Producer association builds robust regional network through SARE grants that support farmers to evolve with changing markets.

We couldn’t have done it without SARE. [The association] would have been a total washout. Our philosophy as an association is to put money into the farmer’s pocket, not take it out. Our dues are very low and there’s no fee for membership. We have close to 400 members, and maybe 20 of those pay dues. Without income from SARE, none of this would have been possible.”

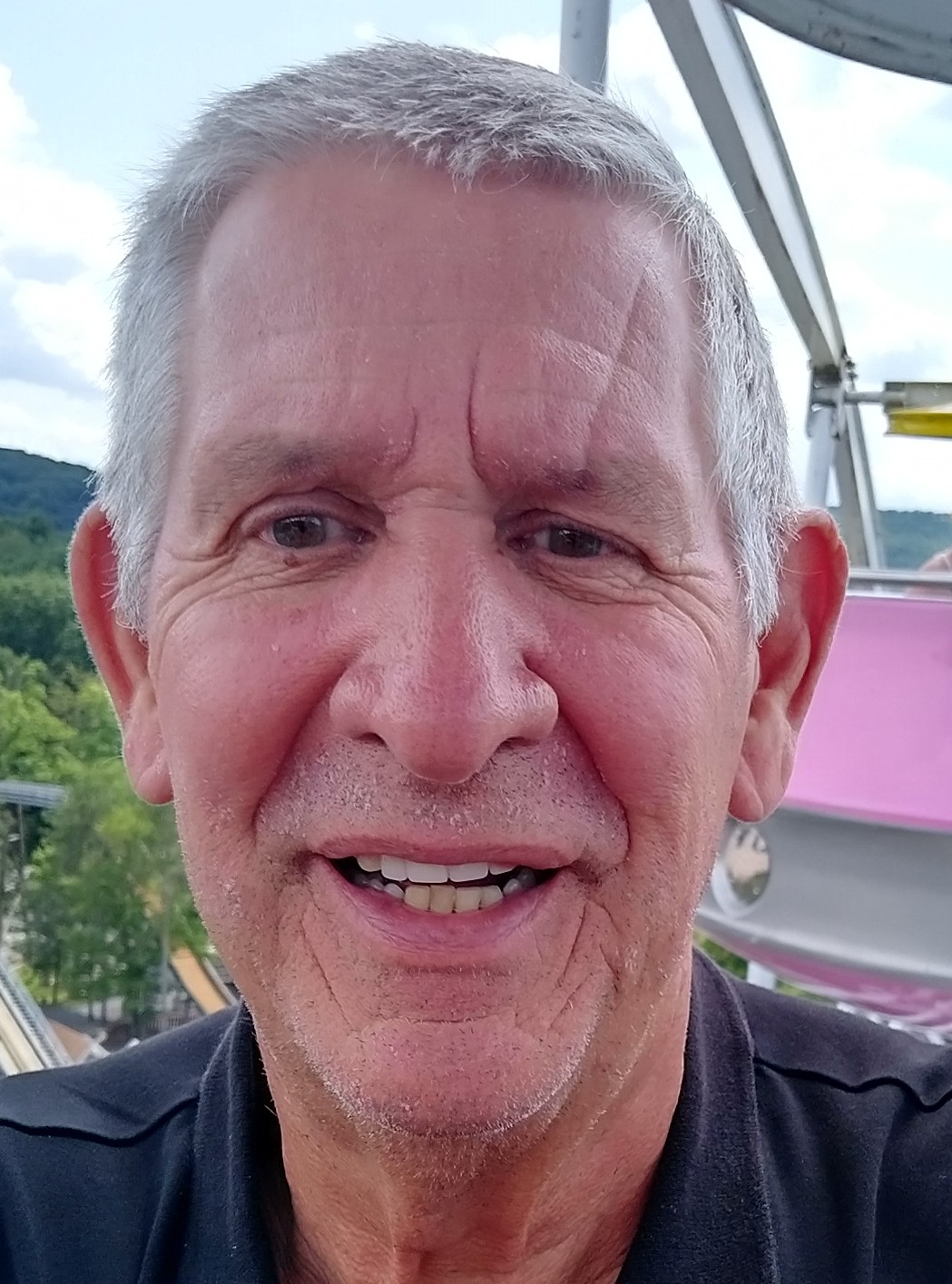

—Will Brandau, Farmer Grantee

Bolstering a Productive Grower Community

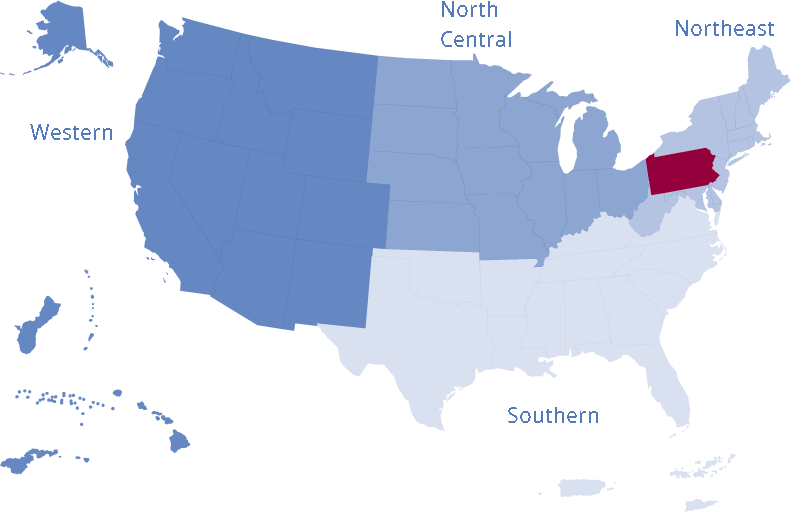

Region: Northeast

State: Pennsylvania

Grant Type: Farmer

Grant: FNE17-865

SARE POST-PROJECT EVALUATION IMPACT MODEL

This evaluation impact model is specific to this SARE-funded project.

Sustainability Impacts

The project grantees and stakeholders contributed to the following sustainability impacts:

- Environmental sustainability impacts

- Economic sustainability impacts

- Production efficiency impacts

- Social sustainability impacts

Grantee Indicators

(Farmers)

Project grantees (defined above) achieved sustainability impacts by engaging with the following indicators through involvement with project activities:

- Increased knowledge/skills

- Increased capacity/motivation

- Increased engagement

- Practice change

Stakeholder Indicators

(Farmers)

Project stakeholders (defined above) achieved sustainability impacts by engaging with the following indicators through involvement with project activities:

- Increased knowledge/skills

- Increased capacity/motivation

- Increased engagement

- Practice change

- Career growth

The Success Story

In Pennsylvania, the Association of Warm Season Grass Producers markets the many economic and environmental benefits of using warm season grasses, including switchgrass. Since 2016, in partnership with university extension specialists, association members have executed a series of grants (GNE16-127, FNE17-865, ONE18- 320, ONE19-346) that have furthered knowledge of processing and distribution methods for various markets. SARE’s ongoing support, in combination with committed volunteers, has been instrumental in developing the association’s robust membership.

We all had these guys experimenting with different processes on how to produce poultry bedding that was less than an inch and a half in length and dust free. ... We took all the things that worked and put them together on one device that was portable so it could go from farm to farm. We wrote another SARE grant and were given money to build that machine.”

—Will Brandau, Farmer Grantee

Grantee (Farmer) Highlights

Will Brandau, the farmer grantee, has built a strong social network through his involvement with the association. Members nominated him to serve as chairman at its inception, a role he continues to enjoy. Based on his learning about switchgrass, Brandau opted to grow it on his farm. He found this perennial grows well as a crop, even on rocky land with minimal tending, requiring just two weeks of labor to harvest every year.

Other Stakeholder (Farmers) Highlights

Today, two farmers are producing switchgrass bedding with methods developed through SARE grants. For example, Trumbower Farms produces 100 acres of switchgrass that is sold at eight locations. The farm is also selling the leftover dust from processing switchgrass to a mushroom producer who uses it as a growing medium. Many other producers connected to the association are growing switchgrass for various purposes. In 2019, the association developed a warm season grass producer directory that now spans Arkansas, Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania.

A Low-Effort Crop With Many Benefits

The root system goes way down into the ground—there’s no erosion. The soil improved drastically. The water running off the fields improved drastically. It was a filtration system. I’ve met a lot of other farmers because of the association and their involvement with switchgrass. People call me on the phone to this day. I love talking about switchgrass.”

—Will Brandau, Farmer Grantee

Sustainability Impacts

The many environmental sustainability benefits of switchgrass include improving: 1) air quality by removing carbon from the atmosphere; 2) water quality by reducing soil erosion through root system sequestration of nitrogen and phosphorus; 3) soil quality through reduced erosion, and 4) wildlife habitat for a range of species from pollinating insects to white-tailed deer. Under good market conditions, switchgrass is also a profitable, low-labor commodity that farmers can grow in rocky, untillable soil.

The market has pretty much dried up for big time sales. At one point, silt sock producers were chasing all over looking for switchgrass. Farmers were selling it for $150 a ton and they had so much less work to do. When that market dried up, many of them switched back to corn and soybeans. Why wouldn’t they? They’re getting a government subsidy for every bushel they produce and there’s no supplement for switchgrass.”

—Will Brandau, Farmer Grantee

Variable Markets are an Ongoing Challenge

Barriers

Identifying economically viable, stable markets for switchgrass has been an ongoing challenge. The project team primarily marketed their product to county fairs and farm shows that used it in their poultry displays, enlightening producers to the product’s benefits. After an avian flu outbreak interrupted that effort, sales spiked when switchgrass was identified as a superior stuffing for “silt socks” (tubes of biodegradable material laid down for erosion control). Propelled by gas industry use, the price increased from $65 to $150 per ton in 2018. As public support for pipeline construction waned, however, so did the need for switchgrass. The association has strong collaborations with Penn State and Cornell extension specialists who continue to promote switchgrass as a lower-cost bedding material. Brandau hopes US producers, informed by these educators, will adopt switchgrass for cattle bedding, a practice with significant uptake in Canada.

Contributors

A combination of relevant experience and free time enabled Brandau to contribute substantially to the association’s development. His prior professional experience included running computer systems for jet engine aero parts manufacturing and owning an amusement park. In these settings, he developed technical and entrepreneurial skills that served him well in writing grant proposals and conducting research with large switchgrass processing machines. Brandau got involved in the Pennsylvania warm season grass producer community in semi- retirement when he began seeking a viable crop for the family farm he had inherited. He has generously dedicated his free time to building up the association through grant writing, maintaining the website, facilitating gatherings, and engaging with members to address their needs.

Grants Take Time and Expertise

It’s a lot of work. Not only do you need to do the work listed in the grant, you need to write reports about the grant progress. The facilities where we’re planting the trial lots are close enough to me that I can visit them regularly to see the progress and take photographs and videos to put into the yearly report. The average farmer is not going to take the time to do all the work that’s required.”

—Will Brandau, Farmer Grantee