Planning Task Three

- Dream a vision for the future

- Develop a mission statement

- Set and prioritize goals

- Prepare the Vision, Mission, and Goals Section of your Business Plan

All of us do it—we dream. Whether from the seat of a tractor, while walking our pastures, or talking with family over coffee, we envision the future. This dreaming or visioning is critical to the business planning process. Visioning will help you identify the mission of your business—why it exists—and goals that will eventually form the basis of your business’ strategic plan. These three components—vision, mission and goals—make up Planning Task Three.

This Planning Task should be rewarding. It is a chance to imagine your future and set goals based on any short and long-term planning ideas that you have for your business. In the next chapter (Planning Task Four), you will research and evaluate your ideas to form a set of realistic business strategies. But for now, recall your values and dream a little as you work through developing a vision, mission statement and goals for your business. If you have participated in Whole Farm Planning, Holistic Management, or other workshops, you may have already gone through the visioning and goal setting process. Utilize any of this work and build on it in the questions and Worksheets that follow.

Dream a Future Vision

You’ve chronicled a history and described your current business situation. Now it’s time to sketch a future vision for your family and business. Your vision should paint a clear picture of how your business will function in the future, and incorporate personal values for family, community, the environment and income.

In the Introduction Worksheet: Why are You Developing a Business Plan? you identified a critical issue that motivated you to begin the business planning process. If you have ideas about how to address this issue, you should include it in your vision. For example, Dave and Florence Minar conceived of on-farm processing (prior to conducting any brainstorming or strategic planning) as a way to add value and jobs to their existing dairy business. This was their initial vision. It was the first idea that they researched and evaluated in Planning Task Four (Strategic Planning and Evaluation).

If you have identified a critical planning need but do not have clear ideas about how to address it, begin with a more personal vision for your business. Describe what role you would like to play in the business, what you will be doing. You’ll have an opportunity to brainstorm specific marketing, operations, human resources and finance strategies in Planning Task Four.

Begin the visioning process with some brainstorming. Ask what your farm or business will look like in five, ten, or twenty-five years. For example, what product(s) and services will you produce? Will you be working with animals or crops? What will the landscape and community look like? What role will you play in the business? Will you be working alongside family? Will you earn all of your income from the farm? Will there be time for regular vacations?

Include your planning team and even nonteam members in the visioning process. Although Dave and Florence Minar were already considering the idea of on-farm processing, they invited 15 family members and friends from the non-farm community to their home for a visioning session.Family and friends were divided into four groups. Each group was asked to develop “farm business ideas that will create jobs for the next generation of family members.” After an evening of brainstorming, each group came up with several new ideas ranging from the creation of a bed and breakfast/game farm to the purchase of a local creamery for ice cream production. Ultimately, the Minars rejected ideas that did not fit with their personal and environmental values, but they did incorporate the concept of ice cream production into their initial plan for on-farm dairy product processing.

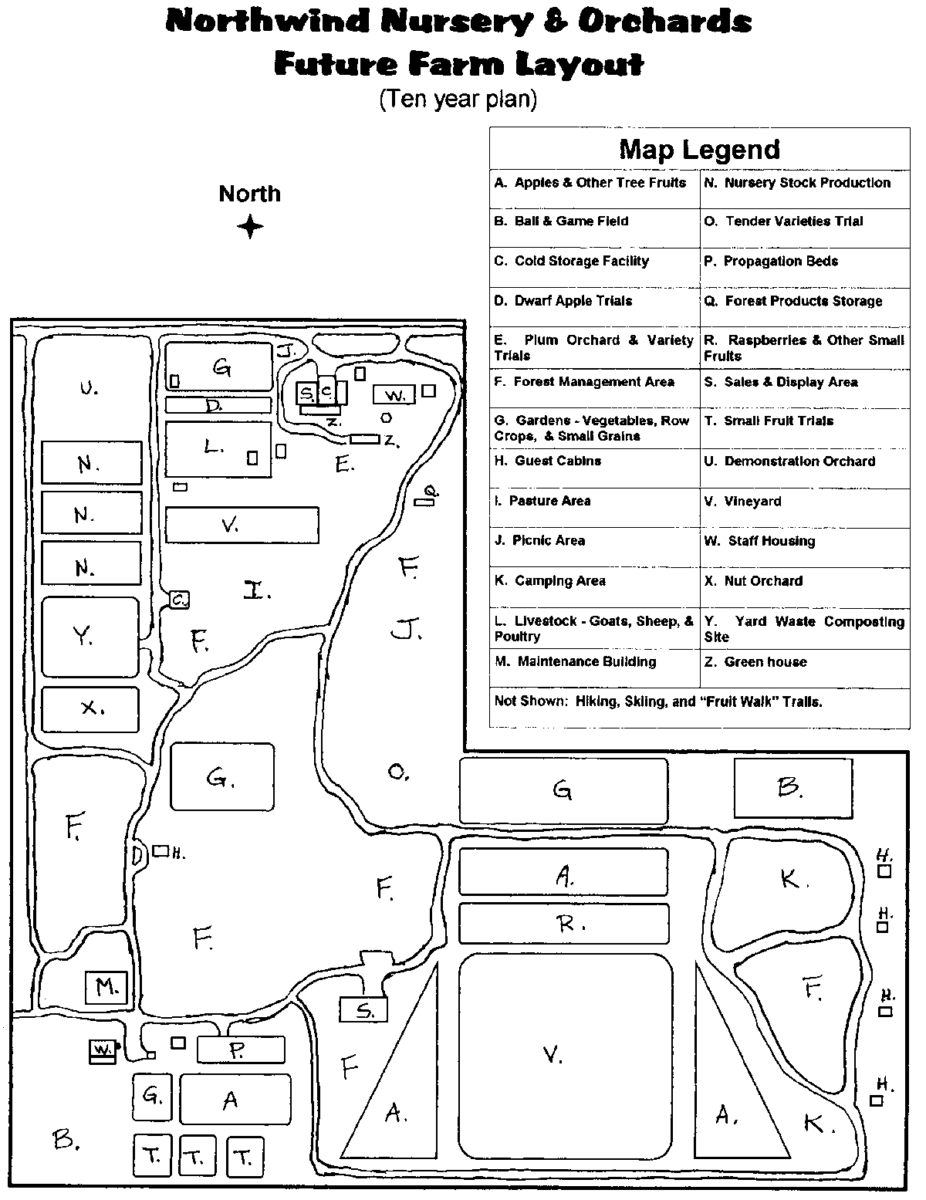

There are many ways to communicate your future vision: as a story, a short paragraph, a picture or even a map like that created by Northwind Nursery and Orchard owner Frank Foltz. Frank Foltz and his family agreed as part of their vision to continue selling nursery stock and farm-grown fruit in the future, but noted in his plan that “the most exciting concept we envision implementing is the experience of the farm itself.” The Foltz family drew two maps—one to reflect their current situation and one, like that shown in Figure 31, to reflect the service and tourism components of their envisioned nursery and orchard ten years from now, complete with guest cabins, a picnic area, a ball and game field, a demonstration orchard, and fruit trial areas as well as hiking, skiing and “fruit walk” trails.

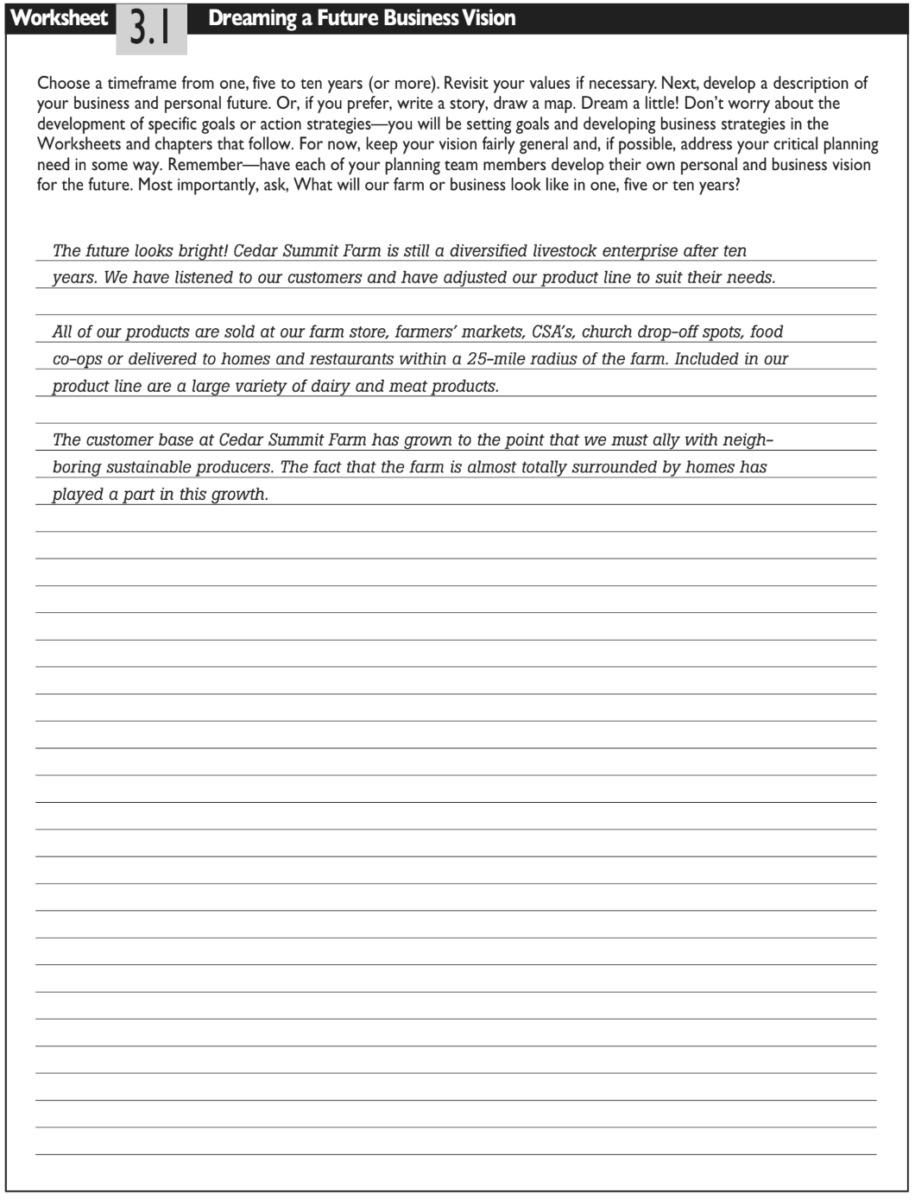

Use the questions in Worksheet 3.1: Dreaming a Future Business Vision (download worksheets for task 3) to begin developing a comprehensive future vision for your business. Be sure to involve your planning team members and remain open to new ideas. You may be surprised by what comes out of this process! Next, think about how you would like to share your vision with other family members, customers and potential investors and lenders—through a map, summary statement, story or list. Dave Minar’s Worksheet for Cedar Summit Farm is reproduced as Figure 32.

Develop a Mission Statement

A mission statement rolls your values, current situation and vision into a set of guiding principles that describe your business. It serves as a benchmark for you and your partners while communicating how and why your business exists to customers and other community members outside your business. It is, what Holistic Management author Allan Savory calls a “statement of purpose.”

Your mission statement may include values and beliefs as well as a product, market, management and income description. Moreover, it should draw from your future vision by including an overview of the direction in which your business is headed. It should be general and short, like the mission statement prepared for Riverbend Farm by owner Greg Reynolds:

“The mission of this farming enterprise is to produce organic food that: is sold to local customers at a fair price; will provide us with enough income; will improve the soil, air and water quality on our farm; and is a vehicle to raise community awareness of sustainability and environmental issues.”

Consider who will see your mission statement and bear this in mind as you write. For example, will you post your mission statement somewhere visible for customers to read like a label or brochure? What would you like your business to be known for—a particular quality such as “old-fashioned” taste, environmental stewardship, competitive prices? If the mission will remain within the business, think about how it can be used to inspire and motivate future members of the business.

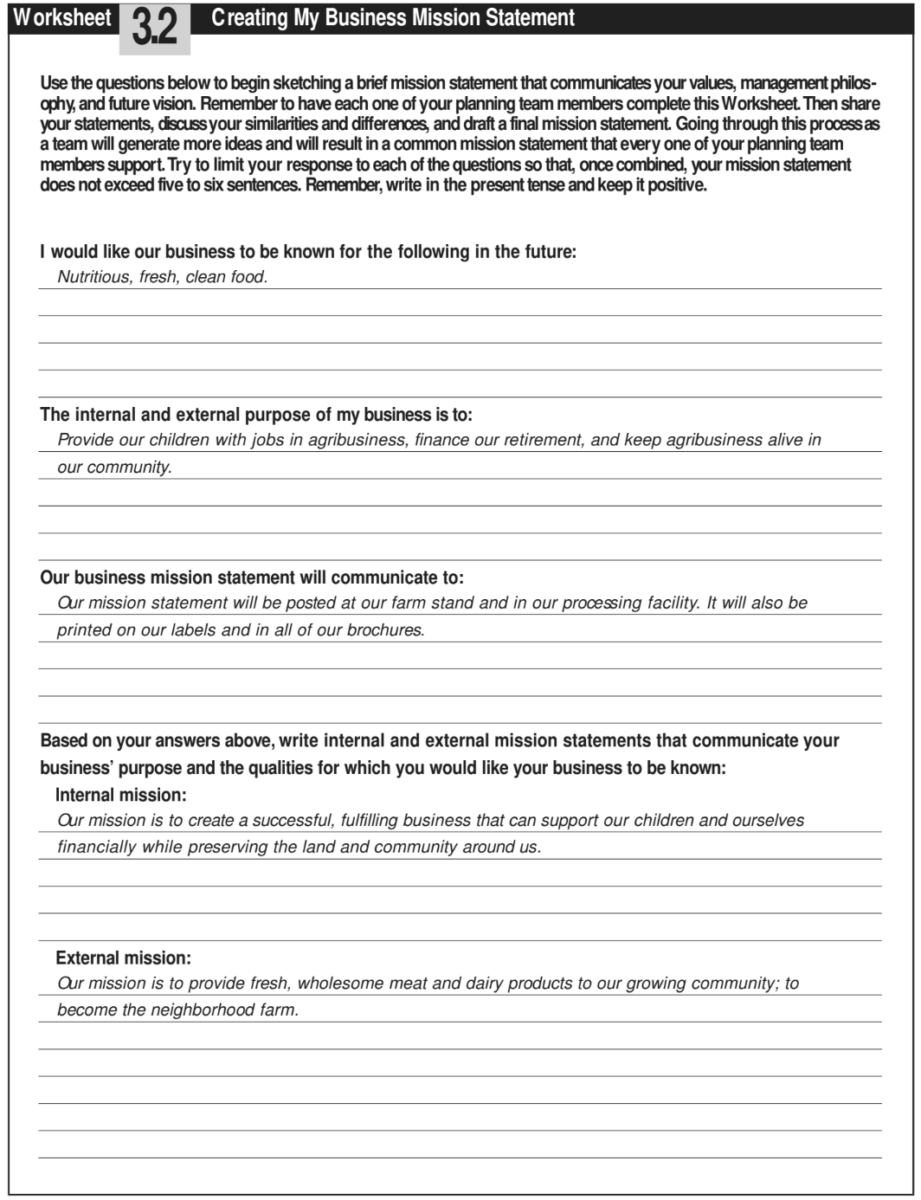

Draft a preliminary mission statement for your business. You will revisit this mission statement as you research, develop and evaluate business strategies for Planning Task Four. You can then make any necessary changes based on your research and strategic planning decisions. Limit your mission statement to five or six sentences and maintain a positive, active voice when writing. Think about these guidelines as you complete the statements in Worksheet 3.2: Creating My Business Mission Statement (download worksheets for task 3).

Set and Prioritize Goals

With a vision and mission in mind, you and your planning team are ready to begin the process of goal setting—that critical first step towards the development of a working strategic plan with measurable objectives.

Goal setting is important for all businesses—but it is especially important for family farms because they involve family. Clearly defined goals not only motivate and inspire, but they can also help mitigate conflict for families and help direct limited resources toward value-driven priorities.

Many lenders and other private institutions expect to see clearly identified goals as a part of a business plan. Lisa Gulbranson, author of Organic Certification of Crop Production in Minnesota, notes that “some [organic] certification agencies require that producers map out long-term goals and strategies” 7 as a part of their certification application. In this case, goal identification is not only a good idea, but is necessary.

What Are Goals?

Goals describe what you and your family would like to achieve—statements that point in the direction of your future vision for the business. They reflect the “what” and “who” pieces of your vision—what it is you would like to market, what the farm landscape will look like, who will be involved in operations, and what you intend to earn from the business. Goals do not describe the “how” components of your busines —how you plan to market and price a product, purchase equipment, staff the operation, etc. You will draft and test these “how to” strategy ideas in Planning Task Four.

Author Ron Macher notes that goals come in all shapes and sizes. “There are personal goals, family goals, business goals, community goals and environmental goals. A family goal,” he explains, “might be to develop a system of farming that allows you to spend more time with your children. A personal goal might be to have enough farm income to quit your town job and farm full-time. A business goal might be to achieve a 20 percent return on your total investment.”

Business goals can be broken down further into marketing, operations, human resources and finance objectives. As an existing business owner, for instance, you may have very specific goals for each functional area of the business—specific sales targets, workload limits, or profit objectives.

While these business goals will be unique to your business and personal values, one goal that is common to most business owners is some level of financial success. Although financial success may not be the most important goal of your farm business, it is usually in the mix. It is often very difficult to reach other personal, environmental, economic and community goals unless you reach a certain level of financial success.

Financial success can have many meanings. For one operator, it might mean making moderate financial progress or just breaking even while meeting other personal, business, and community goals. For someone else, it may not even be necessary to break even if there is another source of income to subsidize the farm. For another, the financial goal may be to make enough money to retire at age 60. There is no right or wrong—your goals should just reflect your personal values and be consistent with your own future vision.

As you sketch goals, think about your family’s desired standard of living. Estimate your future family living expenses using your current expenses (Worksheet 2.11: Family Living Expenses) as a starting point. Then factor in any quality of life changes that you foresee in the next two to ten years, such as the need to pay for college tuition, home improvements, retirement or travel as expressed by Dancing Winds Farm Owner Mary Doerr. Alternatively, if you are happy with your current standard of living, one of your goals might be to maintain current spending levels during the start-up phase of a new business enterprise. Be specific about how much income you will withdraw from the business annually to meet family or household living expenses. Will it supply all of your family living needs or only a portion? Worksheet 3.3: Estimating Our Family’s Goal for Profit (download worksheets for task 3) will help you estimate your family’s future family living expenses and goals for financial success.

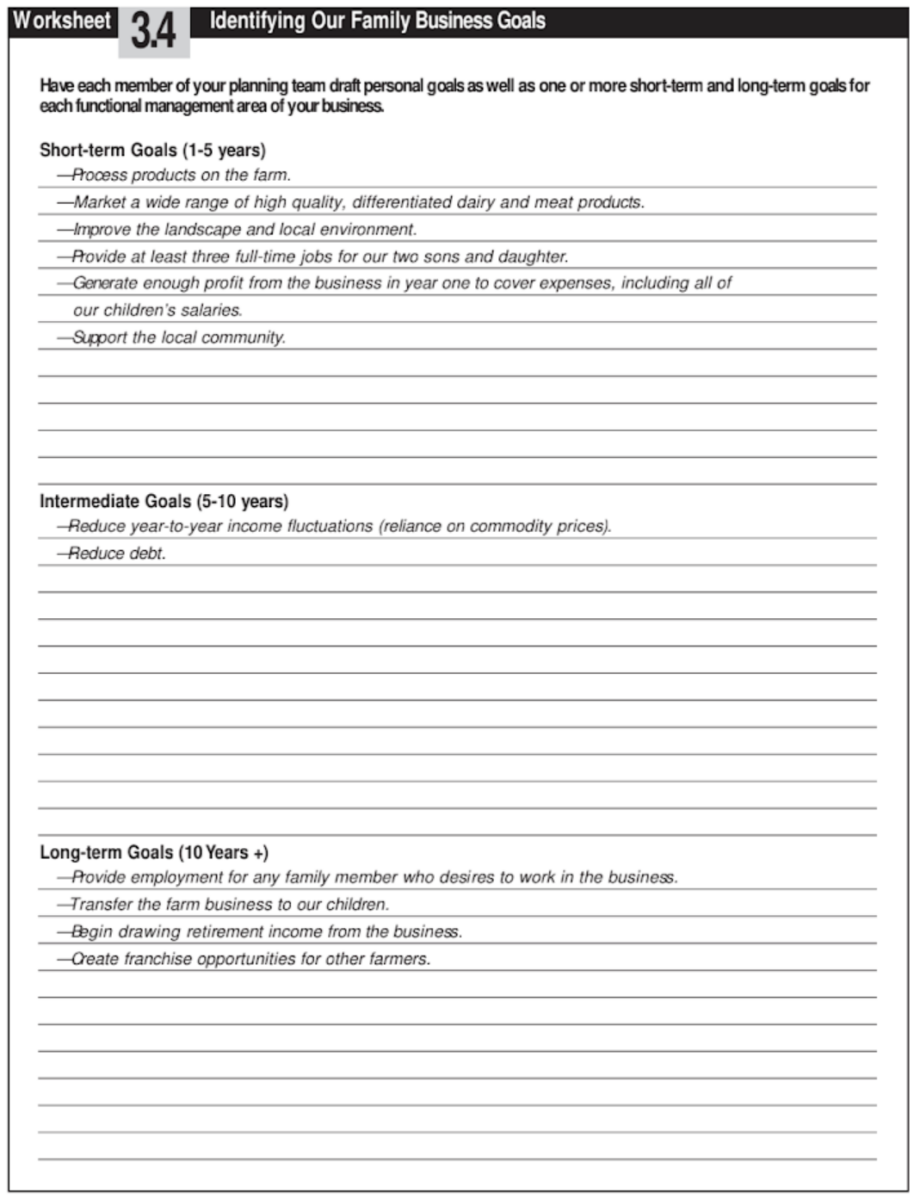

Regardless of what your goals are and how you choose to organize them, planning and goal setting can be made easier by defining a timeframe for each goal. The most common timeframes used for goals are a short-term horizon of one to five years, an intermediate horizon of five to ten years, and a long-term horizon of ten years or more. Look at the Minars’ goals (Worksheet 3.4, Figure 34) to get a feel for how these timeframes might be used. They combined personal goals for the community and environment with marketing, human resources and finance goals for the business. All of these goals, however, were broken out into short, intermediate and long-term timeframes.

Long-time business owner, Frank Foltz of Northwind Nursery and Orchards, outlined the following short and long-term goals for his business:

“Our immediate, short- term goal is to make a smooth transition from our current two- pronged (mail order and local) marketing approach to marketing entirely in our local community. While the mail order business has been profitable and offers much more opportunity for expansion, we feel the “local only” sales approach fits more with the values and mission of our business. . . . Therefore, we would like to sell the mail order portion of our business to a like-minded individual or family and begin a process of transition. This will eliminate a portion of our income and a portion of our workload.

. . . The lighter workload will enable us to initiate our next goal of a community-oriented nursery fruit farm and sustainable agriculture research facility where customers (community members) come to purchase products, learn how to grow their own fruit, and ‘experience’ a working farm. A long-term goal is to help other interested families establish their own small-scale, sustainable, agricultural enterprises, thus encouraging the restoration of the family farm and the revitalization of our rural communities.”

Frank’s task of creating specific goals was made easier by the fact that he has owned and operated his business for seventeen years. However, if you are just starting out or considering an entirely new business venture, your goals may be a little more general and personal in nature like those drafted by organic wheat producer Mabel Brelje:

“Prior to 1998, my short-term goal was to convert my farm to organic standard, which has been accomplished. Currently, my short-term goals include sharecropping to overcome ongoing labor and equipment deficiencies while working toward my longer term goal—to sell the farm to a family or organization who will continue to manage it organically and maintain it as a showplace . . . Once the farm sale is complete, I intend to remain active as a consultant and to pursue another lifelong goal: writing.”

You may use Worksheet 3.4: Identifying Our Family Business Goals (download worksheets for task 3) to spell out your family’s goals. With these goal-setting ideas in mind, you are ready to:

- Write out individual goals

- Identify common goals

- Prioritize goals

Figure 35. Groups Goal Setting - Reconciling Different Goals

“A question that arises is how business owners can reconcile their different goals. The individuals that ask this question have already set their own goals and shared them with their family and co-owners. It is at this point in the process that they realize there are differences that need to be resolved. One observation in answering this question is that the goals of family members and co owners do not need to, and never will, be identical. It is not reasonable to strive to establish one set of goals that fits everyone.

Yet goals cannot be so divergent that there is nothing in common. Instead, group members should strive to find commonalities among their goals and opportunities to work together to accomplish tasks that fulfill goals of several individuals. For example, there may be an activity that fulfills goals for several people even though they are different goals. The key to working out differences among goals appears to be communication and willingness to cooperate.”

Write Out Goals.

As an experienced business owner or as a far-sighted entrepreneur, you may have very clear goals and objectives for each component of your business. Or, instead you may choose to develop personal, economic, community and environmental goals. It’s up to you. The main idea is to get your goals, whatever they may be, down on paper. Written goals will give you “checkpoints” to follow— something to revisit as you evaluate strategic alternatives (Planning Task Four) and monitor your plan following implementation (Planning Task Five).

Identify Common Goals.

Once you and your planning team members have identified goals individually, you should take time to discuss and share them with your planning team. This will enable you to identify common goals, recognize differences, and establish a set of collective priorities for the family and business. “Do not ignore potential conflicts or restrictions that might prevent reaching goals. Identifying possible problems in the planning stage will allow time to resolve conflicts,” explains Extension educator Damona Doye.

Figure 35 describes a few guidelines for group goal setting. If you are having trouble reconciling different goals, mediation services are available to facilitate family discussions. Contact the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Farm Service Agency or your local extension service for more information about certified mediators.

Prioritize Goals.

Once you are comfortable with the collective business goals identified by you and your planning team, you are ready to begin prioritizing. Few businesses or families have enough resources to reach all of their goals at one time. Prioritized goals “provide clear guidelines for management decisions.”

For example, Riverbend Farm owner Greg Reynolds’ goal, “to take a couple of weeks off in the summer,” may seem modest, but it is one that he and his family identified as a priority. Summer is typically the busiest time of year for Riverbend Farm since it specializes in vegetable production and Greg rarely has time away from the business during this season. Therefore, Greg’s business strategy—to hire additional labor—was built around his critical planning need (labor shortages) and one of his top goals (to have time off during the summer).

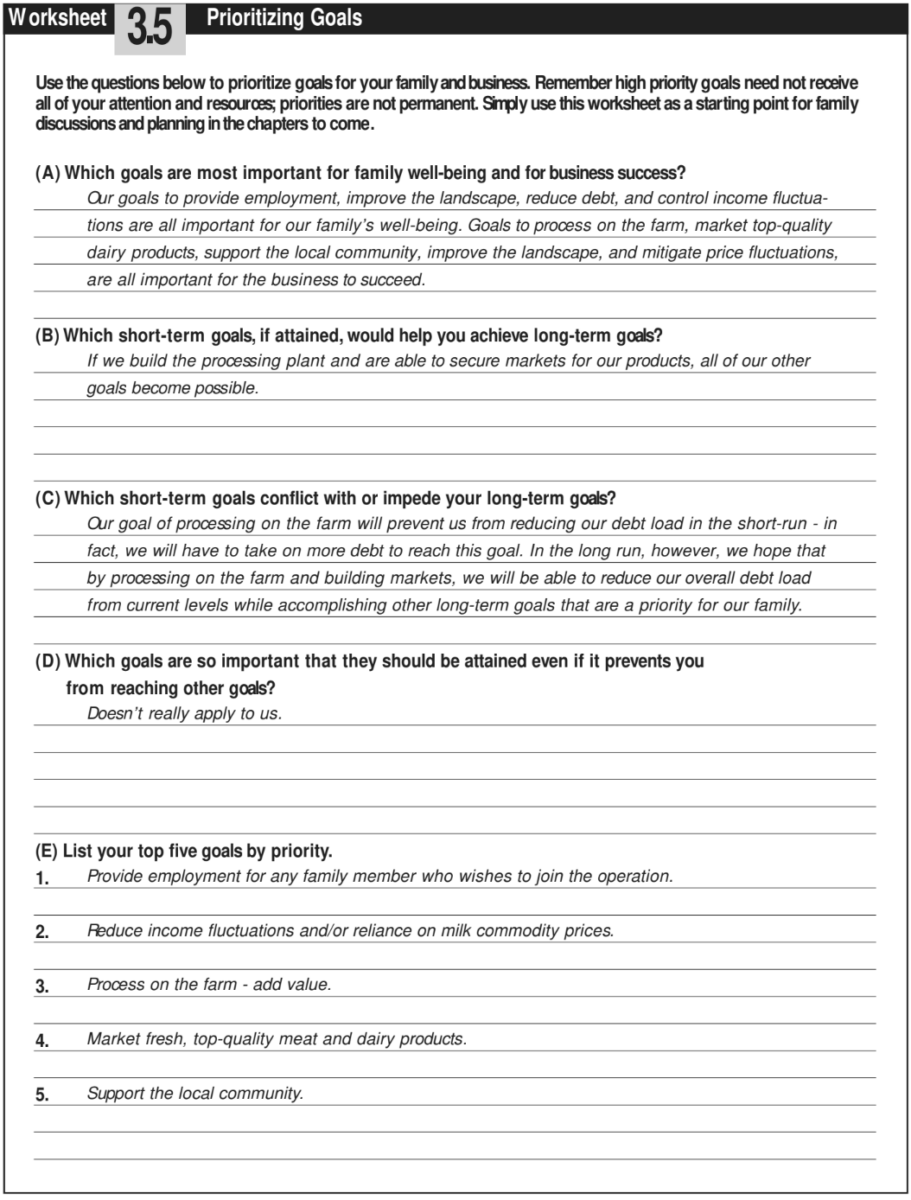

This task of prioritizing your goals won’t necessarily be easy since many goals may overlap or conflict. The Minars, for example (Figure 36), envisioned building a processing plant in order to reach their family goals. This idea, however, conflicted with a financial goal to reduce their debt load.

The idea here is to identify which goals are most important to your family and for your business—to determine which goals are worth pursuing even if they prevent you from reaching other goals. Worksheet 3.5: Prioritizing Goals (download worksheets for task 3) includes questions to help you with this task.

Prepare the Vision, Mission and Goals Section of Your Business Plan

Your vision, mission and goals statements are likely to change as you conduct research and develop an overall business strategy in Planning Task Four (Strategic Planning and Evaluation). The Minars, for example, spent weeks on their initial visioning process. However, after analyzing the feasibility of on-farm processing and deciding to implement this strategy, they ultimately chose to include only a short statement about the business component of their vision: “Our vision is to process and direct market all of our milk and meat products. We would like to help other farmers direct market their own products, possibly by creating a franchise for milk processing plants.”

Your draft business plan might include the elements shown here.