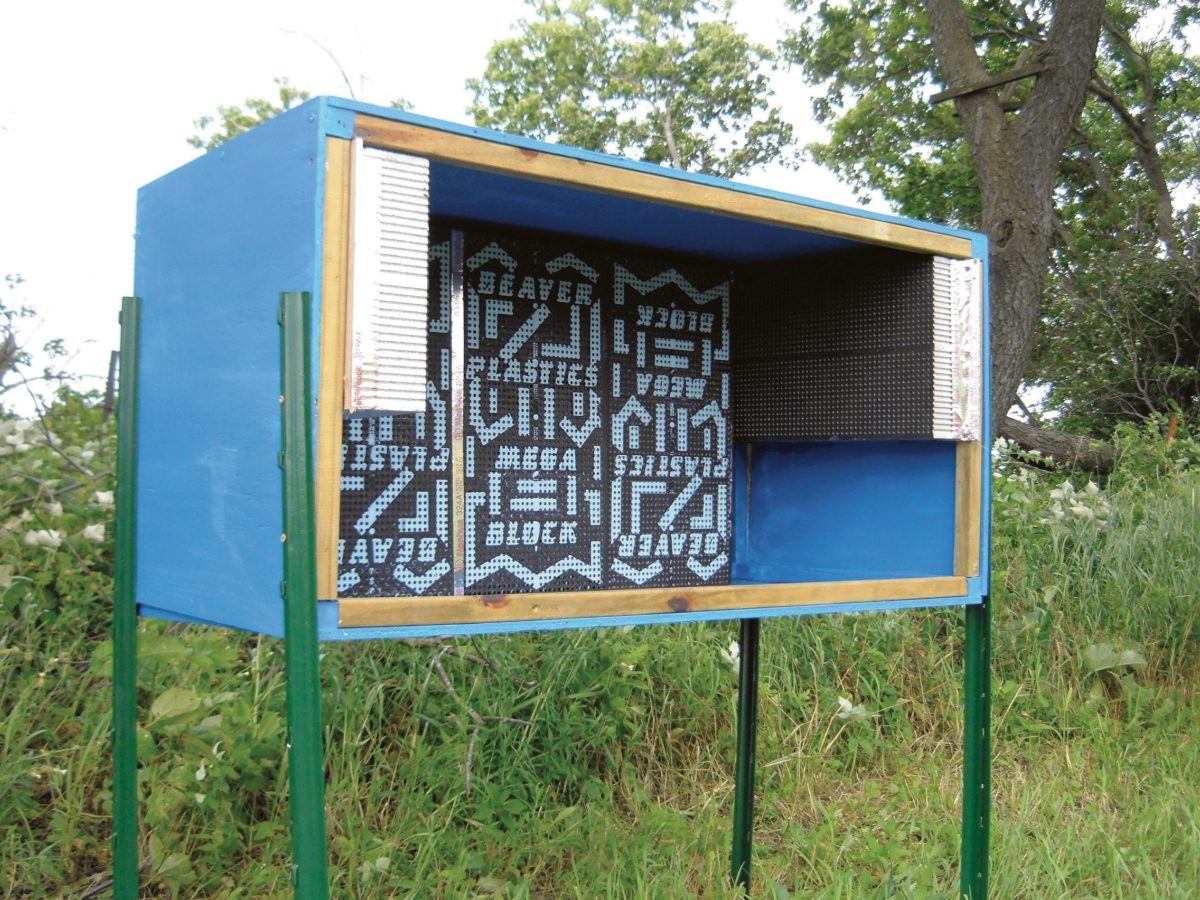

Bee nests are normally housed in field shelters for protection from rain, wind, and direct sunlight (Figure 7.16). As with nests, a great deal of research has been performed on various shelter designs, evaluating them on the basis of heat buildup, wind turbulence, and bee orientation among other factors. Like nests, the results of this research have sometimes been contradictory or inconclusive. One consistent factor has been identified, however: larger shelters provide a better orientation “landmark” for foraging bees than do small shelters. Freestanding leafcutter shelters used in the Canadian provinces are commonly 6 to 10 feet high, by 8 feet wide, and 4 feet deep (~1.8 to 3 meters high by 2.4 meters wide and 1.2 meters deep) (Figure 7.17). Deeper shelter designs are less attractive to bees especially if darker. Similarly, shelters should be painted in colors that contrast with the landscape. Contrasting vertical lines or other paint patterns may be helpful visual cues for returning bees.

If small shelters are used, they should be grouped together to form a landmark, or they should be placed against a barn wall or some other large structure. Conversely, an open barn or shed directly adjacent to the field can be used as a shelter with the nests hung inside the building.

Commercially produced leafcutter shelters are available from several Canadian manufacturers. These include tent-like shelters with metal frames and fabric sides, as well as molded plastic dome shelters (Figure 7.18). Many beekeepers construct their own plywood shelters as well, including elaborate mobile trailer-shelters that can be towed to and from the field.

Since foraging activity increases under high light intensity, shelters should face east or southeast if possible so that they capture sunlight early in the day. Direct sunlight, however, is not favorable and can result in overheating larvae inside finished nests. Similarly, shelters should also be sufficiently open on one side to allow for adequate air circulation, or they should be vented on top to prevent overheating. Temperatures higher than 90°F (32.2°C) can be lethal to developing bee larvae. Some producers allow loose cells to finish incubating in the field within the shelter. Beekeepers who do this often paint the roof of the shelter black to collect warmth, and hang the incubation trays just below the ceiling. Again care should be taken to prevent overheating.

Beekeepers that prefer to manage dormant bees inside nest blocks rather than as loose cells can leave the nests in the shelter year-round where the bees will develop and emerge naturally at ambient temperatures. However, if this is done, some sort of phaseout system should be employed to prevent bees from re-nesting in previously used nests. Such systems normally consist of a dark room or box within the shelter with a single exit hole. Bees (and parasites) are attracted to light entering the hole and will exit the phaseout chamber into the larger shelter where clean empty nests are installed. After the emergence period ends, the old nests can be removed from the phaseout chamber and cleaned. Shelters left in the field year-round should be loosely attached to ground anchors during the winter months to prevent damage from frost heaving.

Shelters may also need to be secured against predators. Ants and earwigs may be a common problem in leafcutter shelters. In freestanding shelters, they can be discouraged by coating the shelter legs with automotive grease. Woodpeckers, barn swallows, and other birds can become a nuisance in leafcutter operations. Birds can be excluded if necessary using plastic netting with the largest mesh size possible. The netting should be pulled tautly. Metal mesh should not be used as it can damage the bee’s wings. Since bees passing through netting often bump the mesh, causing them to drop leaf pieces during nest construction, netting should only be used as a last resort.

Wind can cause problems around bee shelters. Excessive wind turbulence around shelters can cause bees to drop leaf pieces as they approach the shelter. To combat this, some shelter designs feature walls extending out from the sides of the shelter, or vertical extensions above the shelter. These features also greatly increase wind resistance, and any shelter, with these extensions or not, should be firmly secured to the ground by attaching the legs to anchored metal fence posts. Guy wires may also be necessary.

Shelters and partially filled nests should not be moved during the nesting season. Any movement will result in disorientation for nesting bees and high numbers of bees drifting to other nesting sites.

There is some debate among beekeepers as to how many bees should be maintained per shelter and how many shelters are needed per field. Of course the final numbers are dependent on the particular crop, but leafcutter bees have a limited effective foraging range from the nest—probably not much more than 100 yards (~90 meters). At higher distances, bees tend to prefer nest sites closer to the forage source. Depending on the size of field to be pollinated, you may need to adjust the number and placement of shelters accordingly.

Finally, just because a shelter can accommodate a large number of nests doesn’t necessarily mean it should. There is some good evidence to suggest that shelter crowding results in fierce nest tunnel competition which stresses bees. This crowding may also translate into higher levels of chalkbrood and parasites. A minimum of two empty nest tunnels per female bee should be provided each season. More is better.