Longest-running experiment in the Mid-Western U.S. demonstrates the economic and soil-health benefits of cover crops as cattle forage.

Whether you graze cover crops with livestock or you hay it, you get an economic benefit even if it impacts your next crop yield.”

—Dr. Augustine Obour, Research and Education Grantee

Crop-Livestock Integrated Systems are Economically Viable

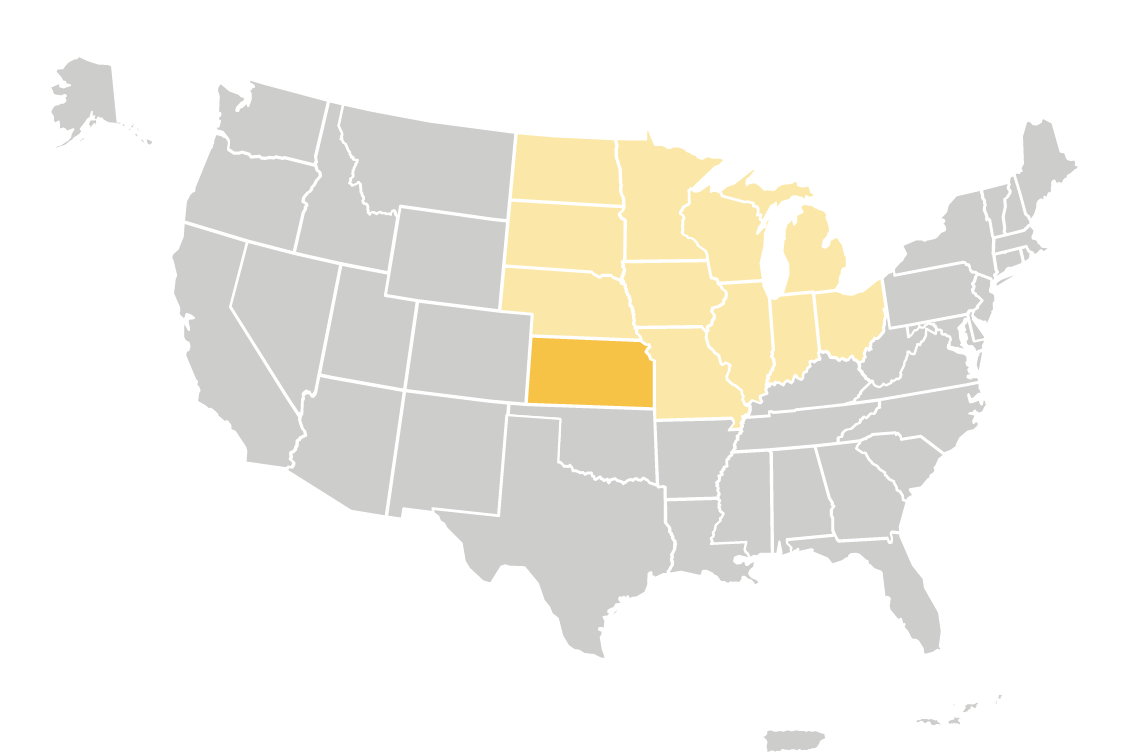

Region: North Central

State: Kansas

Grant Type: Research and Education

Grant: LNC18-411

SARE POST-PROJECT EVALUATION IMPACT MODEL

This evaluation impact model is specific to this SARE-funded project.

Sustainability Impacts

The project grantees and stakeholders contributed to the following sustainability impacts:

- Environmental sustainability impacts

- Economic sustainability impacts

- Production efficiency impacts

Grantee Indicators

(University Researcher)

Project grantees (defined above) achieved sustainability impacts by engaging with the following indicators through involvement with project activities:

- Increased knowledge/skills

- Increased capacity/motivation

- Increased engagement

- Practice change

- Career growth

Stakeholder Indicators

(Graduate Students, Producers, Agricultural Service Providers, Consultants)

Project stakeholders (defined above) achieved sustainability impacts by engaging with the following indicators through involvement with project activities:

- Increased knowledge/skills

- Increased capacity/motivation

- Increased engagement

- Practice change

- Career growth

The Success Story

In the semiarid central Great Plains, drought conditions increasingly contribute to crop failure and soil erosion. Cover crop integration is a promising ameliorative strategy that generates harvestable forage for the region’s livestock and offsets cash crop revenue loss. As part of the only long-term (8 years in 2024) grazing cover crop experiment in the Western U.S., Dr. Obour and his research team demonstrated that replacing a fallow treatment (with herbicide application) with a crop-livestock integrated system achieves a net economic benefit while improving soil health. With data to support the benefits of this climate-smart practice, policymakers now encourage cover crop grazing and farmers are reaping the benefits.

Good for Profits and Good for the Soil

—Dr. Augustine Obour, Research and Education Grantee

You can graze these cover crops and when you take the cattle out, there is regrowth. We found that the amount of biomass with grazing and without it is not statistically significant. You can sustainably graze and still have enough biomass to cover the soil. We also found there is no significant difference in soil compaction, soil nutrient concentrations, or soil organic carbon content.”

Grantee (Researcher) Highlights

As a university-based professor, Dr. Obour is reliant on grant funding to propel his research. He has successfully sustained cover crop research at the Kansas State University Agricultural Research Center-Hays since 2015, prolifically publishing and presenting on the findings. From these activities, Dr. Obour has built a reputation as a soil management and agronomic production expert in the North Central region and in Ghana, where he first began studying crop science at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science & Technology.

Other Stakeholder (Graduate Students, Producers, Agricultueral Service Providers, Consultants) Highlights

Dr. Obour relied heavily on a master’s degree student, Mr. Logan Simon, who collected most of the soil measurements for the project. Simon was subsequently admitted as a PhD student in Agronomy, with Dr. Obour serving as his advisor. A SARE graduate student grant is funding his research to determine the optimum amount of cover crop biomass removal to balance grazing and soil-health goals. Simon, who graduates in 2024, has already been hired as an Assistant Professor at Kansas State University. The farmers who opened their land for Dr. Obour’s on-farm research project continue to employ forage cover cropping. Trusted sources of guidance that farmers rely on, including agriculture consultants and NRCS staff, are now advocating for the practice. This has led to farmers throughout the region experimenting and adapting their plots from season to season, deepening knowledge about the timing and crop types that generate the greatest benefit in varied contexts.

Trusted Sources Spread the Word

I’ve seen a lot of seed dealers and private agronomists promoting cover crops as a forage resource. At a recent Northwest Kansas focus group meeting, one person specifically mentioned our experiment. NRCS is using the information as a training tool for their employees, and more and more people are signing up for NRCS programs on grazing cover crops. I’m excited NRCS has accepted the idea of grazing cover crops. The information is getting out there. With that, I think there will be more adoption.”

—Dr. Augustine Obour, Research and Education Grantee

Sustainability Impacts

Prior to this project, it was believed that using cover crops for forage would reduce biomass inputs to a degree that exposed the soil to erosion. By demonstrating that grazing does not cause this negative impact, more farmers are adopting the practice. Environmental sustainability impacts include reduced soil erosion, improved nutrient cycling, suppression of herbicide resistant weeds, and improved soil health. Producers employing the practice also benefit from enhanced crop profitability as they produce forage for the region’s livestock. While the project began as a cover crop experiment, it is evolving to examine crop-livestock integrated systems as a climate-smart tactic in the face of unpredictable weather. Even if the primary grain crop grown on the land fails, the cover crop can be grazed or harvested, contributing income to the enterprise while concurrently improving soil quality.

The challenge in getting people to adopt this practice is not research, but crop insurance. ... I hear from producers that if you plant a cover crop, it is perceived as though you are doing a continuous crop. ... The insurance adjustors take that into consideration, expecting increased risk of crop failure. Something needs to be worked out so those who adopt cover crops have the same premium incentives or benefits as those who practice summer fallow.”

—Dr. Augustine Obour, Research and Education Grantee

The Insurance Industry Lags Behind

Barriers

Complex economic issues pose ongoing challenges to adoption of cover crops for cattle forage in the region. While the study demonstrated net economic gains during the grant period, the cost of cover crop seed has since increased, driven by federal subsidies. In cases where a cover crop is planted but not used for forage or hay production, the net revenue is now less than would be generated by leaving the plot fallow and applying chemical herbicides. Crop insurance is also problematic, as adjustors assume cover cropping increases the likelihood of crop failure. This is because, prior to Dr. Obour’s research, it was believed that cover crops’ water use would reduce subsequent cash crop yield and increase instances of crop failure.

Contributors

On-farm research is vital to demonstrate that research findings generated at university experimentation sites are transferrable to large-scale production settings. SARE’s unique emphasis on farmer partnerships made possible Dr. Obour’s validation of preliminary findings that have justified recommending the practice more broadly to farmers.

On-Farm Research Elevates Farmers' Perspectives

Most grants don’t have a farmer requirement, but SARE does. It is very helpful because farmers have different perspectives on what works and what doesn’t. As a researcher, you may have some ideas, but you have to work with a farmer to determine what will work in their environment. ... We had a farmer who planted sudangrass, radishes, and rapeseed; some of them grew to be five feet tall. I thought that was a great thing having a lot of biomass out there, but he wants to see the cattle, so next time he won’t plant anything that grows that tall.”

—Dr. Augustine Obour, Research and Education Grantee