Hairy Vetch (Vicia villosa)

Type: winter annual or summer annual legume

Roles: N source, weed suppressor, topsoil conditioner, reduce erosion

Mix with: small grains, field peas, bell beans, crimson clover, buckwheat

See charts, p. 66 to 72, for ranking and management summary.

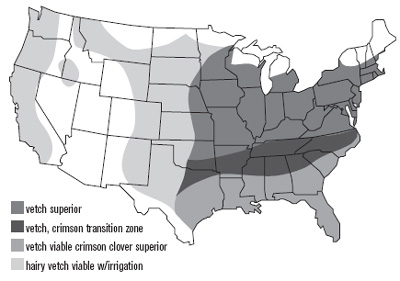

Few legumes match hairy vetch for spring residue production or nitrogen contribution. Widely adapted and winter hardy through Hardiness Zone 4 and into Zone 3 (with snow cover), hairy vetch is a top N provider in temperate and subtropical regions.

The cover grows slowly in fall, but root development continues over winter. Growth quickens in spring, when hairy vetch becomes a sprawling vine up to 12 feet long. Field height rarely exceeds 3 feet unless the vetch is supported by another crop. Its abundant, viney biomass can be a benefit and a challenge. The stand smothers spring weeds, however, and can help you replace all or most N fertilizer needs for late-planted crops.

Benefits of Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

Nitrogen source. Hairy vetch delivers heavy contributions of mineralized N (readily available to the following cash crop). It can provide sufficient N for many vegetable crops, partially replace N fertilizer for corn or cotton and increase cash crop N efficiency for higher yield.

In some parts of California and the East in Zone 6, hairy vetch provides its maximum N by safe corn planting dates. In Zone 7 areas of the Southeast, the fit is not quite as good, but substantial N from vetch is often available before corn planting.

Corn planting date comparison trials with cover crops in Maryland show that planting as late as May 15 (the very end of the month-long local planting period) optimizes corn yield and profit from the system. Spring soil moisture was higher under the vetch or a vetch-rye mixture than under cereal rye or no cover crop. Killed vetch left on the surface conserved summer moisture for improved corn production (80, 82, 84, 85, 173, 243).

Even without crediting its soil-improving benefits, hairy vetch increases N response and produces enough N to pay its way in many systems. Hairy vetch without fertilizer was the preferred option for “risk-averse” no-till corn farmers in Georgia, according to calculations comparing costs, production and markets during the study. The economic risk comparison included crimson clover, wheat and winter fallow. Profit was higher, but less predictable, if 50 pounds of N were added to the vetch system (310).

Note: To roughly estimate hairy vetch N contribution in pounds per acre, cut and weigh fresh vetch top growth from a 4-foot by 4-foot area. Multiply pounds of fresh vetch by 12 to gauge available N, by 24 to find total N (377). For a more accurate estimate, see How Much N?.

Hairy vetch ahead of no-till corn was also the preferred option for risk averse farmers in a three-year Maryland study that also included fallow and winter wheat ahead of the corn. The vetch-corn system maintained its economic advantage when the cost of vetch was projected at maximum historic levels, fertilizer N price was decreased, and the herbicide cost to control future volunteer vetch was factored in (173). In a related study on the Maryland Coastal Plain, hairy vetch proved to be the most profitable fall-planted, spring desiccated legume ahead of no-till corn, compared with Austrian winter peas and crimson clover (243).

In Wisconsin’s shorter growing season, hairy vetch planted after oat harvest provided a gross margin of $153/A in an oat/legume/corn rotation (1995 data). Profit was similar to using 160 lb. N/A in continuous corn, but with savings on fertilizer and corn rootworm insecticide (400).

Hairy vetch provides yield improvements beyond those attributable to N alone. These may be due to mulching effects, soil structure improvements leading to better moisture retention and crop root development, soil biological activity and/or enhanced insect populations just below and just above the soil surface.

Soil conditioner. Hairy vetch can improve root zone water recharge over winter by reducing runoff and allowing more water to penetrate the soil profile through macropores created by the crop residue (143). Adding grasses that take up a lot of water can reduce the amount of infiltration and reduce the risk of leaching in soils with excess nutrients. Hairy vetch, especially an oats/hairy vetch mix, decreased surface ponding and soil crusting in loam and sandy loam soils. Researchers attribute this to dual cover crop benefits: their ability to enhance the stability of soil aggregates (particles), and to decrease the likelihood that the aggregates will disintegrate in water (143).

Hairy vetch improves topsoil tilth, creating a loose and friable soil structure. Vetch doesn’t build up long-term soil organic matter due to its tendency to break down completely. Vetch is a succulent crop, with a relatively “low” carbon to nitrogen ratio. Its C:N ratio ranges from 8:1 to 15:1, expressed as parts of C for each part of N. Rye C:N ratios range from 25:1 to 55:1, showing why it persists much longer under similar conditions than does vetch. Residue with a C:N ratio of 25:1 or more tends to immobilize N. For more information, see How Much N?, and the rest of that section, Building Soil Fertility and Tilth with Cover Crops.

Early weed suppression. The vigorous spring growth of fall-seeded hairy vetch out-competes weeds, filling in where germination may be a bit spotty. Residue from killed hairy vetch has a weak allelopathic effect, but it smothers early weeds mostly by shading the soil. Its effectiveness wanes as it decomposes, falling off significantly after about three or four weeks. For optimal weed control with a hairy vetch mulch, select crops that form a quick canopy to compensate for the thinning mulch or use high-residue cultivators made to handle it.

Mixing rye and crimson clover with hairy vetch (seeding rates of 30, 10, and 20 lb./A, respectively) extends weed control to five or six weeks, about the same as an all-rye mulch. Even better, the mix provides a legume N boost, protects soil in fall and winter better than legumes, yet avoids the potential crop-suppressing effect of a pure rye mulch on some vegetables.

Good with grains. For greater control of winter annual weeds and longer-lasting residue, mix hairy vetch with winter cereal grains such as rye, wheat or oats.

Growing grain in a mixture with a legume not only lowers the overall C:N ratio of the combined residue compared with that of the grain, it may actually lower the C:N ratio of the small grain residue as well. This internal change causes the grain residue to break down faster, while accumulating the same levels of N as it did in a monoculture (344).

Moisture-thrifty. Hairy vetch is more drought tolerant than other vetches. It needs a bit of moisture to establish in fall and to resume vegetative growth in spring, but relatively little over winter when above-ground growth is minimal.

Phosphorus scavenger. Hairy vetch showed higher plant phosphorus (P) concentrations than crimson clover, red clover or a crimson/ryegrass mixture in a Texas trial. Soil under hairy vetch also had the lowest level of P remaining after growers applied high amounts of poultry litter prior to vegetable crops (121).

Fits many systems. Hairy vetch is ideal ahead of early-summer planted or transplanted crops, providing N and an organic mulch. Some Zone 5 Midwestern farmers with access to low-cost seed plant vetch after winter grain harvest in midsummer to produce whatever N it can until it winterkills or survives to regrow in spring.

Widely adapted. Its high N production, vigorous growth, tolerance of diverse soil conditions, low fertility need and winter hardiness make hairy vetch the most widely used of winter annual legumes.

Management of Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

Establishment & Fieldwork for Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

Hairy vetch can be no-tilled, drilled into a prepared seedbed or broadcast. Dry conditions often reduce germination of hairy vetch. Drill seed at 15 to 20 lb./A, broadcast 25 to 30 lb./A. Select a higher rate if you are seeding in spring, late in the fall, or into a weedy or sloped field. Irrigation will help germination, particularly if broadcast seeded.

Plant vetch 30 to 45 days before killing frost for winter annual management; in early spring for summer growth; or in July if you want to kill or incorporate it in fall or for a winter-killed mulch.

Hairy vetch has a relatively high P and K requirement and, like all legumes, needs sufficient sulfur and prefers a pH between 6.0 and 7.0. However, it can survive through a broad pH range of 5.0 to 7.5 (120).

An Illinois farmer successfully no-tills hairy vetch in late August at 22 lb./A into closely mowed stands of fescue on former Conservation Reserve Program land (417).Using a herbicide to kill the fescue is cheaper than mowing, but it must be done about a month later when the grass is actively growing for the chemical to be effective. Vetch also can be no-tilled into soybean or corn stubble (50, 80).

In Minnesota, vetch can be interseeded into sunflower or corn at last cultivation. Sunflower should have at least 4 expanded leaves or yield will be reduced (221, 222).

Farmers in the Northeast’s warmer areas plant vetch by mid-September to net 100 lb. available N/A by mid-May. Sown mid-August, an oats/hairy vetch mix can provide heavy residue (180).

Rye/hairy vetch mixtures mingle and moderate the effects of each crop. The result is a “hybrid” cover crop that takes up and holds excess soil nitrate, fixes N, stops erosion, smothers weeds in spring and on into summer if not incorporated, contributes a moderate amount of N over a longer period than vetch alone, and offsets the N limiting effects of rye (81, 83, 84, 86, 377).

Seed vetch/rye mixtures, at 15-25 lb. hairy vetch with 40-70 lb. rye/A (81, 361).

Overseeding (40 lb./A) at leaf-yellowing into soybeans can work if adequate rainfall and soil moisture are available prior to the onset of freezing weather. Overseeding into ripening corn (40 lb./A) or seeding at layby has not worked as consistently. Late overseeding into vegetables is possible, but remember that hairy vetch will not stand heavy traffic (361).

Cover Crop Roller Design Holds Promise For No-Tillers

However, timing of control and planting in a single pass could limit adoption; hope lies in breeding cover crops that flower in time for traditional planting window.

THE POSSIBILITY of using rollers to reduce herbicide use isn’t new, but advances are being made to improve the machines in ways that could make them practical for controlling no-till cover crops.

Cover crop rolling is gaining visibility and credibility in tests by eight university/farmer research teams across the country. The test rollers were designed and contributed by The Rodale Institute (TRI), a Pennsylvania -based organization focused on organic agricultural research and education. The control achieved with the roller is comparable to a roller combined with a glyphosate application, according to TRI.

The Rodale crop rollers were delivered to state and federal cooperative research teams in Virginia, Michigan, Mississippi, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Georgia, California and Iowa in Spring, 2005. Funding for the program comes from grants and contributions from the Natural Resources Conservation Service and private donors. I&J Manufacturing in Gap, Pa., fabricated the models distributed to the research teams.

“The requirement is that each research leader partners with a farmer cooperator to adapt the rollers to local conditions and cover cropping systems,” explains Jeff Moyer, TRI’s farm manager. “Our goal is to gain more knowledge about the soil building and weed management effects of cover crops while reducing the need for herbicides,” he says.

Farmer Built. Moyer designed and built the first front-mounted TRI roller prototype in 2002 in conjunction with Pennsylvania farmer John Brubaker, whose land abuts the TRI property. The original 10-foot, 6-inch roller width is equal to 4 rows on 30-inch spacing, with a 3-inch overlap on each end. The original design has already been modified to include a 15-foot, 6-inch model suitable for use with a 6- row planter on 30-inch rows. It can be adapted to fit a 4-row planter on 38-inch rows, and a 5- foot version for 2-row vegetable planters.

“We realize that 6-row equipment is small by today’s standards, and work is under way on a system that mounts one section of the roller in front of the tractor with the remainder mounted on the planter ahead of the row units. This design will allow as wide a roller system as a farmer needs,” Moyer says.

Chevron Pattern. The chevron pattern on the face of the roller came about after the designers realized that mounting the roller blades in a straight line would cause excessive bouncing, while just curving the blades in a screw pattern would act like an auger and create a pulling effect. “If you were driving up a hill that might be fine, but we don’t need help pulling our tractors down the steep slopes we farm. The chevron pattern neutralizes any forces that might pull the tractor in either direction,” Moyer explains. It overcomes both the bounce of straight-line blades and the auguring effect of corkscrew blades.

“In addition, with the twisted blade design, only a very small portion of the blade touches the ground at any one time as it turns, so the full pressure of the roller is applied 1 inch at a time. This roller design works better than anything we’ve ever used,” he adds.

Prior to settling on the TRI prototype, Moyer and Brubaker studied stalk choppers with nine rolling drums arranged in two parallel rows. This design required 18 bearings and provided lots of places for green plant material to bunch up. The TRI ground-driven roller has a single cylinder and two offset bearings inset 3 inches on either side and fronted with a shield. The blades are welded onto the 16-inch-diameter drum, but replacement blades can be purchased from the manufacturer and bolted on as needed. The 10-foot, 6-inch roller weighs 1,200 pounds empty and 2,000 pounds if filled with water.

Front Mount Benefits. The biggest advantage of the front-mounted roller is that the operator can roll the cover crop and no-till the cash crop in a single field pass, Moyer explains. In TRI trials, simultaneous rolling and no-till planting eliminated seven of the eight field passes usually necessary with conventional organic corn production, including plowing, discing, packing, planting, two rotary hoe passes and two cultivations.

Rolling the field and no-tilling in one pass also eliminates the problem of creating a thick green cover crop mat that makes it difficult to see a row marker line on a second pass for planting.

Also, planting in a second pass in the opposite direction from which the cover crop was rolled makes getting uniform seeding depth and spacing more difficult because the planter tends to stand the plant material back up. “Think of it as combing the hair on your dog backwards,” Moyer says.

“Another disadvantage of rear-mounted machines like stalk choppers is that the tractor tire is the first thing touching the cover crop. If the soil is even a little spongy, the cover crop will be pushed into the tire tracks and because the roller is running flat, it can’t crimp the depressed plant material. A week later the plants missed by the roller will be back up and growing again.”

Crop Versatility. The TRI roller concept has been tested in a wide range of winter annual cover crops, including cereal rye, hairy vetch, wheat, triticale, oats, buckwheat, clover, winter peas and other species. Timing is the key to success, Moyer emphasizes, and a lot of farmers don’t have the patience to make it work right.

“The bottom line is that winter annuals want to die anyway, but if you time it wrong, they’re hard to kill,” he says. “If you try to roll a winter annual before it has flowered—before it has physiologically reproduced—the plant will try to stand up again and complete the job of reproduction, the most important stage of its life cycle. But, if you roll it after it has flowered, it will dry up and die.”

At least a 50 percent, and preferably a 75 to 100 percent bloom, is recommended before rolling. Moyer hopes to see plant breeders recognize the need to develop cover crop varieties with blooming characteristics that coincide with preferred crop planting windows.

“We really like to use hairy vetch on our farm, for example, because it’s a great source of nitrogen and is a very suitable crop to plant corn into. The roller crimps the stem of the hairy vetch every 7 inches, closing the plant’s vascular system and ensuring its demise.

“The problem is we would like it to flower a couple weeks earlier to fit our growing season. It’s hard for farmers to understand when it’s planting time and we’re telling them to wait a couple more weeks for their cover crop to flower,” he says.

“We need to identify the characteristics we want in cover crops and encourage plant breeders to focus on some of those. It should be a relatively easy task to get an annual crop to mature a couple weeks earlier, compared to some of the breakthrough plant breeding we’ve seen recently,” Moyer says.

For More Information. Updates on roller research, more farmer stories and plans for the TRI no-till cover crop roller can be accessed at www.newfarm.org/depts/no-till. To ask questions of The Rodale Institute, e-mail to info@rodaleinst.org.

See also “Where can I find information about the mechanical roller-crimper used in no-till production?” https://attra .ncat.org/calendar/question.php/2006/05/08/p2221.

To contact the manufacturer of commercially available cover crop rollers, visit www.croproller.com.

Editor’s Note: PURPLE BOUNTY, a new, earlier variety of hairy vetch, was released in 2006 by the USDA -Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, MD in collaboration with the Rodale Institute, Pennsylvania State University and Cornell University.

—Ron Ross. Adapted with permission from www.no-tillfarmer.com

Killing Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

Your mode of killing hairy vetch and managing residue will depend on which of its benefits are most important to you. Incorporation of hairy vetch vegetation favors first-year N contribution, but takes significant energy and labor. Keeping vetch residue on the surface favors weed suppression, moisture retention, and insect habitat, but may reduce N contribution. However, even in no-till systems, hairy vetch consistently provides very large N input (replacing up to 100 lb. N/A).

In spring, hairy vetch continues to add N through its “seed set” stage after blooming. Biomass and N increase until maturity, giving either greater benefit or a dilemma, depending on your ability to deal with vines that become more sprawling and matted as they mature.

Mulch-retaining options include strip-tilling or strip chemical desiccation (leaving vetch untreated between the strips), mechanical killing (rotary mowing, flailing, cutting, sub-soil shearing with an undercutter, or chopping/flattening with a roller/crimper) or broadcast herbicide application.

No-till corn into killed vetch. The best time for no-till corn planting into hairy vetch varies with local rainfall patterns, soil type, desired N contribution, season length and vetch maturity.

In southern Illinois, hairy vetch no-tilled into fescue provided 40 to 180 lb. N/A per year over 15 years for one researcher/farmer. He used herbicide to kill the vetch about two weeks before the area’s traditional mid-May corn planting date. The 14-day interval was critical to rid the field of prairie voles, present due to the field’s thick fescue thatch.

He kills the vetch when it is in its pre-bloom or bloom stage, nearing its peak N-accumulation capacity. Further delay would risk loss of soil moisture in the dry period customary there in early June. When the no-tilled vetch was left to grow one season until seed set, it produced 6 tons of dry matter and contributed a potentially polluting 385 lb. N/A (417). This high dose of N must be managed carefully during the next year to prevent leaching or surface runoff of nitrates.

A series of trials in Maryland showed a different mix of conditions. Corn planting in late-April is common there, but early killing of vetch to plant corn then had the surprising effect of decreasing soil moisture and corn yield, as well as predictably lowering N contribution. The earlier planted corn had less moisture-conserving residue. Late April or early May kill dates, with corn no-tilled 10 days later, consistently resulted in higher corn yields than earlier kill dates (82, 83, 84, 85). With hairy vetch and a vetch/rye mixture, summer soil water conservation by the cover crop residue had a greater impact than spring moisture depletion by the growing cover crop in determining corn yield (84, 85).

Results in the other trials, which also included a pure rye cover, demonstrated the management flexibility of a legume/grain mix. Early killed rye protects the soil as it conserves water and N, while vetch killed late can meet a large part of the N requirement for corn. The vetch/rye mixture can conserve N and soil moisture while fixing N for the subsequent crop. The vetch and vetch/rye mixture accumulated N at 130 to 180 lb./A. The mixture contained as much N or more than vetch alone (85, 86).

In an Ohio trial, corn no-tilled into hairy vetch at mid-bloom in May received better early season weed control from vetch mulch than corn seeded into vetch killed earlier. The late planting date decreased yield, however (189), requiring calculation to determine if lower costs for tillage, weed control, and N outweigh the yield loss.

Once vetch reaches about 50% bloom, it is easily killed by any mechanical treatment. To mow-kill for mulch, rye grown with hairy vetch improves cutting by holding the vetch off the ground to allow more complete severing of stems from roots. Rye also increases the density of residue covering the vetch stubble to prevent regrowth.

Much quicker and more energy-efficient than mowing is use of a modified Buffalo rolling stalk chopper, an implement designed to shatter standing corn stubble. The chopper’s rolling blades break over, crimp and cut crop stems at ground level, and handle thick residue of hairy vetch at 8 to 10 mph (169).

No-till vegetable transplanting. Vetch that is suppressed or killed without disturbing the soil maintains moisture well for transplanted vegetables. No-till innovator Steve Groff of Lancaster County, PA,, uses the rolling stalk chopper to create a killed organic mulch. His favorite mix is 25 lb. hairy vetch, 30 lb. rye and 10 lb. crimson clover/A.

No-till, delayed kill. Farmers and researchers are increasingly using a roller/crimper to kill hairy vetch and other cover crops (11). Jeff Moyer and others at the Rodale Institute in Kutztown, Pa ., roll hairy vetch and other cover crops in late May or early June (at about 50% flower). The modified roller is front-mounted, and corn is no-tilled on the same pass (303). See Cover Crop Roller Design Holds Promise For No-Tillers.

Also useful in killing hairy vetch on raised beds for vegetables and cotton is the improved prototype of an undercutter that leaves severed residue virtually undisturbed on the surface (96). The undercutter tool includes a flat roller attachment, which, by itself, usually provides only partial suppression unless used after flowering.

Herbicides will kill vetch in three to 30 days, depending on the material used, rate, growth stage and weather conditions.

Vetch incorporation. As a rule, to gauge the optimum hairy vetch kill date, credit vetch with adding two to three pounds of N per acre per sunny day after full spring growth begins. Usually, N contribution will be maximized by early bloom (10-25 percent) stage.

Cutting hairy vetch close to the ground at full bloom stage usually will kill it. However, waiting this long means it will have maximum top growth, and the tangled mass of mature vetch can overwhelm many smaller mowers or disks. Flail mowing before tillage helps, but that is a time and horsepower intensive process. Sickle-bar mowers should only be used when the vetch is well supported by a cereal companion crop and the material is dry (422).

Management Cautions for Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

About 10 to 20 percent of vetch seed is “hard” seed that lays ungerminated in the soil for one or more seasons. This can cause a weed problem, especially in winter grains. In wheat, a variety of herbicides are available, depending on crop growth stage. After a corn crop that can utilize the vetch-produced N, you could establish a hay or pasture crop for several years.

Don’t plant hairy vetch with a winter grain if you want to harvest grain for feed or sale. Production is difficult because vetch vines will pull down all but the strongest stalks. Grain contamination also is likely if the vetch goes to seed before grain harvest. Vetch seed is about the same size as wheat and barley kernels, making it hard and expensive to separate during seed cleaning (361). Grain price can be markedly reduced by only a few vetch seeds per bushel.

A severe freeze with temperatures less than 5° F may kill hairy vetch if there is no snow cover, reducing or eliminating the stand and most of its N value. If winterkill is possible in your area, planting vetch with a hardy grain such as rye ensures spring soil protection.

Pest Management for Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

In legume comparison trials, hairy vetch usually hosts numerous small insects and soil organisms (206). Many are beneficial to crop production, (see below) but others are pests. Soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines) and root-knot nematode (Meliodogyne spp.) sometimes increase under hairy vetch. If you suspect that a field has nematodes, carefully sample the soil after hairy vetch. If the pests reach an economic threshold, plant nematode-resistant crops and consider using another cover crop.

Other pests include cutworms (361) and southern corn rootworm (67), which can be problems in no-till corn, tarnished plant bug, noted in coastal Massachusetts (56), which readily disperses to other crops, and two-spotted spider mites in Oregon pear orchards (142). Leaving unmowed remnant strips can lessen movement of disruptive pests while still allowing you to kill most of the cover crop (56).

Prominent among beneficial predators associated with hairy vetch are lady beetles, seven-spotted ladybeetles (56) and bigeyed bugs (Geocaris spp.). Vetch harbors pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum) and blue alfalfa aphids (Acyrthosiphon kondoi) that do not attack pecans but provide a food source for aphid-eating insects that can disperse into pecans (58). Similarly, hairy vetch blossoms harbor flower thrips (Frankliniella spp.), which in turn attract important thrip predators such as insidious flower bugs (Orius insidiosus) and minute pirate bugs (Orius tristicolor).

Two insects may reduce hairy vetch seed yield in heavy infestations: the vetch weevil or vetch bruchid. Rotate crops to alleviate buildup of these pests (361).

Hairy Vetch Cover Crops Beat Plastic

BELTSVILLE, MD.—Killed cover crop mulches can deliver multiple benefits for no-till vegetable crops (1, 2, 3, 4). The system can provide its own N, quell erosion and leaching, and displace herbicides. It’s also more profitable than conventional commercial production using black plastic mulch. A budget analysis showed it also should be the first choice of “risk averse” farmers, who prefer certain although more modest profit over higher average profit that is less certain (224).

The key to the economic certainty of a successful hairy vetch planting is its low cost compared with the black plastic purchase, installation and removal.

From refining his own research and on-farm tests in the mid-Atlantic region for several years, Aref Abdul-Baki, formerly of the USDA ’s Beltsville (Md.) Agricultural Research Center, outlines his approach:

- Prepare beds—just as you would for planting tomatoes—at your prime time to seed hairy vetch.

- Drill hairy vetch at 40 lb./A, and expect about 4 inches of top growth before dormancy, which stretches from mid- December to mid-March in Maryland.

- After two months’ spring growth, flail mow or use other mechanical means to suppress the hairy vetch. Be ready to remow or use herbicides to clean up trouble spots where hairy vetch regrows or weeds appear.

- Transplant seedlings using a minimum tillage planter able to cut through the mulch and firm soil around the plants.

The hairy vetch mulch suppresses early season weeds. It improves tomato health by preventing soil splashing onto the plants, and keeps tomatoes from soil contact, improving quality. Hairy vetch-mulched plants may need more water. Their growth is more vigorous and may yield up to 20 percent more than those on plastic. Completing harvest by mid- September allows the field to be immediately reseeded to hairy vetch. Waiting for vetch to bloom in spring before killing it and the tight fall turnaround may make this system less useful in areas with a shorter growing season than this Zone 7, mid-Atlantic site.

Abdul-Baki rotates season-long cash crops of tomatoes, peppers and cantaloupe through the same plot between fall hairy vetch seedings. He shallow plows the third year after cantaloupe harvest and seeds hairy vetch for flat-field crops of sweet corn or snap beans the following summer.

He suggests seeding rye (40 lb./A) with the vetch for greater biomass and longer-lasting mulch. Adding 10-12 lb./A of crimson clover will aid in weed suppression and N value. Rolling the covers before planting provides longer-lasting residue than does mowing them. Some weeds, particularly perennial or winter annual weeds, can still escape this mixture, and may require additional management (4).

Crop Systems for Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

In no-till systems, killed hairy vetch creates a short-term but effective spring/summer mulch, especially for transplants. The mulch retains moisture, allowing plants to use mineralized nutrients better than unmulched fields. The management challenge is that the mulch also lowers soil temperature, which may delay early season growth (361). One option is to capitalize on high quality, low-cost tomatoes that capture the late-season market premiums. See Vetch Beats Plastic.

How you kill hairy vetch influences its ability to suppress weeds. Durability and effectiveness as a lightblocking mulch are greatest where the stalks are left whole. Hairy vetch severed at the roots or sickle-bar mowed lasts longer and blocks more light than flailed vetch, preventing more weed seeds from germinating (96, 411).

Note: An unmowed rye/hairy vetch mix sustained a population of aphid-eating predators that was six times that of the unmowed volunteer weeds and 87 times that of mown grass and weeds (57).

Southern farmers can use an overwintering hairy vetch crop in continuous no-till cotton. Vetch mixed with rye has provided similar or even increased yields compared with systems that include conventional tillage, winter fallow weed cover and up to 60 pounds of N fertilizer per acre. Typically, the cover crops are no-till drilled after shredding cotton stalks in late October. Covers are spray killed in mid-April ahead of cotton planting in May. With the relatively late fall planting, hairy vetch delivers only part of its potential N in this system. It adds cost, but supplies erosion control and long-term soil improvement (35).

Cotton yields following incorporated hairy vetch were perennial winners for 35 years at a northwestern Louisiana USDA site. Soil organic matter improvement and erosion control were additional benefits (276).

Other Options for Hairy Vetch Cover Crops

Spring sowing is possible, but less desirable than fall establishment because it yields significantly less biomass than overwintering stands. Hot weather causes plants to languish.

Hairy vetch makes only fair grazing—livestock do not relish it.

Harvesting seed. Plant hairy vetch with grains if you intend to harvest the vetch for seed. Use a moderate seeding rate of 10-20 lb./A to keep the stand from getting too rank. Vetch seed pods will grow above the twining vetch vines and use the grain as a trellis, allowing you to run the cutter bar higher to reduce plugging of the combine. Direct combine at mid-bloom to minimize shattering, or swath up to a week later. Seed is viable for at least five years if properly stored (361).

If you want to save dollars by growing your own seed, be aware that the mature pods shatter easily, increasing the risk of volunteer weeds. To keep vetch with its nurse crop, harvest vetch with a winter cereal and keep seed co-mingled for planting. Check the mix carefully for weed seeds.

Comparative Notes

Hairy vetch is better adapted to sandy soils than crimson clover (344), but is less heat-tolerant than LANA woollypod vetch. See Woollypod Vetch.

Cultivars. MADISON—developed in Nebraska — tolerates cold better than other varieties. Hairy vetches produced in Oregon and California tend to be heat tolerant. This has resulted in two apparent types, both usually sold as “common” or “variety not stated” (VNS). One has noticeably hairy, bluish-green foliage with bluish flowers and is more cold-tolerant. The other type has smoother, deep-green foliage and pink to violet flowers.

A closely related species—LANA woollypod vetch (Vicia dasycarpa)—was developed in Oregon and is less cold tolerant than Vicia villosa. Trials in southeastern Pennsylvania with many accessions of hairy vetch showed big flower vetch (Vicia grandiflora, cv WOODFORD) was the only vetch species hardier than hairy vetch. EARLY COVER hairy vetch is about 10 days earlier than regular common seed. PURPLE BOUNTY, released in 2006, is a few days earlier and provides more biomass and better ground cover than EARLY COVER.