Other common names:

- Ivyleaf morningglory: common morningglory, ivy-leafed morningglory, entireleaf morningglory

- Pitted morningglory: small white-flowered morningglory, white morningglory

- Tall morningglory: common morningglory, purple morningglory

Ivyleaf morningglory, Ipomoea hederacea Jacq.

Pitted morningglory, Ipomoea lacunosa L.

Tall morningglory, Ipomoea purpurea (L.) Roth

Identification of Morningglories

Family: Morningglory family, Convolvulaceae

Habit: Twining summer annual herbs

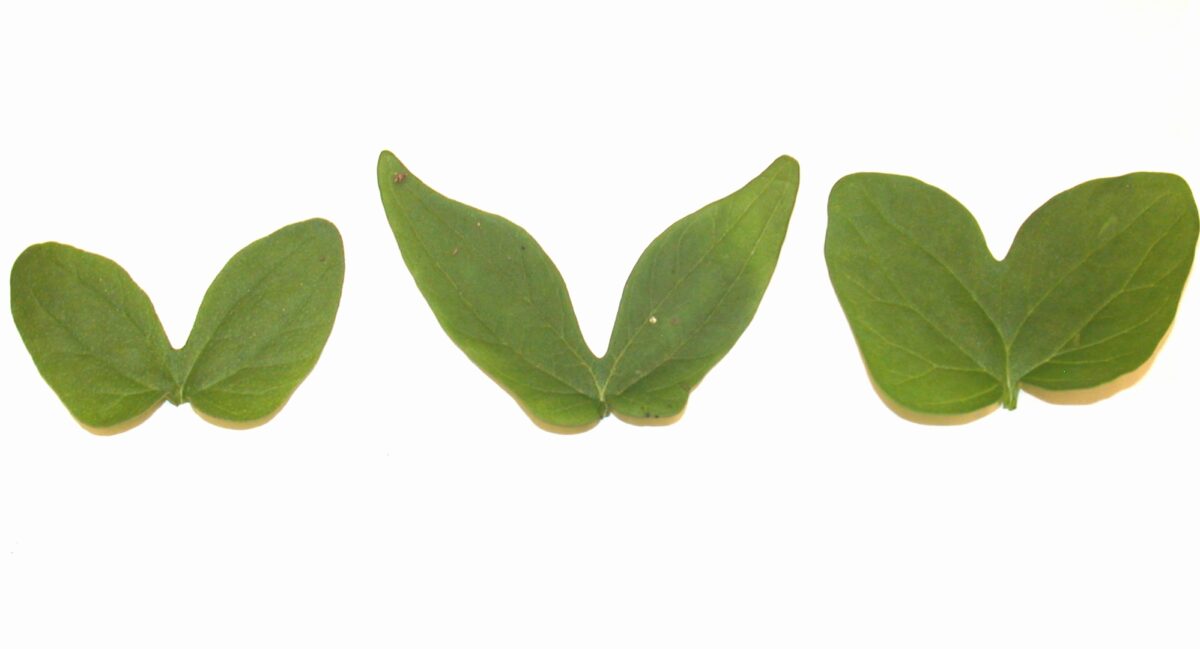

Description: Seedling stems are green to maroon and ridged. Cotyledons are two lobed, hairless, symmetrical and green.

- Ivyleaf morningglory: Cotyledons are deeply notched at the tip and slightly notched at the base, forming a butterfly shape. Each 0.6–1.75 inch-long by 0.6–1.5 inch-wide cotyledon fits within a square to rectangular or trapezoidal outline. The first true leaf is unlobed, heart shaped and hairless. All other true leaves are three lobed, with upright hairs on both blade surfaces, stems and leaf stalks.

- Pitted morningglory: Cotyledons are split more than 75% of their length into a V and have narrower and pointier lobes than tall and ivyleaf morningglories. Fully expanded cotyledons are 1.9 inch long by 2.6 inches wide at the broadest point. All young leaves are heart shaped and tapered to the tip. Leaves are nearly or completely hairless.

- Tall: Cotyledons are green, 0.6–1 inch long by 0.6–1 inch wide, butterfly shaped and fit into a square outline. All young leaves are heart shaped and covered in small hairs that lie parallel to the leaf surface.

Mature plants trail and climb by twining, branching stems that can reach 12 feet, although 6.5 feet is more common. Leaves are alternate. Roots are coarsely branched.

- Ivyleaf morningglory: Stems are hairy. Leaves are 2–5 inches long by 2–5 inches wide, tri-lobed and covered in upright hairs; leaves generally have a heart-shaped base and tapered lobes.

- Pitted morningglory: Stems are smooth. Leaves are nearly hairless, up to 3.7 inches long by 3.1 inches wide, heart shaped and tapered to a narrow, pointy tip. A small taproot is present.

Tall morningglory: Stems are hairy. Leaves are heart shaped with a blunt tip and basal lobes that may overlap slightly. Leaves are 2–5 inches long and nearly that wide and are covered with appressed hairs.

Flower petals are fused into a funnel shaped flower with many stamens and three pistils. Clusters of flowers form in leaf axils.

- Ivyleaf morningglory: Petals are 1.1–2 inches long, initially off-white to light blue but turning pink-purple after opening. Clusters of one to three form in each leaf axil. Thin, hairy or bristly, green, 0.5–1 inch-long sepals curve backwards at the tip.

- Pitted morningglory: Petals are 0.6–0.8 inch long and characteristically white to pinkish. Otherwise, the flowers resemble those of ivyleaf morningglory.

- Tall morningglory: Petals are 1.75–2.75 inches long and light colored when young, turning purple-pink or blue as they open and mature. Clusters of three or more form in each leaf axil. Narrow, lanceolate sepals are 0.5 inch long and clasp the base of the fused petals. Otherwise, the flowers resemble those of ivyleaf morningglory.

Fruit and seeds: Flowers produce egg-shaped capsules that remain partially concealed by the remaining sepals. Capsules contain two to four (usually three) compartments. Seeds are dark brown to black and wedge shaped. Seeds have two flat and one round side.

- Ivyleaf morningglory: Each capsule produces four to six seeds. Seeds are large, almost 0.25 inch wide and covered in minute hairs.

- Pitted morningglory: Each capsule produces four, 0.2 inch-wide, smooth seeds.

- Tall morningglory: Each capsule produces four to six 0.2 inch-diameter seeds, similar to those of ivyleaf morningglory.

Similar species: Several other morningglory species exist, with smallflower morningglory [Jacquemontia tamnifolia (L.) Griseb.] being of great importance in the southern United States. It can be distinguished from the morningglories described above by the dense appressed hairs on the foliage and by its tight clusters of small, bright blue flowers. Bindweeds, such as field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis L.), are often confused for true morningglories. Bindweeds are perennials, whereas the weedy morningglories discussed here all arise from seeds. Wild buckwheat (Polygonum convolvulus L.) is a twining annual that has leaves resembling pitted morningglory, but wild buckwheat has small green flowers and sheaths extending up the stem from the base of leaves.

Management of Morningglories

Morningglories are difficult weeds to control, and their vining habit makes them aggressive competitors. Early planting dates for corn, soybeans and cotton allow the crop to become competitive before most of the morningglories emerge. If morningglories emerge and vine before the crop canopy closes, substantial crop yield losses can result. Tine weed aggressively to break or bury newly emerged seedlings. You may need to do this more frequently than for smaller seeded, and therefore slower growing, weeds. Because many emerge from deep layers of the soil, relatively few can be uprooted, and rotary hoeing is likely to be less effective than tine weeding. To avoid crop damage, cultivate frequently enough to kill morningglories before inter-row plants have attached to crops. If possible, use a belly mounted cultivator or accurate guidance system with shallow pitched half sweeps to get close to the rows. Shorter season crop varieties may allow harvest before the vines interfere severely with harvesting equipment. Consider setting the combine to capture morningglory seeds with the grain, and then clean them out later or use equipment to capture or destroy seeds in the chaff. Flame weed in well-established cotton while morningglory seedlings are still small.

Winter wheat suppresses morningglory establishment by keeping the soil cool and undisturbed during the peak germination period. Seedlings that do emerge are suppressed by shade. A dense, vigorous stand of spring grain has a similar effect, provided the grain is planted early. Morningglories are favored by short annual crop rotations like alternating peanuts and cotton, so diversifying rotations to include an established sod during the warm periods of the year will suppress morningglory populations.

Although some seeds will likely survive solarization, even a few days at 140–158°F in moist soil eliminates a large proportion of pitted morningglory seeds. Both plastic and straw mulch are ineffective for controlling morningglories. The vines find their way through the planting holes in plastic—they are essentially led to the crop by light. Large seed reserves allow the seedlings to emerge through 6 inches or more of straw.

Ecology of Morningglories

Origin and distribution: Ivyleaf morningglory probably originated in tropical America. Authorities disagree about whether tall and pitted are native to the Southeast and southern Midwest or were introduced from the American tropics. Ivyleaf morningglory is now widely established east of the Rocky Mountains and in the Southwest. Pitted morningglory occurs from Massachusetts to Iowa and south to Florida and Texas, and also in California. Tall morningglory is native to tropical America but is now established in most of the United States. All three species are most problematic in warm, humid regions, and their occurrence tends to be scattered in the northern and western states.

Seed weight: Ivyleaf morningglory, 27–35 mg; pitted morningglory, 19–25 mg; tall morningglory, 19–25 mg.

Dormancy and germination: Usually, a high percentage of morningglory seeds have a hard seed coat that prevents them from absorbing water and thereby maintains dormancy. A substantial proportion of recently matured seeds of all three species will germinate, but germination declines after the seed coat hardens. Seeds require exposure to moist conditions or high relative humidity (as occurs in spring) to become sensitized, followed by high temperatures (as occurs in early summer) to break dormancy. However, dry conditions (as occurs in late summer) will desensitize seeds so dormancy is not broken by high temperatures. Seeds germinate best at warm temperatures (59–95°F). Moistened seeds of pitted morningglory germinated best at these warmer temperatures, but seeds with broken seed coats germinated equally well at day/night temperatures from 59/43°F to 95/68°F. Pitted morningglory germination was more tolerant of drought than several other weed species including ivyleaf morningglory. Pitted morningglory germinated best at pH 6–8, whereas tall morningglory germinated well at a pH range of 5–7. Light generally has little effect on germination of morningglory species, but it did promote germination of tall morningglory seeds that had been buried in the soil. Seeds of tall morningglory germinate poorly in soil with low oxygen. This is not directly due to excess carbon dioxide or a lack of oxygen but occurs because seeds in a low oxygen environment produce volatile organic compounds that enforce dormancy. Venting of volatiles during tillage would promote germination. Flooding also greatly reduced germination of tall morningglory.

Seed longevity: Morningglory seeds can have a relatively long life in soil because of their hard seed coats. Ivyleaf mornigglory seeds can persist after burial for up to 17 years. However, more typically, 36% and 70% of ivyleaf seeds disappeared between late autumn and the following August, and mortality was little affected by depth of burial. Pitted morningglory seeds buried at 22 inches had 31% survival after 39 years. In contrast, in another experiment, only 13% of pitted morningglory seeds remained viable after burial for 5.5 years. When a sowing of pitted morningglory was tilled annually to 6 inches and no seed return was allowed, the number of seedlings emerging declined by 58% per year.

Season of emergence: All three species have some emergence throughout the warm months of the year, but peak emergence tends to occur in early summer. Studies in Illinois showed flushes of ivyleaf emergence primarily in June and July following rainfall. Out of 23 summer annual weeds tested, ivyleaf morningglory was the latest emerging species in spring but had the longest emergence duration once it began emerging.

Emergence depth: Generally, all three species emerge best from the top 1–2 inches of soil, but substantial numbers can emerge from 4 inches. A few individuals can even emerge from 6 inches. Tall morningglory seeds at 0.5 inch emerged faster and plants became more competitive with crops than seeds emerging from 2 inches.

Photosynthetic pathway: C3

Sensitivity to frost: The first frost usually kills morningglory plants.

Drought tolerance: Ivyleaf morningglory does not compete effectively for soil moisture. Tall morningglory is more susceptible to drought than cotton. Tall morningglory responds to drought by allocating more resources to leaves while maintaining overall biomass compared to control plants, but reproduction is reduced.

Mycorrhiza: Tall morningglory is mycorrhizal. Data are lacking for the other two species.

Response to fertility: Ivyleaf is a poor competitor for N and grows poorly without N fertilization. Tall morningglory responds to low N by allocating more resources to roots than control plants, but overall growth and reproduction are severely reduced. Tall morningglory is more responsive to soil P and K than corn or soybeans but less responsive than forage grasses. It grows poorly on soils with a pH below about 5.3.

Soil physical requirements: Pitted morningglory tolerates poor soil drainage.

Response to shade: Large seeds and a viny growth habit often allow morningglories to escape competition for light by climbing up competing plants. Light interception by the crop leaf canopy must exceed 90% for suppression of ivyleaf morningglory. Cotton competitively suppressed newly emerging ivyleaf once the crop leaf canopy closed, but plants still produced a few seeds. Rapid canopy closure in narrow-row soybeans suppressed pitted morningglory growth. Tall morningglory has longer internodes, longer stems, thinner stems and larger leaves when growing in shade. These shade-responsive traits are enhanced when support is available, allowing the species to climb and access light within a crop canopy, even when it emerges after the crop. But tall morningglory is unable to flower in shade.

Sensitivity to disturbance: Ivyleaf morningglory has a high potential to recover from removal of the growing tip when vines are greater than 4 inches long.

Time from emergence to reproduction: Ivyleaf morningglory flowers four to seven weeks after emergence. Tall morningglory flowers six to eight weeks after emergence. Seeds of both species mature about four weeks after flowers open, and plants continue to flower and set seeds until they are killed by frost. Pitted morningglory tends to flower as days shorten to 13 hours in late August, regardless of whether they emerge in May or late June.

Pollination: Ivyleaf morningglory is primarily self pollinated, and flower structure indicates that pitted is likely self pollinated as well. Tall morningglory has a high rate of cross-pollination (70%), mostly by bumblebees and small butterflies. The prevalence of self-pollination in ivyleaf morningglory flowers is explained by the close proximity of anthers and stigma, whereas this distance is highly variable in the outcrossing tall morningglory. Also, the larger and more conspicuous flowers of tall morningglory attract more bumblebees and provide greater potential pollinator energy gain than do ivyleaf flowers. Self-pollination incurs no penalty; outcrossed and self-pollinated populations of tall morningglory perform similarly in response to drought or nitrogen stress.

Reproduction: Plants emerging mid-summer and growing without competition often produce about 5,000–7,000 seeds, but under good conditions plants can produce as many as 11,000 (ivyleaf), 16,000 (pitted) and 26,000 (tall) seeds. Crop competition, however, greatly decreases seed production. For example, pitted morningglory competing with soybeans produced only 5% and 0.4% as many seeds as plants growing without competition in two successive years. A study of ivyleaf morningglory showed that plants emerging in early July produced the most seeds, with earlier and later emerging individuals producing substantially fewer seeds.

Dispersal: Given the similarity of morningglory seeds to seeds of field bindweed and their hard, impermeable seed coat, the seeds probably pass through livestock and are spread with manure. Since deer frequently feed on morningglory, they may spread the seeds as well. These species probably also disperse when seeds in contaminated feed grain pass through livestock.

Common natural enemies: Ivyleaf morningglory can be heavily damaged by white rust (Albugo ipomoeae-panduratae) and orange rust (Coleosporium ipomoea) but produce thousands of seeds per plant anyway. Tall and pitted morningglory are less damaged by rusts. Tall morningglory (and probably other species) can be heavily attacked by tortoise beetles (Deloyala guttata and Metriona bicolor), the sweet potato flea beetle (Chaetocnema confine) and the corn earworm (Heliothis zea).

Palatability: Ivyleaf and tall morningglory have better digestibility and higher crude protein than warm season forage grasses, but they are deficient in P.

Summary Table of Morningglories Characteristics

| Morningglories | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth habit | Seed weight (mg) | Seed dormancy at shedding | Factors breaking dormancy | Optimum temperature for germination (F) | Seed mortality in untilled soil (%/year) | Seed mortality in tilled soil (%/year) | Typical emergence season | Optimum emergence depth (inches) |

| vining | 19–35 | Yes | scd, wst | 59–95 | 36–70 | 58 | summer | 1–2 |

| Photosynthesis type | Frost tolerance | Drought tolerance | Mycorrhiza | Response to nutrients | Emergence to flowering (weeks) | Flowering to viable seed (weeks) | Pollination | Typical & high seed production (seeds per plant) |

| C3 | low | low | yes | high | 4–8 | 4 | both | 300 & 15,000 |

Table Key

General: The designation “–” signifies that data is not available or the category is not applicable.

Growth habit: A two-word description; the first word indicates relative height (tall, medium, short, prostrate) and second word indicates degree of branching (erect, branching, vining).

Seed weight: Range of reported values in units of “mg per seed.”

Seed dormancy at shedding: “Yes” if most seeds are dormant when shed, “Variable” if dormancy is highly variable, “No” if most seeds are not dormant.

Factors breaking dormancy: The principle factors that are reported to break dormancy and facilitate germination. The order of listing does not imply order of importance. Abbreviations are:

scd = seed coat deterioration

cms = a period subjected to cold, moist soil conditions

wst = warm soil temperatures

li = light

at = alternating day-night temperatures

ni = nitrates

Optimum temperature range for germination: Temperature (Fahrenheit) range that provides for optimum germination of non-dormant seeds. Germination at lower percentages can occur outside of this range. The dash refers to temperature range, and the slash refers to alternating day/night temperature amplitudes.

Seed mortality in untilled soil: Range of mortality estimates (percentage of seed mortality in one year) for buried seeds in untilled soil. Values were chosen where possible for seeds placed at depths below the emergence depth for the species and left undisturbed until assessment. Mortality primarily represents seed deterioration in soil.

Seed mortality in tilled soil: Range of mortality estimates (percentage of seed mortality in one year) for seeds in tilled soil. Values were chosen for seeds placed within the tillage depth and subjected to at least annual tillage events. Seed losses are the result of dormancy-breaking cues induced by tillage, germination and deterioration of un-germinated seeds.

Typical emergence season: Time of year when most emergence occurs in the typical regions of occurrence for each weed. Some emergence may occur outside of this range.

Optimum emergence depth: Soil depths (in inches below the soil surface) from which most seedlings emerge. Lower rates of emergence usually will occur at depths just above or just below this range.

Photosynthesis type: Codes “C3” or “C4” refer to the metabolic pathway for fixing carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. Generally, C3 plants function better in cooler seasons or environments and C4 plants function better in warmer seasons or environments.

Frost tolerance: Relative tolerance of plants to freezing temperatures (high, moderate, low).

Drought tolerance: Relative tolerance of plants to drought (high, moderate, low).

Mycorrhiza: Presence of mycorrhizal fungi. “Yes” if present; “no” if documented not to be present, “unclear” if there are reports of both presence and absence; “variable” if the weed can function either with or without, depending on the soil environment.

Response to nutrients: Relative plant growth response to the nutrient content of soil, primarily N, P, K (high, moderate, low).

Emergence to flowering: Length of time (weeks) after emergence for plants to begin flowering given typical emergence in the region of occurrence. For species emerging in fall, “emergence to flowering” means time from resumption of growth in spring to first flowering.

Flowering to viable seed: Length of time (weeks) after flowering for seeds to become viable.

Pollination: “Self” refers to species that exclusively self-pollinate, “cross” refers to species that exclusively cross-pollinate, “self, can cross” refer to species that primarily self-pollinate, but also cross-pollinate at a low rate, and “both” refers to species that both self-pollinate and cross-pollinate at relatively similar rates.

Typical and high seed production potential: The first value is seed production (seeds per plant) under typical conditions with crop and weed competition. The second value, high seed production, refers to conditions of low density without crop competition. Numbers are rounded off to a magnitude that is representative of often highly variable reported values.

Further Reading

Elmore, C.D., H.R. Hurst and D.F. Austin. 1990. Biology and control of morningglories (Ipomoea spp.). Reviews of Weed Science 5: 83–114.

Gomes, L.F., J.M. Chandler and C.E. Vaughan. 1978. Aspects of germination, emergence, and seed production of three Ipomoea taxa. Weed Science 26: 245–248.

Leon, R.G., D.L. Wright and J.J. Marois. 2015. Weed seed banks are more dynamic in a sod-based, than in a conventional, peanut-cotton rotation. Weed Science 63: 877–887.

Oliveira, M.L. and J.K. Norsworthy. 2006. Pitted morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) germination and emergence as affected by environmental factors and seeding depth. Weed Science 54: 910–916.