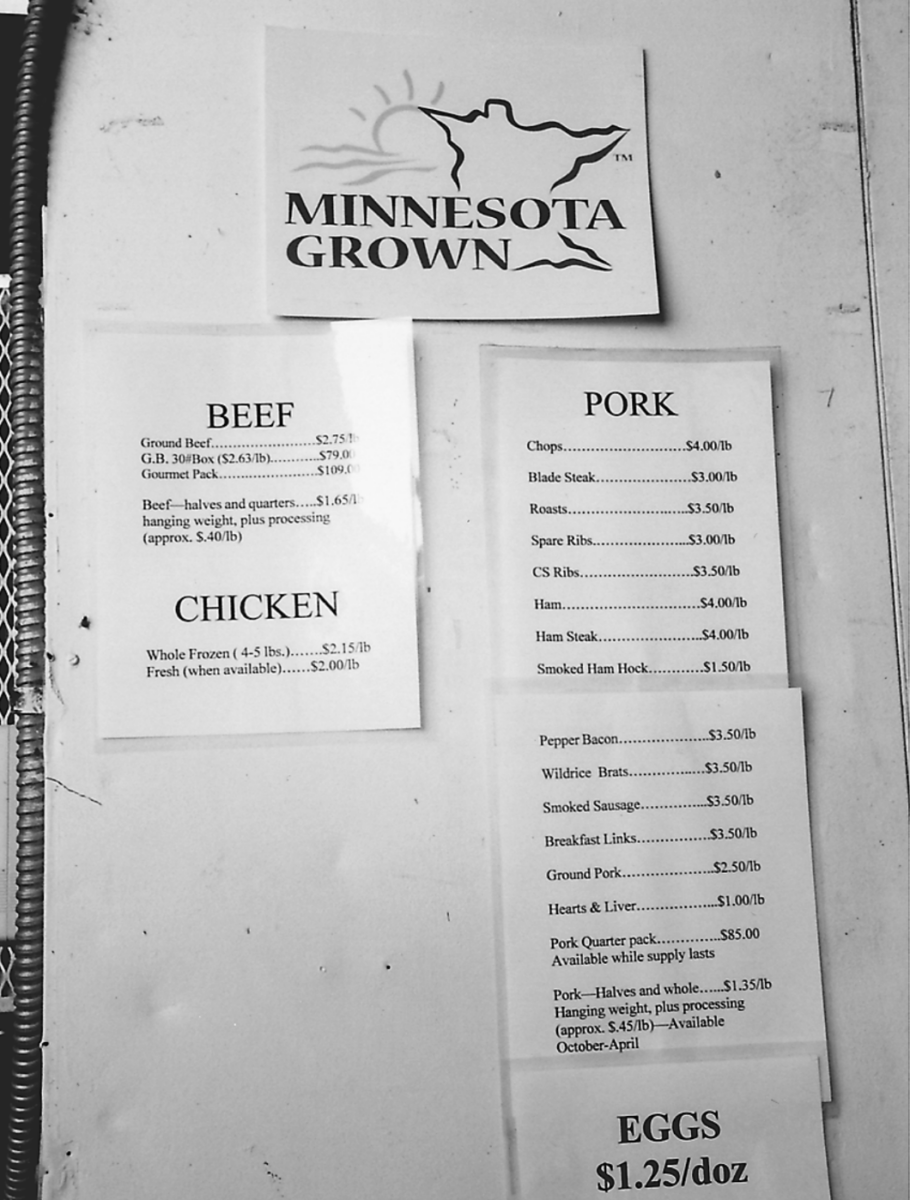

Agriculture likely has a program promoting locally grown products. The Minnesota Grown Directory is an excellent advertising resource for farmers in Minnesota and Wisconsin who have seasonal and year-round products to sell. Minnesota Grown program participants, like the Minars, are listed in an annual directory and receive permission to use the trademarked Minnesota Grown logo.

Every advertising tool has its advantages and disadvantages. Think about which tools will help you best reach your target market. Once you’ve developed a list of potential advertising tools, think about where you will deliver or distribute your promotional message. Trade shows, farmers’ markets, county fairs, radio, television, and the Internet are just a few promotional delivery options. Be sure to brainstorm with your planning team. Identify creative, low-cost, effective ways to get the word out. You might consider a word-of-mouth campaign or a strategic alliance with another farmer.

Mary Doerr of Dancing Winds Farm linked up with a nearby Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) business owner to offer “cheese shares” in its CSA brochure. The Minars negotiated a verbal agreement with a meat producer in West Central Minnesota to market Cedar Summit Farm milk products to that producer’s existing direct market customers. That agreement would allow the Minars to promote their milk products beyond South Central Minnesota and gradually increase the size of their target market.

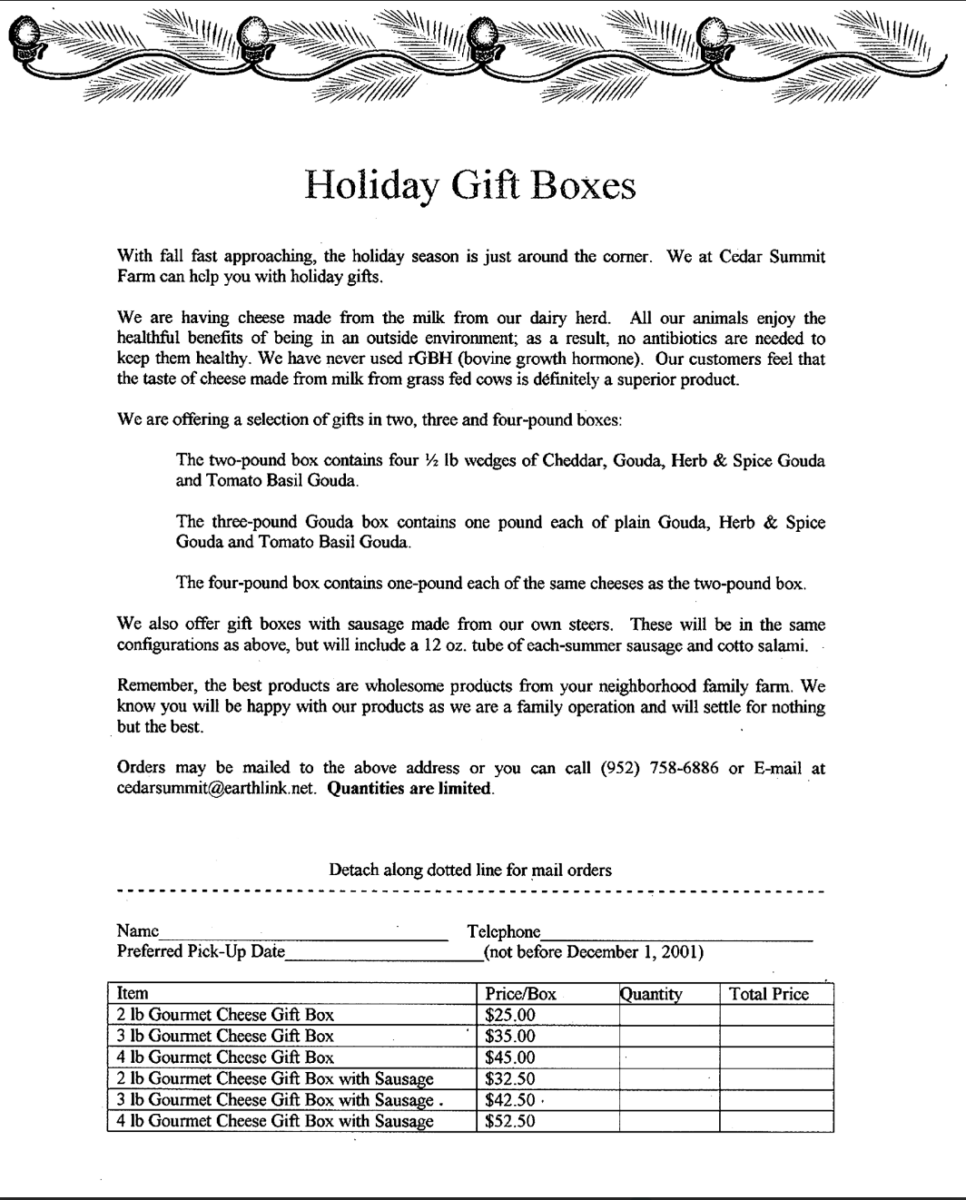

Timing and frequency. Promotional strategies should include a plan for timed delivery or an advertising schedule that describes how often you will communicate with customers to follow- up on a sale, inform them of holiday specials (see Figure 56), or let them know about new products and prices. Regular communication is a way to build and preserve your market.

Frank Foltz of Northwind Nursery and Orchards maintains regular contact with customers by informing them about new orchard research and varieties. How will you advertise and maintain contact with your customers? Through regular personal contact, periodic promotional mailings, or a holiday mailer? It may be helpful to develop a calendar for promotional “events” to help time promotions with seasonal demand or peak production periods. This will also help you plan for advertising expense outlays when developing your cash flow plan as you evaluate your proposed strategy later in this Planning Task.

A series of interviews with Minnesota and Wisconsin retail buyers found that farmers who communicated regularly with buyers regarding deliveries and product availability were more successful at maintaining these customers. When communicating with intermediaries, it is a good idea to appoint a single representative to deal with the buyers so that a personal relationship can be built. This person should be knowledgeable about your business’ products and able to negotiate with buyers.

Your communication strategy might also incorporate feedback elements to obtain information from customers. Frank Foltz describes this strategy

approach best in his business plan: “We will treat our customers as an extension of our research and development departments. Their problems and complaints about our products can help us eliminate future production problems and their suggestions may be as helpful as any hired consultant. We will listen attentively to their concerns, dealing with problems immediately and always give the customer the benefit of the doubt.”

Regardless of the promotional strategy you pursue, you and your planning team will need to be creative to catch the attention of your customers and stretch your advertising dollars. Promotion, though seemingly overwhelming, should be fun.

Return to Worksheet 4.7: Promotion (download worksheets for task 4) to sketch a promotional strategy and advertising plan for each of your products. Think about your values and goals as well as your target market, product and potential competition. Like the Minars, be sure to detail your overall promotional strategy, message, advertising tools, delivery ideas and communication plans.

inventory and storage management: How will we store inventory and maintain product quality?

Storage and inventory management are integral and important parts any business strategy, affecting product quality, marketing opportunities, and the business’ legal standing. While this may seem to be more of an operations issue, many marketing strategies may depend on whether or how long you can store your product.

What role will inventory and storage management play in your business? Like traditional grain producers who use storage as a way to mitigate seasonal price declines, Riverbend Farm owner Greg Reynolds devoted a substantial portion of his operations research toward the development of a low-cost storage system for organic vegetables. He sought to preserve his produce and prolong his marketing season.

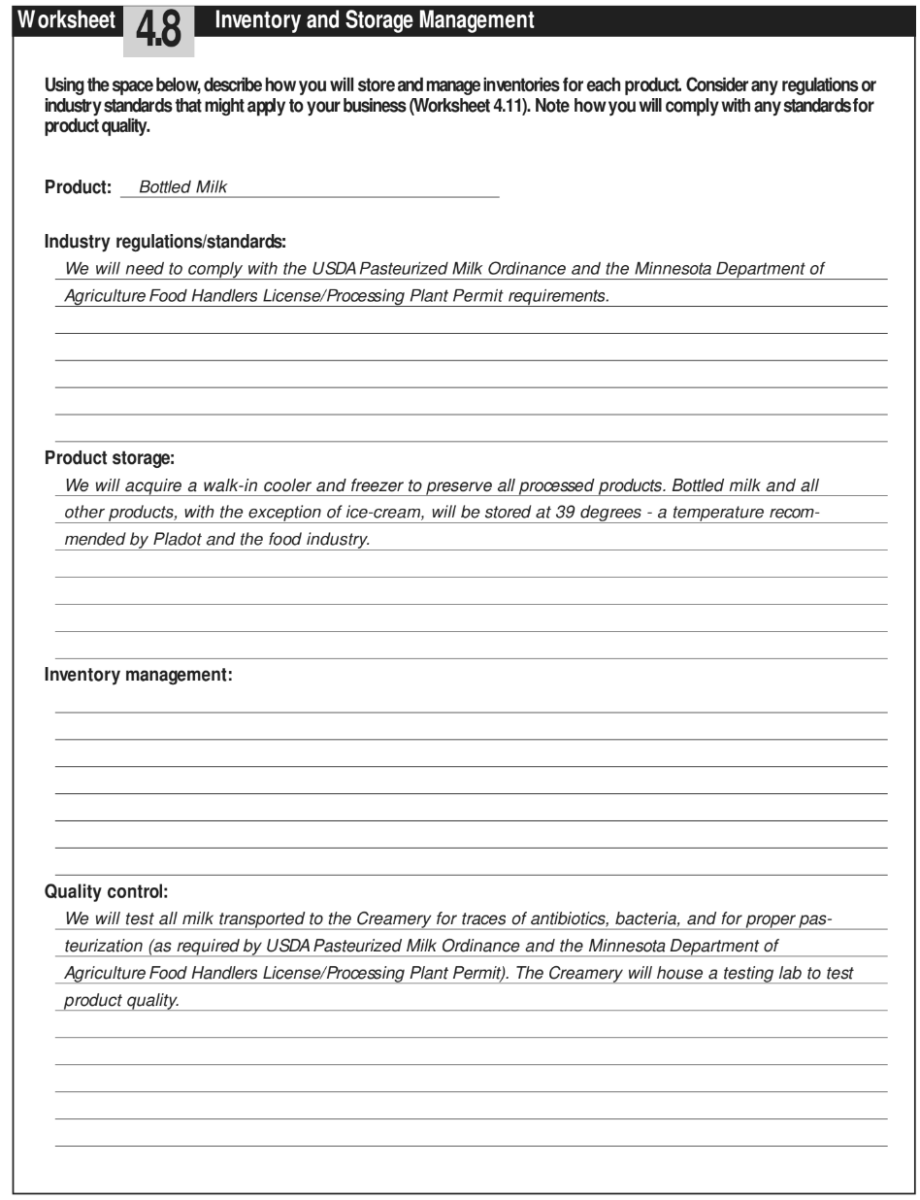

You might shape your storage strategy around marketing or to satisfy regulatory considerations. Certified organic producers, for example, must maintain detailed storage and harvest records in order to market their crops. Similarly, in accordance with the USDA Pasteurized Milk Ordinance and the Minnesota Department of Agriculture Food Handlers License/Processing Plant Permit, the Minars are required to test all milk transported to Cedar Summit Creamery for traces of antibiotics, bacteria and proper pasteurization once it has undergone this process. According to Worksheet 4.8, Cedar Summit Creamery will house a testing lab and storage cooler on-site to assure the quality of milk and preserve bottled milk, cheese, sour cream, butter and ice-cream products.

Think about your storage and inventory management objectives, then research your options and use Worksheet 4.8: Storage and Inventory (download worksheets for task 4) to describe this piece of your marketing strategy.

Develop a Strategic Marketing Plan.

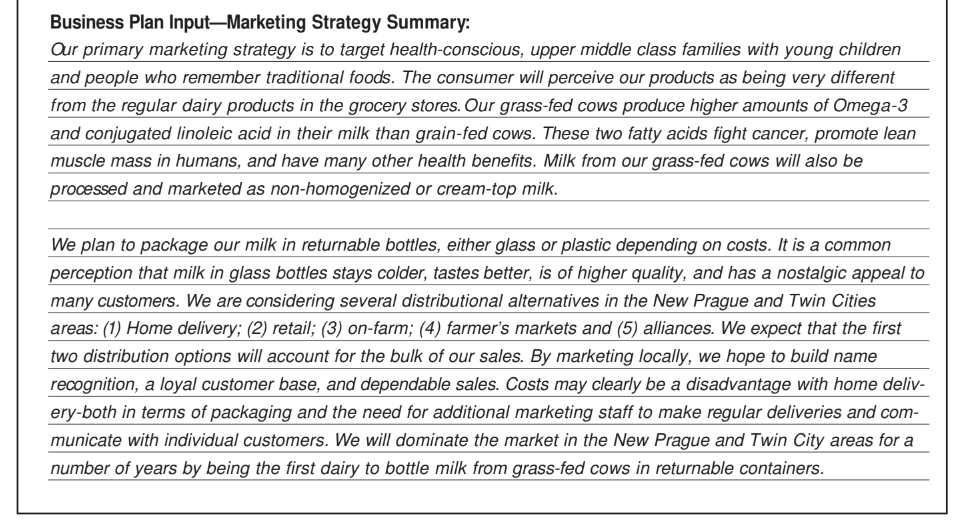

Think about how all of your individual product marketing ideas (product, distribution, pricing and promotion) can fit together into one or more general marketing strategies for the whole farm. Use Worksheet 4.9: Marketing Strategy Summary (download worksheets for task 4)to summarize your marketing research and strategies for each product and to note how these strategies and external conditions (such as competition) may change throughout your transition or start-up period. Then think about how individual product strategies fit together into one, whole-farm marketing plan. This is the time to refine your initial product strategies if necessary to incorporate new information.

The Minars completed the Marketing Strategy Summary Worksheet 4.9 for each product in their proposed cream-top product line. An excerpt from their Worksheet for bottled milk—in which they identified several pricing, distribution and packaging strategy alternative —is shown above. Note that they still had a lot of details to work out, such as expenses associated with glass versus plastic milk cartons and the economic feasibility of on-farm sales and collaborative marketing efforts. But the beginnings of a very strong marketing plan were in place.

If you haven’t already done so, take time now to complete Worksheets 4.1—4.8 for each product that you plan to market. Refine your target market, if necessary, based on your research. Do this together with your planning team. Next, using Worksheet 4.9: Marketing Strategy Summary, briefly describe your distribution, packaging, pricing, and promotion strategies for each product and begin gathering expense estimates. Then summarize your product strategies into a whole farm strategic plan. Note any strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) associated with each general marketing plan, listing supporting evidence from your research.

Operations Strategy

With a clear idea of who will buy your product and why, the next planning question you must answer is: How will we produce it? A detailed operations strategy—one that is clear to all involved in the operation—is necessaryfor sound management and is sometimes an institutional necessity. Organic producers, for example, are required to submit a detailed farm management plan when seeking certification each year. According to certification guidelines, the plan must describe all resource management strategies directed at improving soil fertility; controlling weeds, pests and disease; managing manure; and limiting erosion.

In this section you will have the chance to develop a production management and operations strategy by answering questions about:

- Production Management: What production/management alternatives will we

consider? How will we produce? - Regulation and Policy: What institutional requirements exist?

- Resource Needs: What are our future physical resource needs?

- Gaps: How will we fill physical resource gaps?

- Size and capacity: How much can we produce?

- Storage and Inventory Management: How will we store inventory and maintain product quality?

production and management: How will we produce?

All operations strategies begin with a detailed description of the business’ production (management) system and a production schedule. As a current producer, you may have very clear ideas about how you would like to produce, what management system to use and resource requirements. If so, this portion of the planning process may be a welcome break from the research that was necessary to learn about your customers and competition in the previous section. If you

are a beginning farmer, however, you may find that this component of the planning process is just as research-intensive. Take your time, and, most importantly, talk with other experienced farmers when fleshing out the details of your production system and production schedule.

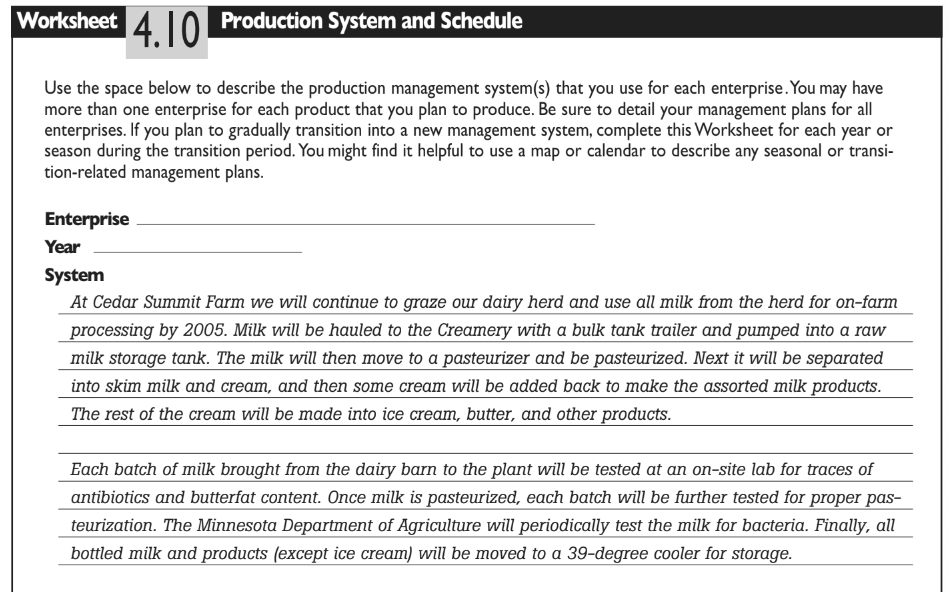

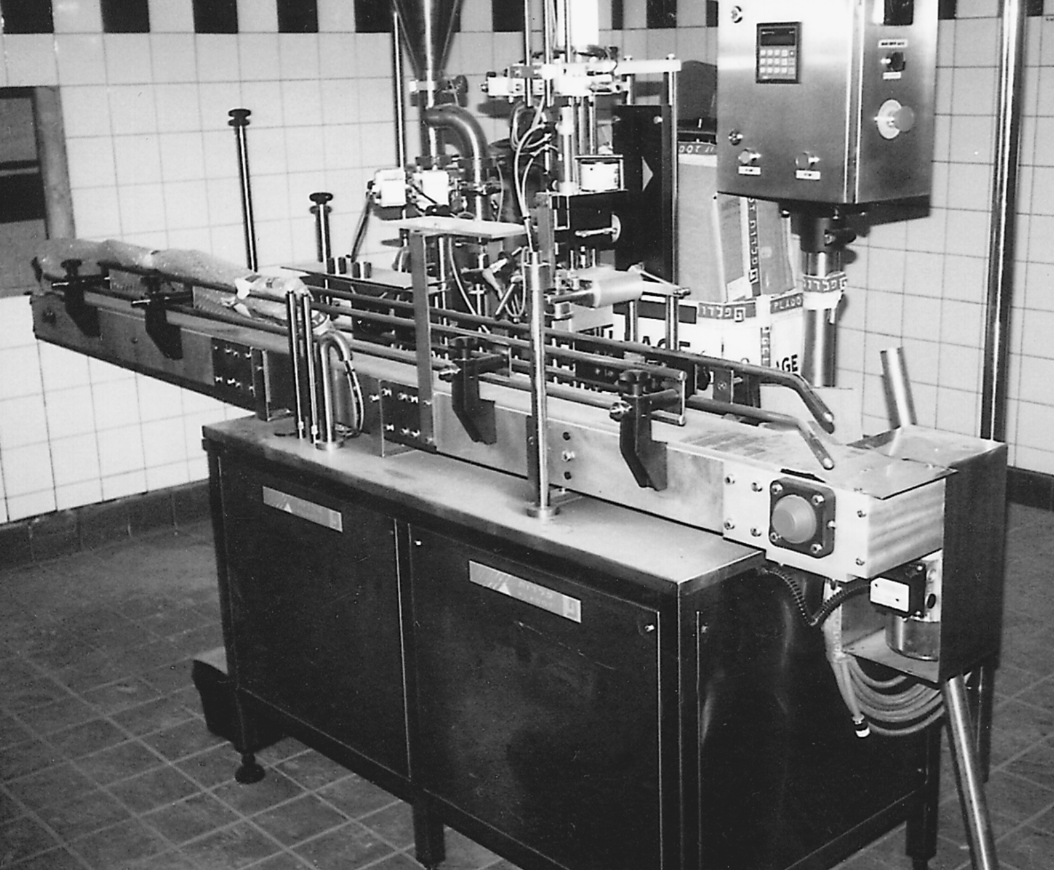

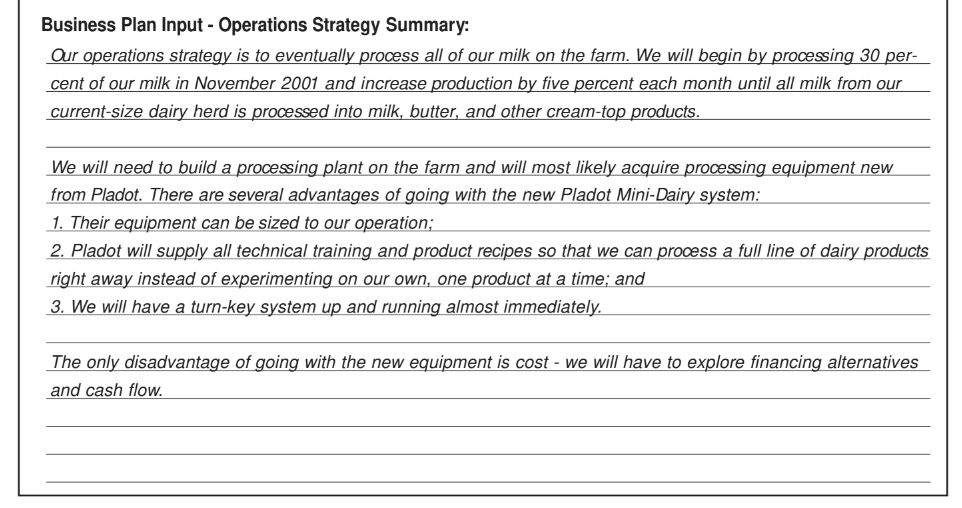

Production system. Before making their decision to process, the Minars traveled thousands of miles to Maryland, Virginia and West Virginia to visit four other farmer-owned milk processing plants. Each of the plants was similar in size to the Minars’ proposed operation. They processed with “Mini- Dairy” equipment from an Israeli-based company called Pladot. By visiting the plants, observing production, and talking first-hand with plant owners, Dave and Florence feel they gained invaluable insights that helped them with decisions about plant construction, equipment purchases and marketing.

Your choice of production system will be heavily influenced by your social, environmental and community values. This might be a good time to revisit your values and goals, and to recall your objectives for the whole farm. Each production system carries with it different resource requirements, production outcomes, labor demands and natural resource implications.

As you define one or more production system strategies, try to be specific

about how the system will work on your farm. If your vision includes a major

change in production, think about the resource requirements and the trade- offs between labor, productivity, conservation and profitability that may be associated with different production management systems. Use the space in Worksheet 4.10: Production System and Schedule (download worksheets for task 4) to describe your production system strategies for each farm enterprise. If you plan to produce crops or livestock, for instance, detail your plans for: weed, pest and disease control, soil fertility, rotation, tillage, irrigation, water quality, seed selection, breed selection, fencing, feed, housing, stocking, and waste and quality control

Similarly, if you plan to process or offer a service, the systems component of your plan might address your business’ strategy for workshops or on-farm consultations. Northwind Nursery and Orchard owner Frank Foltz, for instance, took time to describe his operation management plans for farm tours and pruning demonstrations.

There are many resources that describe traditional and, increasingly, alternative production systems. Most universities have published research studies on reduced input, organic and livestock grazing systems. Two excellent publications are the Grazing Systems Planning Guide and Making the Transition to Sustainable Farming. Most importantly, talk with other farmers—learn from their mistakes and their successes.

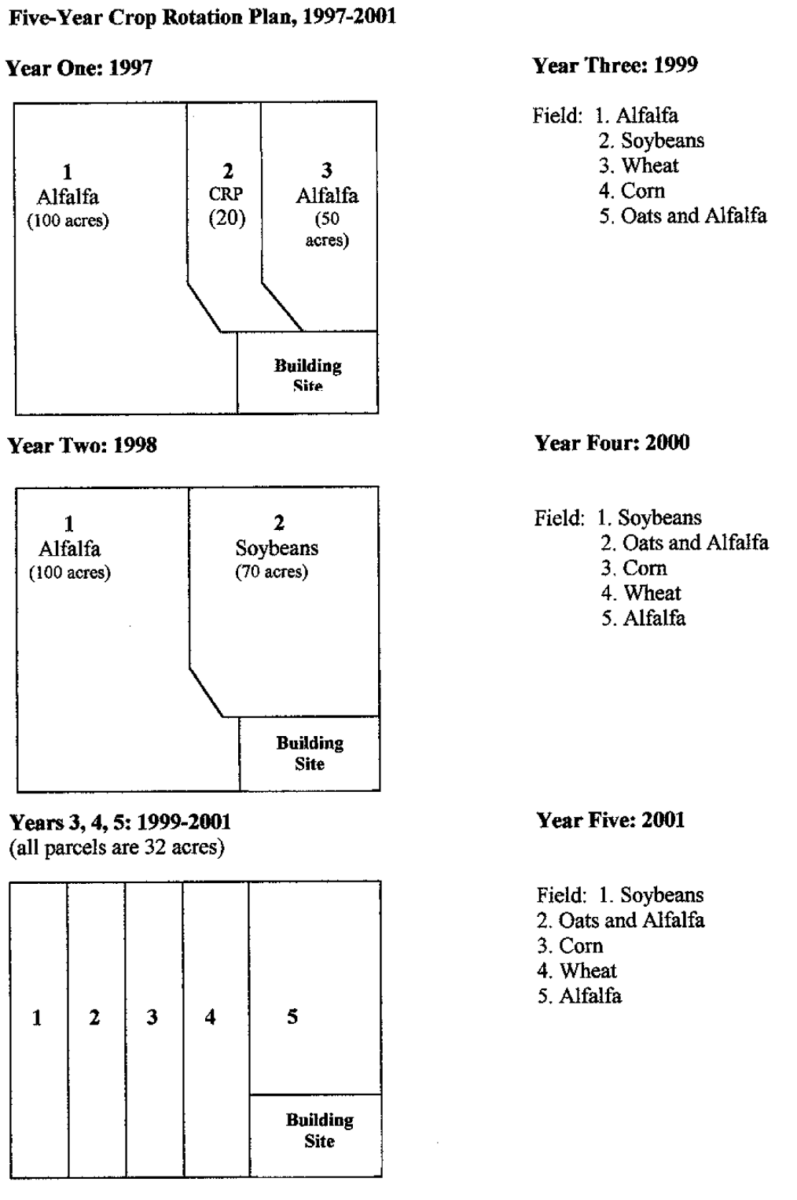

Production schedule. Once you have identified one or more production system strategies, think about how management within each system may change over time (e.g., from season to season or from year to year. For instance, how might your livestock management change as you transition from a system of confined farrowing to pasture farrowing for hogs, or from summer grazing to winter feeding for cattle if you plan to seasonally graze? Similarly, think about your annual crop rotation schedule, weekly vegetable harvesting schedule, or daily farm tour schedule. This type of detailed operations planning is critical for any business—it can help you estimate physical and labor resource needs and production potential, as well as cash flow projections. And in many cases, detailed production schedules may be necessary for institutional compliance. Crop producer Mabel Brelje, for example, is required to submit a crop rotation plan annually in order to obtain organic certification. For this reason, she included a rotation map in her final business plan (Figure 60).

Figure 61.

Permits Required by Cedar Summit Farm to Build Plant and Process

- Conditional Use Permit from Scott County Planning and Zoning

- Septic Tank Permit from Scott County Environmental Health

- Health and Safety Plan Approval from the Minnesota Department of Health

- Building Permit and Inspection from the Scott County Building and Inspections Division

- Environmental Operating Permit from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency

- Food Handlers’ License from the

Minnesota Department of Agriculture - Dairy Plant License from the Minnesota is Department of Agriculture

Similarly, Dave and Florence Minar included a proposed processing schedule in their final business plan to communicate financial needs and performance to their lender:

“We plan to process and sell 30 percent of the milk produced on our farm the first year. Processing will then be increased by five percent each month until May 2004 when all of our milk will be processed.” The Minars also developed a detailed product processing schedule for each batch of bottled milk, yogurt, sour cream, butter and ice cream that was not included in their business plan. It served as an internal guide for operations.

Use Worksheet 4.10: Production System and Schedule (download worksheets for task 4) to describe your operations schedule. If you plan to make a gradual transition over time, either from one system to another or through the addition of new enterprises, use Worksheet 4.10 to map out a short-term production plan and descriptions for each phase of the transition. Use a map, a calendar or the space provided. Discuss your schedule with experienced farmers, planning team members, and consultants to determine if your production system and overall schedule are realistic.

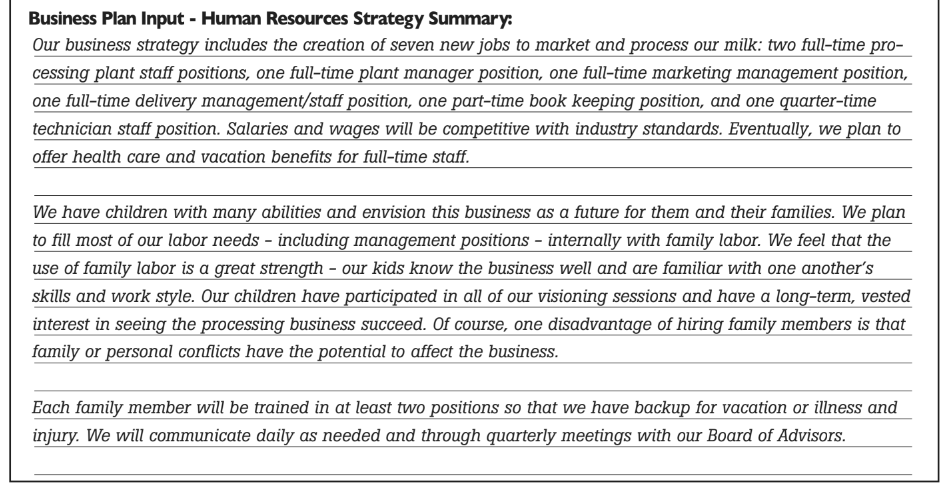

regulations and policy: What institutional requirements exist

Like it or not, if you are going to operate a retail business, process on your farm, or greatly expand livestock production, you will run into local zoning, permitting, licensing and regulatory issues. Regulations can have a major impact on your production and operations plans as well as on start-up costs. Dave and Florence Minar, for example, had to obtain seven permits to build a plant and process their own milk (Figure 61). The type of permits or licenses required for your business will depend on where you are in the business life-cycle (whether you are just starting up or growing your business), where you live, what type of product you offer, and the overall size of your operation. Therefore, before going too far with your operations research, it’s a good idea to check with your state’s Small Business Association as well as your local or county regulators to learn about environmental, construction, finance, bonding and product safety regulations. In Minnesota, A Guide to Starting a Business in Minnesota 38 lists all necessary state permits and licenses as well as informational contacts. Some examples of the agriculture-related licenses and permits required by the State of Minnesota are listed in Figure 62.

Figure 62.

Some Agricultural Licenses and Permits Required by the State of Minnesota

- Aquaculture License

- Apiary Certificate of

Inspection - Farmstead Cheese Permit

- Dairy Plant License

- Grade A Milk Production

Permit - Feedlot Permit

- Retail and Wholesale Food

Handler License - Livestock Meat Processing

and Packing License

Moreover, if you plan to produce, process or market organic crops, you will

need to conduct thorough research about national and international certification

requirements. You should contact your state Department of Agriculture for

information about the new federal organic certification program.

Use Worksheet 4.11: Regulations and Policies (download worksheets for task 4) to begin your research, listing required permits and licenses, filing requirements, and fees. Next, determine whether or not you will be able to meet legal requirements. Discuss your ideas with planning team members and outside consultants, such as an attorney, when appropriate.

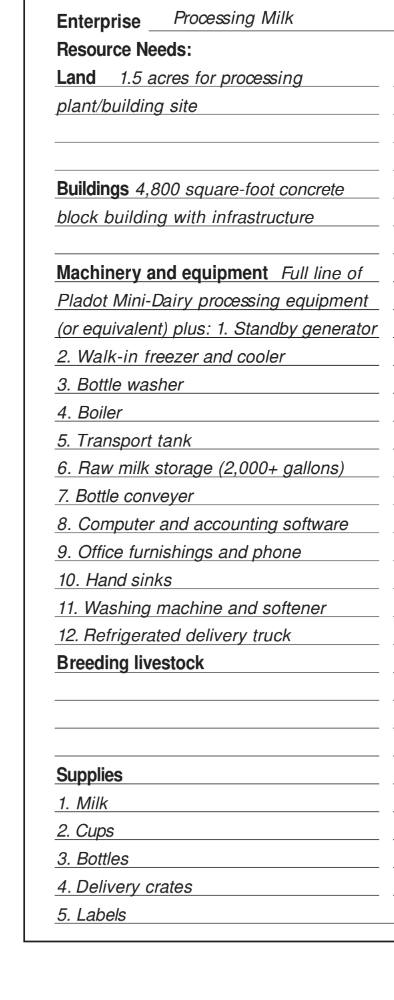

resource Needs: what are our physical resource needs?

Traditional resource management plans address land, labor and capital. Here you will identify needs in all of these areas, but limit your strategy development to land, buildings, breeding livestock, equipment and variable inputs or supplies. Labor-related strategies are discussed separately in the Human Resources Strategy section.

Take stock of your operation’s future resource needs for each enterprise and ultimately, the whole farm. Think about how much land you will need, what type of equipment you will use, and any other physical inputs necessary to produce your product. The choices that you make regarding resource use, acquisition and ownership can have a big impact on the overall profitability of your business. The costs of owning and operating farm machinery in Minnesota, for example, account for 20 to 30 percent of the annual per acre production costs for corn and soybeans.

If you are new to the business or industry and uncertain about resource requirements, try talking with experienced producers or your local Extension educator to begin brainstorming a realistic list of land, livestock, machinery, equipment, labor and other input needs. If you plan to produce a specialty commodity or use an alternative management system, accurate production input records may not be readily available. In this case, your research may take you to the Internet or some of the alternative experiment stations located at universities across the country. Your regional SARE office (see “Resources”) may be able to help you locate information sources in your area.

If you are new to the business or industry and uncertain about resource requirements, try talking with experienced producers or your local Extension educator to begin brainstorming a realistic list of land, livestock, machinery, equipment, labor and other input needs. If you plan to produce a specialty commodity or use an alternative management system, accurate production input records may not be readily available. In this case, your research may take you to the Internet or some of he alternative experiment stations located at universities across the country. Your regional SARE office (see “Resources”) may be able to help you locate information sources in your area.

Dave and Florence Minar developed a list of processing resource needs by visiting other on-farm dairy processing plants and from business plans shared by these same business operators. Using this information, the Minars were able to generate a fairly detailed list of needed machinery, equipment and start-up inputs (Figure 63).

Referring to your completed Worksheets 2.5 and 2.6, use Worksheet 4.12: Describing Potential Crop Production Systems and Worksheet 4.13: Describing Potential Livestock Production Systems to record future resource needs for crop and livestock enterprises, respectively. Think about how your operating schedule and corresponding resource needs will change as you transition into a new management system over a period of seasons or years.

resource gaps: how will we fill physical resource gaps?

Another critical component of your operations strategy involves your plan for filling resource gaps. Return to your crop and livestock production schedules (Worksheets 2.5 and 2.6) from Planning Task Two in which you described current crop and livestock input needs and equipment use. Compare these lists to those that you completed for future operations (Worksheets 4.12 and 4.13). Are there any gaps? Or perhaps you now have underutilized resources?

Consider some of your strategy alternatives for filling or eliminating gaps between current land, building, machinery and equipment availability and future physical resource needs. Will you:

- Make better use of existing machinery and equipment?

- Acquire additional (new or used) resources?

- Gain access to additional resources through business arrangements

(formal and informal)?

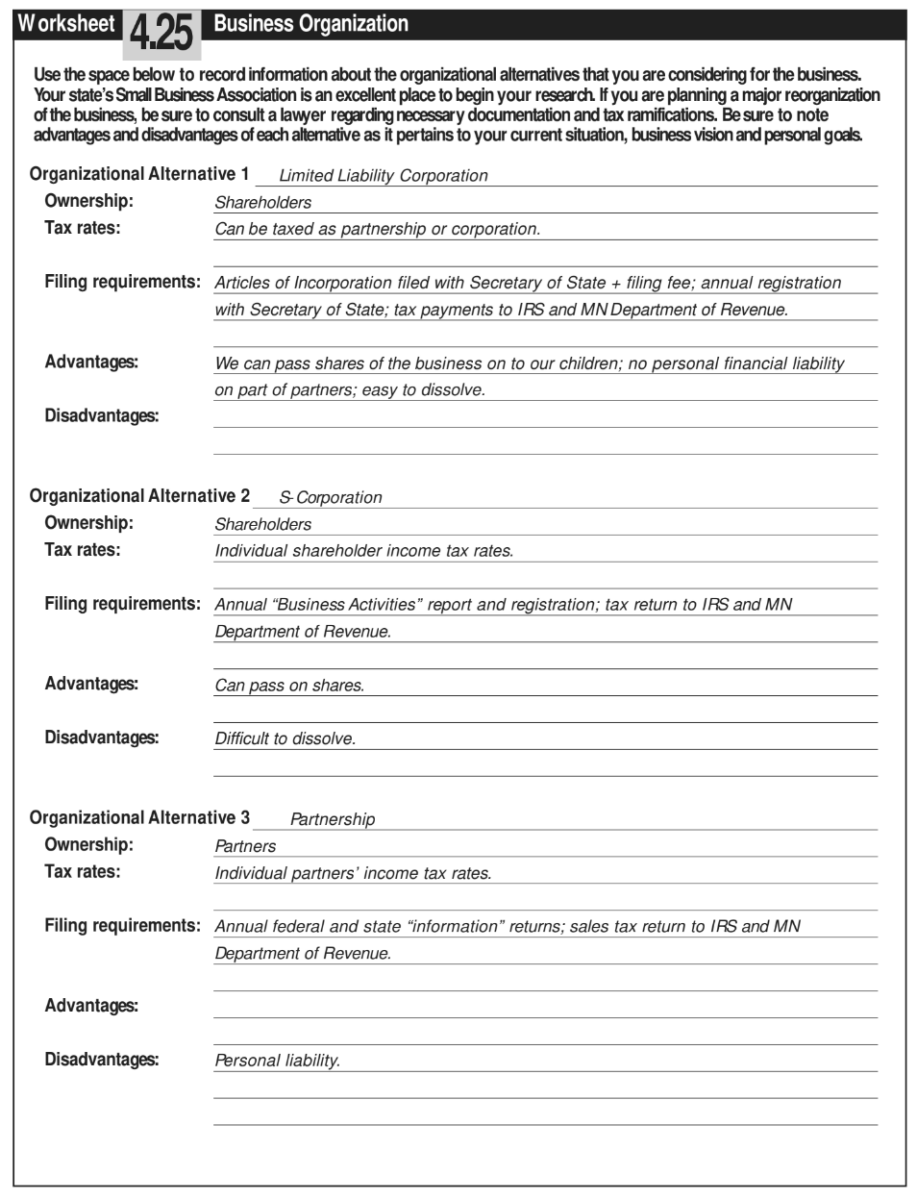

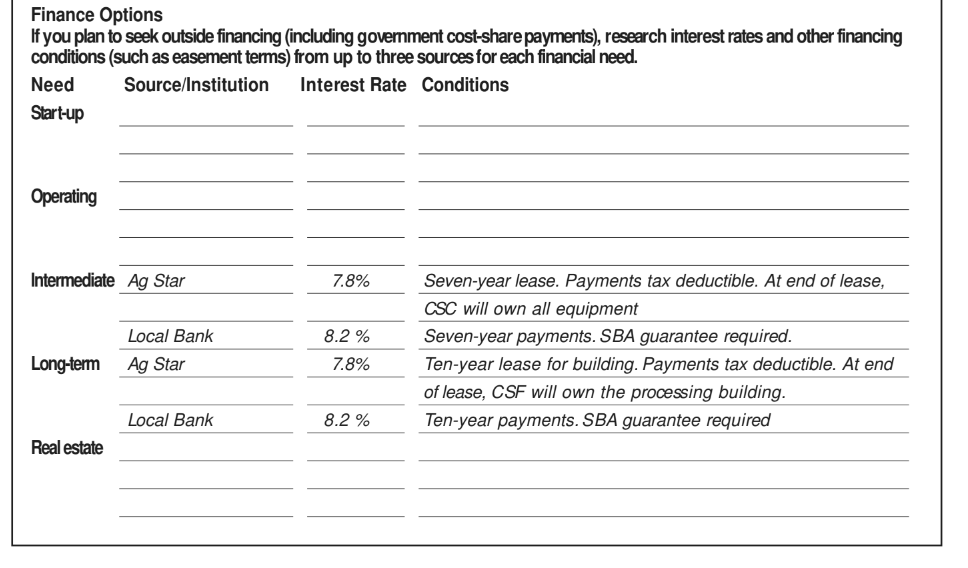

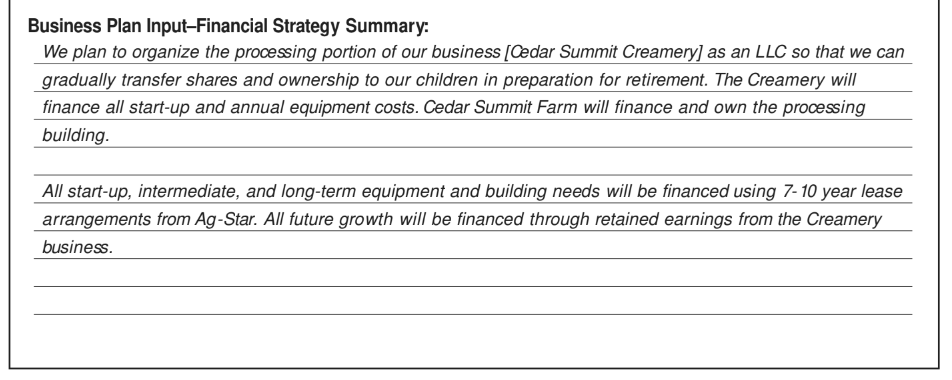

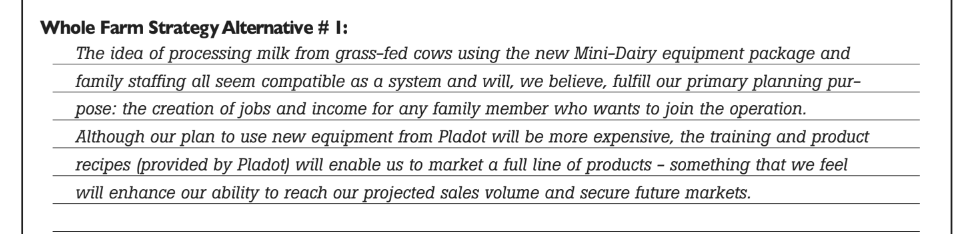

Making changes in your current resource use may mean making “better” use of underutilized resources. Based on your evaluation of current resource availability and future needs, are there any resources that are underutilized or that will become underutilized as you move toward your future vision? If so, one of your resource management strategies might be to “make better use of underutilized resources.” How you define “better” will depend on your values and goals. For example, it may mean sharing or renting out equipment with another family member or neighbor.