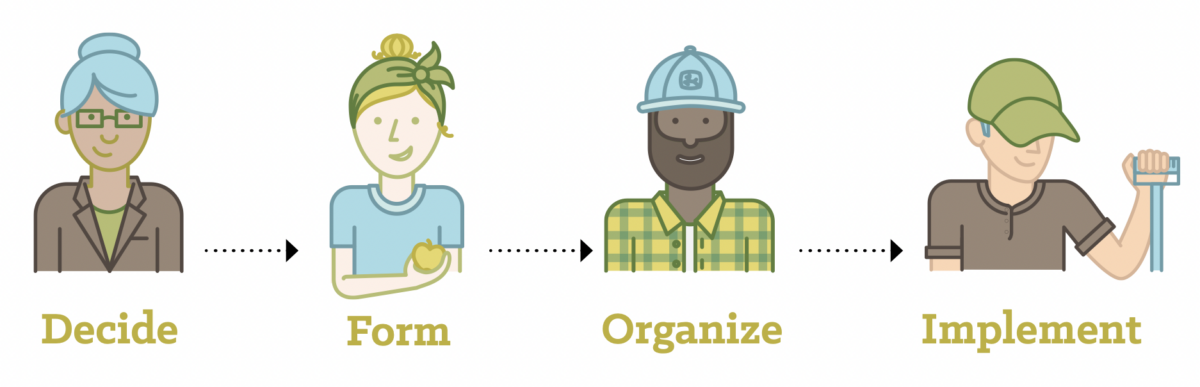

Decide

This can seem daunting at first; there are just too many entities to choose from. However, considering just a few factors will automatically narrow down your options. The following entity comparison chart reviews basic legal issues and implications associated with the various business entities. Turn to Chapter 2 for a user-friendly flowchart. Just answer a few questions and you will identify the best place to start. If you are lucky, the entity will choose you!

Don’t stop at the flowchart. The detailed chapters on each of the entities that follow provide incredibly important, detailed information on the structure and nature of the entity. Read the chapter corresponding to the entity that chooses you in the flowchart exercise. These chapters also contain supplemental materials including checklists and sample organizing documents to help walk you through the steps in forming that particular entity.

Before taking any action, be sure to read chapter 10 on anti-corporate farming laws. Certain Midwestern states have laws that affect a business’s ability to own or control farmland and farm businesses. You’ll need to confirm that your plan doesn’t violate an anti-corporate farming statute if you live in one of these Midwestern states.

We also strongly recommend working with an accountant or tax professional before taking any action. Businesses overall come with very specific tax and accounting issues with varying complexities. These financial issues should not be handled in isolation. While this Guide provides some information about tax issues to get a person started, this Guide does not serve in any way as tax advice. Tax matters are very specific to individual factors, including the farm’s specific operations, the owners’ financial situation and the entity chosen. This Guide does not address state tax issues at all. Obviously, state tax matters are still a vital consideration.

An accountant’s input early on is an investment in later efficiency. An accountant or tax professional can really help with the process of setting up the business, such as creating spreadsheets and financial tracking mechanisms. Good accounting practices and systems can provide insight into the business, help eliminate bad debt, manage cash flow issues, create favorable tax strategies and ease the processes of payroll and maintaining profit and loss statements, to name a few.

Once you’ve confirmed your business entity selection is right for your farm operation and is not counter to any anti-corporate farming statute, you’ll next need to pull the rest of your team together to generate consensus. The team members may include your spouse, business partners and any potential investors.

An attorney can be another key team member. The attorney’s role will be to confirm that your selection of business entity is most suitable for your farm operation based on your state’s business entities laws. Again, each state has a specific statute for each type of entity. These statutes vary from state to state. Each one may have fewer or more restrictions on types of ownership and decisionmaking power and fewer or more requirements on upholding certain formalities, among other factors. Working with an attorney who is familiar with your state’s business entities statutes provides assurance that your choice is wise and your business organization documents will be upheld.

Form

Deciding on a business entity is just the first step. The next step is actually forming the entity in your state. (Or, if you’ve chosen a default entity, the next step is to do nothing!) This step involves preparing a formation document. The formation document is either called the “articles of incorporation” (C corporation, B corporation, cooperative or nonprofit corporation) or the “articles of organization” (LLC). This document is filed with the state agency responsible for business registration, which is usually the state’s secretary of state office. It typically requires a fee that varies based on both the state and the specific entity. The fee can range anywhere from $40 to $1,000. The filing fee, as well as any required annual maintenance fees, can be a huge factor in which entity to choose. Be sure to look into this thoroughly before filing. Once the articles are filed and approved, the business entity is recognized as official. The chapters on each of the business entities provide detailed explanations about the formation process.

Federal recognition of distinct business entities for tax purposes

Business entities are traditionally the responsibility of the states. The entity is created at the state level, and the state’s statutes govern baseline operating rules. But, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) still needs to tax the enterprise. The IRS’ tax classifications may be slightly different than the state’s entity classifications.

For example, an LLC or corporate entity may want to be classified as an

S corporation with the IRS. Or, a nonprofit may want classification as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. In addition, certain farmer cooperatives or consumer cooperatives selling agricultural products are eligible to receive special tax benefits if they meet specific IRS requirements outlined in the federal tax code. We provide enough information to help farmers get a sense of the IRS’ expectations for each business entity. But again, farmers will need to work with an accountant or tax preparer for advice on tax matters.

Organize

Creating the organizing document

An organizing document defines how the business entity will operate. While the formation document is always required, the organizing document may be optional depending on your entity. In addition, while the formation document must be filed with the state, the organizing document does not. It is a private document that principally serves as a contract between and among the owners.

What’s in an organizing document

The organizing document prescribes the decision-making procedures, roles, responsibilities and other administrative matters for running high-level operations of the business. This includes: How is voting determined? Who has a say on big issues such as selling a significant amount of the business’s assets or closing the business entirely? When are major meetings held? Can new owners be brought on and, if so, what is the process? What happens if a business owner wants to leave or dies suddenly? What happens if the business voluntarily or by force has to close? How is the business valued? Day-to-day matters such as budgeting procedures, production standards and quality parameters are not usually included in an organizing document. Most businesses choose to write these issues into separate policy documents, which they write at the same time as the organizing document itself. Policy documents are kept separate, so they are a bit easier to modify as the business evolves. The organizing document is written to be modified rarely, if at all.

Organizing Document By Entity

| Entity | Organizing Document | Required? |

|---|---|---|

| Sole Proprietorship | None | Not required |

| General Partnership | Partnership Agreement | Not required |

| Non-Associated Nonprofit | Bylaws | Not required |

| LLC | Operating Agreement | Not required in most states* |

| C Corporation | Bylaws | Required |

| B Corporation | Bylaws | Required |

| Cooperative | Bylaws | Required |

| Nonprofit Corporation | Bylaws | Required |

| *LLC operating agreements are not required except in California, New York, Missouri, Maine and Delaware. New York is the only state that requires operating agreements to be in writing. | ||

What are the benefits of an organizing document?

Most new business owners are optimistic and eager to build their farm business. Even thinking about worst-case scenarios like the death of a partner seems like a waste of valuable time. However, thinking through the worst cases is much better at preventing horror stories from developing than sticking one’s head in the sand.

Going through the process of creating an organizing document helps business owners kindly and judiciously address important matters that can, and indeed have, quickly ruined a farm business. The process of deeply thinking through such matters can really help build trust and understanding between the owners and enhance a relationship built on respect and shared objectives. And, if a dispute were to arise, the organizing agreement can assure a quick resolution if it outlines responsibilities and resolutions. Mediation, arbitration and dispute resolution committees can all help businesses get back on track after a problem develops. But, these mechanisms are much easier to put in place before a problem ever occurs.

Putting decisions in writing protects the memories and shared understanding of the founding owners and educates new owners about expectations. Writing it all down also helps to spot inconsistencies and conflicts.

How do you get an organizing document?

The ultimate goal is to get a thorough, affordable and understandable document that addresses your farm’s situation specifically. How is this possible? One option is to pay an attorney to do all of it for you. Getting a standard organizing agreement drafted will likely cost around $1,000. Of course, the fees could be a lot higher depending on the complexity of the operation and the going legal rates in your region, especially if you are near an urban center. The base amount is for a pretty standard, boilerplate agreement. It may be great and serve many of the beneficial purposes outlined above. On the other hand, you may not really understand what it all means, and at a cost of $1,000, it still may not be affordable for many small farm operations.

Another option would be to get a form from the library, through a quick internet search, or from a friend. This may seem appealing; all you have to do is swap out the names. While this may be the most affordable option, it will certainly not be catered for your specific farm operation. Also, there’s no guarantee of the quality or thoroughness. Most likely, it will simply serve as a bare-bones skeleton and will not provide many of the benefits that a well-thought-out, written agreement can provide as listed above.

A third option, and the one for which this Guide advocates, is to educate yourself on the key aspects of an organizing document. This Guide can help you with that. Checklists and samples of organizing documents are included as tools. The checklists will walk you through a series of questions. Once you have your answers, one option is to start doing some of the legwork yourself by pulling together a draft organizing document. For this step, you can turn to the sample organizing documents included in the Guide, which contain provisions that you can draw from to develop an operating agreement that is best suited for your farm operation. The annotations include alternative provisions for a variety of scenarios. Keep in mind that these sample agreements are not boilerplates, as they were written with a particular farm operation in mind. Yours should be different. Farm Commons strongly urges you to find an attorney who can help you draft, finalize or review the organizing document. Interview the attorney and let them know you have done your homework. Ask them about their pricing and try to get a sense of their willingness to work with you to keep your costs down. Many attorneys out there are very sensitive to such requests.

Either way, it is very important to have an attorney review and finalize your work. This is primarily because organizing documents must comply with the baseline requirements set forth in the state statutes. The requirements vary from state to state. If your organizing document is in conflict with state law, it may be deemed void and unenforceable if an issue or dispute were to arise. In that case, all your effort would be futile.

Despite many farmers’ inherent skills in problem-solving, it can be challenging to create a consistent organizing document where none of the provisions conflict with each other. If two provisions conflict, it only creates confusion. Which provision applies? All that effort and intention to set clear expectations among the owners goes out the window. An attorney can help assure you that your organizing document has no internal conflicts.

While doing some or all of the legwork yourself takes more time, it will be less expensive than paying an attorney to do it all. In addition, you’ll reap the added benefit of gaining a lot of knowledge throughout the process. You’ll know exactly how your business operates.

Implement good business practices

All formal business entities have to uphold certain formalities and best practices to maintain the entity’s integrity. Otherwise, all the benefits of having an entity, such as special tax treatment and protection of the owners’ personal assets from the business’s liabilities, could be taken away. Primarily, this includes keeping the business’s financial affairs separate from the owners’ financial affairs, including maintaining separate bank accounts, credit cards and accounting systems. In addition, the business entity must not recklessly spend money and incur a lot of debt, otherwise courts could determine that the entity is undercapitalized and use the members’ personal assets to cover the business’s liabilities. Implementing good business practices also includes filing annual fees, obtaining required licenses and registrations, keeping up to date on tax filings and so on. The default entities–the sole proprietorship, general partnership and the unincorporated nonprofit association–must also uphold such good business practices. Each chapter on a specific entity has an Implementing Good Business Practices section that explains each of these requirements and practices in more detail.