Download all planning task four worksheets using the link above.

In this task, you will create business strategies for transitioning and certifying your farm. Strategies form the core of your business plan and address questions about how you will get from here (pre-transition) to there (organic certification). We will provide strategy examples throughout this planning task, but remember that the strategies you develop should be unique to your own resources, goals and mission.

Planning Task Four addresses the following sections of your business plan:

Operations

- Production opportunities

- Operations strategy

- Licenses and organic certification

- Resource needs and acquisition

- Operations risk management

Marketing

- Marketing opportunities

- Marketing strategy

- Licenses and organic certification

- Marketing risk management

Human Resources

- Human resource opportunities

- Planning and management team

- Licenses and safety regulations

- Human resource strategy

- Human resource risk management

Finances

- Financial opportunities

- Financial strategy

- Financial projections

- Capital requests

- Financial risk management

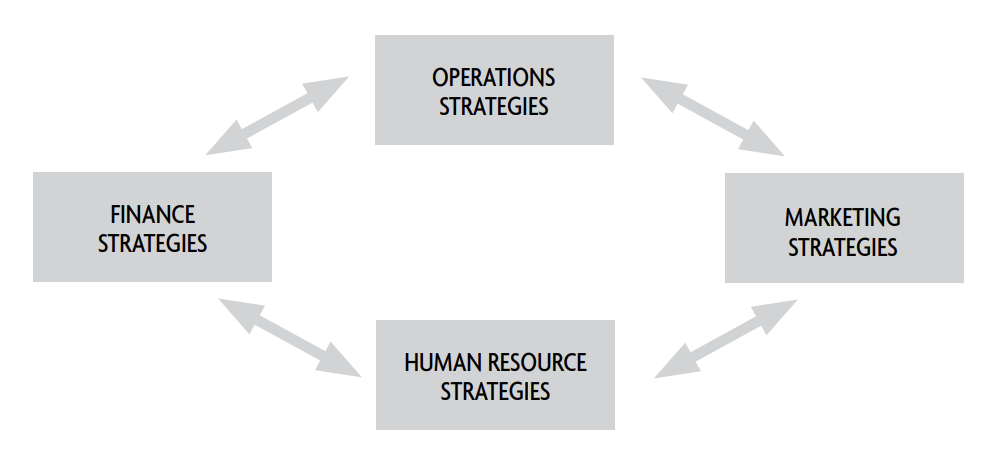

You may find that as you complete research and develop strategies for one section of your plan, marketing for example, it may impact or necessitate changes to strategies in other sections of the plan, for example operations. Strategy development is an iterative process calling for you to revisit and refine as you go.

OPERATIONS

We suggest that you begin this planning task by developing one or two big picture, or whole-farm, strategies. Whole-farm strategies serve as a good reminder of how you intend to accomplish goals and can be used as a starting point from which to generate specific op-erations, marketing, human resource and finance strategies. They also serve as a commu-nicator for your business overview in the written plan—describing how and when you will transition as well as your rationale for doing so. Use Worksheet 4T.1: Whole-Farm Strategies to record your whole-farm strategy. Examples of whole-farm strategies are provided in the story panels.

whole-farm strategy

Gradually transition land, then transition cows in third year. Strategy Rationale: Work through organic learning curve, supply feed needs from farm and gradually identify management opportunities for son.

Purchase organic vegetables for processing into naturally fermented, ethnic products targeted at Russian-speaking communities while transitioning land and developing production capacity. Strategy Rationale: Develop recipes and markets using purchased inputs while learning to grow my own organic vegetables for processing.

OPERATIONS - Production Opportunities

It is important to identify production opportunities, as they can steer your strategy decisions and help convince partners and investors that your idea is grounded in real prospects.

Brainstorm short- and long-term production opportunities that may be unique to your operation or are characteristic of changes in the agriculture sector as a whole. The most compelling opportunities will be those that are unique to your farm business. Some of the opportunities recorded by farmers participating in the Tools for Organic Transition Project included the option of renting certified land from a neighbor, the ability to grow a particular commodity due to soil type and the availability of a certified dairy herd. Additional examples of operational opportunities are depicted in the story panels.

Operational opportunities

My neighbor has offered to sell me organic feed during transition at a discounted price. This will allow me to meet livestock feed needs while showing a positive cash flow. I will have to repay my neighbor for the difference between the discounted rate and going organic rate once I am certified.

This plan focuses on the opportunity to gain stable, continuous access to land in 2016 through a five-year lease with a right of first refusal to purchase the land at the end of the lease. We assume the land we rent will have been in conventional production through 2015 and so will need to be transitioned.

BJF has many production opportunities in the coming year. These include the short-term use of Rutgers Commercial Kitchen lab to experiment with recipes and processing; use of one neighbor’s greenhouse to start seedlings; and rental of two acres of another neighbor’s certifiable land. A longer-term production opportunity is the expansion of BJF to include 30 acres of nearby land that is expected to come up for sale within the next few years, if needed.

Space is provided on Worksheet 4T.2: Operations Strategy Summary to draft concise, positive statements describing production opportunities. Support any opportunities with research and written commitments if possible.

OPERATIONS - Operations Strategy

You have dreamed about the future, outlined goals, inventoried resources and explored opportunities associated with going organic. Now, it is time to develop your operations strategy; to identify how you will make it all happen. Your operations strategy should brief-ly address the following items (many of which can be used for your OSP or OSPH):

- Crop and livestock production activities

- Value-added processing

- Land, facilities, equipment and other input needs

- Feed requirements

- Production estimates

- Inventory management and quality control

Begin your operations strategy development by reviewing the basics of organic production management. See Text Box: The National Organic Program and Certification Basics.

Operations Strategy

This plan assumes that in 2015 we will initiate transition on 82 acres currently under conventional production and rent an additional 20 acres of adjacent land coming out

of CRP that can be certified immediately. In 2016 we will rent a farm with 480 acres of tillable land that has been under conventional management.

Once you are ready, brainstorm short-term (transition, the first three years) and long-term (post-certification, years four and five) operations and processing strategies.

A common strategy is to run a split operation in which a portion of the farm or processing is managed organically and the remainder is managed conventionally. Some farmers and educators advocate initially transitioning only a small amount of farm acreage—that with the best soil quality, moisture levels and pest control—while managing the remainder of the farm conventionally. Once the initial parcel of land is certified and market premiums are available, then you would transition the remainder of your farmland. This strategy has benefits, such as the ability to learn as you go on limited acreage. However, this strategy also will require that you invest time and, sometimes, money in services and equipment to prevent commingling and contamination of crops and products at all stages, from planting to the final sale.

Or, like the Kerkaerts, your plan might include transitioning land under long-term lease as you build skills and assets before purchasing your own land that you will certify. See their operations strategy in the story panel.

Processors, too, often use a split-operation strategy. They will dedicate one day per week or the first processing run of the day to certified organic products. They then process several runs or batches as conventional, and clean out all equipment before switching to the next organic run.

Another management strategy is to transition everything at once—all of your land, live-stock or processing. This “all in” strategy can make planning, management and record-keeping simpler. The drawback to this strategy, however, is that it exposes you to greater yield and price risk by forcing you to experiment with everything at once.

Record your operations strategy ideas on Worksheet 4T.2: Operations Strategy Summary in the strategy description section at the top of the worksheet. You will complete the remainder of the worksheet later.

Regardless of whether you transition all or some of your land, carefully consider the timing of planned operations. For example, if you currently produce field crops or fruits and vegetables, time your input applications (seed, pesticide and fertilizer) so that it is possible to certify in the third year just before harvest. This will allow you to capture market premiums in the third year of transition rather than having to wait until your fourth-year harvest. Likewise, if you are a livestock producer with field crops, consider transitioning your cropland for two years before beginning to transition animals. This will allow you to certify land and animals simultaneously. If you were to transition animals first, before your land was certified, you would be required to purchase expensive organic feed and obtain access to certified pasture. See Figure 4T.2: National Organic Program Livestock Standards for more information about feed requirements.

Figure 4T.2: National Organic Program Livestock Standards.

National Organic Program Livestock Standards

Ruminant animals must be grazed throughout the entire grazing season for the geographical region, which shall be not less than 120 days per calendar year. Due to weather, season, and/or climate, the grazing season may or may not be continuous. … All ruminants under the organic system plan [must be provided] with an average of not less than 30 percent of their dry matter intake from grazing throughout the grazing season.

Crop and Livestock Activities

After settling on one or more general production strategies, brainstorm crop and livestock enterprises to include in your rotation as well as any conditions that might affect rotation plans (such as livestock feed requirements). Be sure to review the NOP regulations on crop rotation presented in Figure 4T.3: National Organic Program Crop Rotation Standards and check out the story panel to see the Kerkaerts’ crop rotation strategy. When ready, record your crop production plans for transition and certification on Worksheet 4T.3: Crop and Livestock Enterprises.

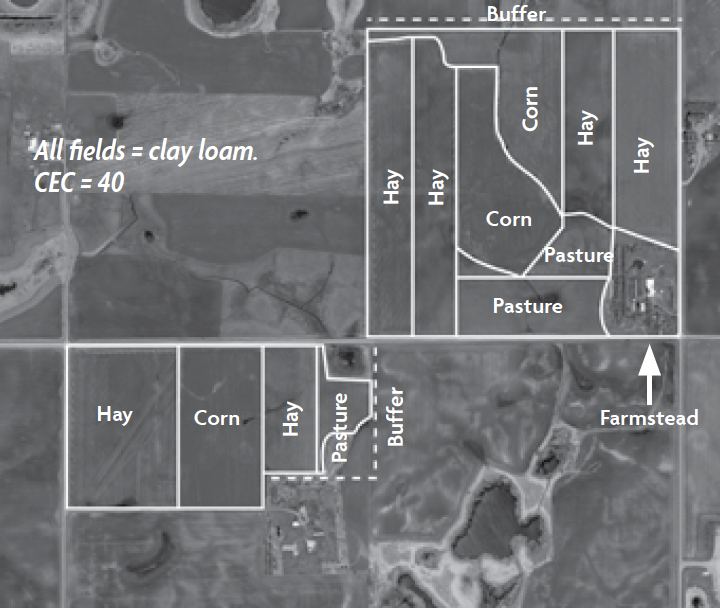

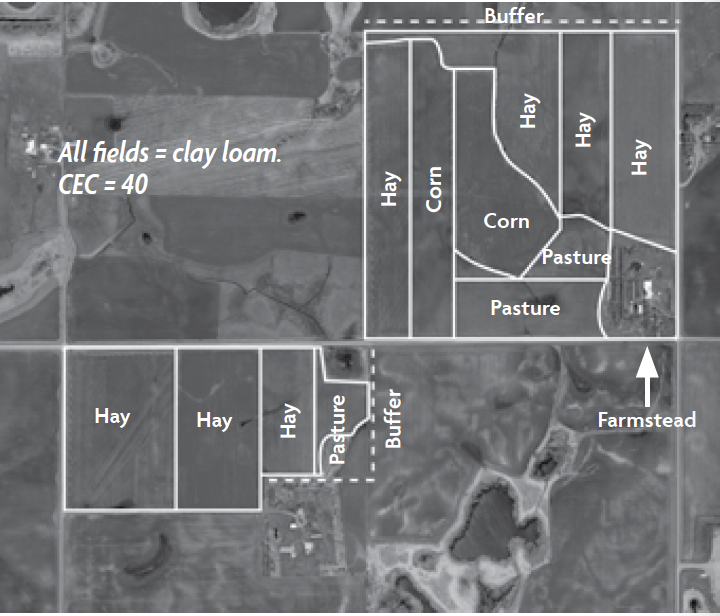

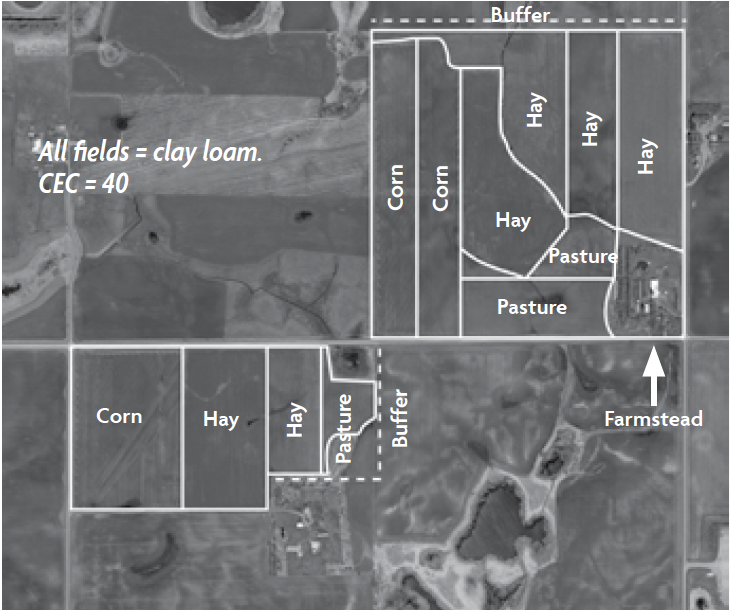

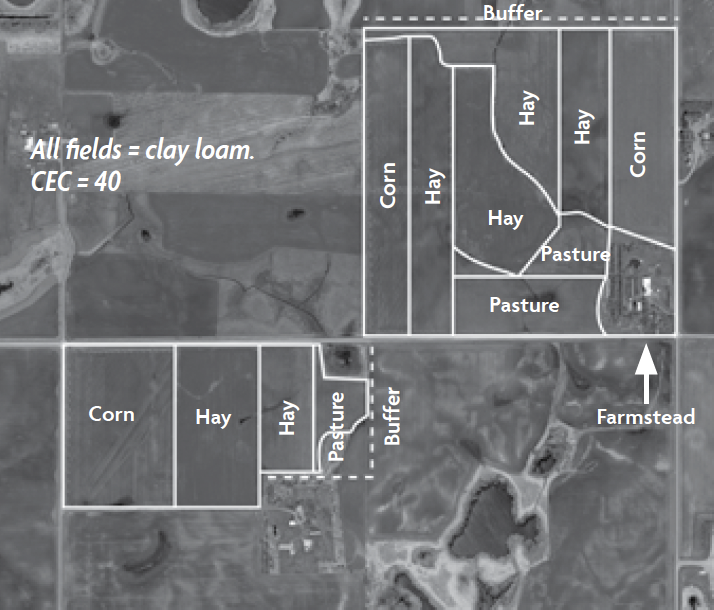

Next, using the list of potential enterprises, create multi-year field maps reflecting crop rotations or grazing schedules. This exercise is similar to the one you did in Planning Task Two: Current Situation, only now you are mapping the future. Use Worksheet 4T.4: Transitional Farm Map or a blank piece of paper to create a map for each year in your rotation, if you are growing crops. For transitional cropping maps, depict buffers, conservation acreage, permanent vegetation, orchards, woodlands and buildings. If your operation includes livestock, note your fencing, watering lines, housing and grazing schedules. You should also include field notes about soil types as well as pest, weed and disease management practices, which you can base on soil tests and the inventory work that you did in Planning Task Two: Current Situation. Also, include any expected changes in herd size and pasture management. If you are growing fruits and vegetables that allow for succes-sion planting, we suggest that you create seasonal rather than yearly maps. All of the information that you record here can be used in your OSP. Look at Figure 4T.4: Transition and Certification Farm Maps, Walter, 2011-2014 to see how the Walter family plotted their crop rotation when planning their transition.

Figure 4T.3: National Organic Program Crop Rotation Standards

National Organic Program Crop Rotation Practice Standards

The producer must implement a crop rotation including but not limited to sod, cover crops, green manure crops and catch crops that provide the following functions that are applicable to the operation:

(a) Maintain or improve soil organic matter content;

(b) Provide for pest management in annual and perennial crops;

(c) Manage deficient or excess plant nutrients; and

(d) Provide erosion control.

Figure 4T.4: Transition and Certification Farm Maps, Walter 2011-2014.

Processed Products and Services

Processing Defined

Processing is defined by the USDA as: cooking, baking, curing, heating, drying, mixing, grinding, churning, separating, extracting, slaughtering, cutting, fermenting, distilling, eviscerating, preserving, dehydrating, freezing, chilling or otherwise manufacturing, and includes packaging, canning, jarring or otherwise enclosing food in a container.

Source: Do I Need To Be Certified Organic? June 2012. National Organic Program, Agricultural Marketing Service, USDA.

If you plan to offer services or add value through any type of processing (see Text Box 4T.1: Processing Defined for the USDA’s definition of processing), you have more planning and mapping to do!

For example, processed products that are intended for sale as certified organic must be handled in a certified facility (NOP § 205.100 and § 205.101) and are subject to packaging and labeling requirements. We will get you started here, but strongly recommend reading the Guide for Organic Processors by Pamela Coleman. This publication, listed in the Resources section, is a great place to begin your strategy research if you plan to process and certify organic.

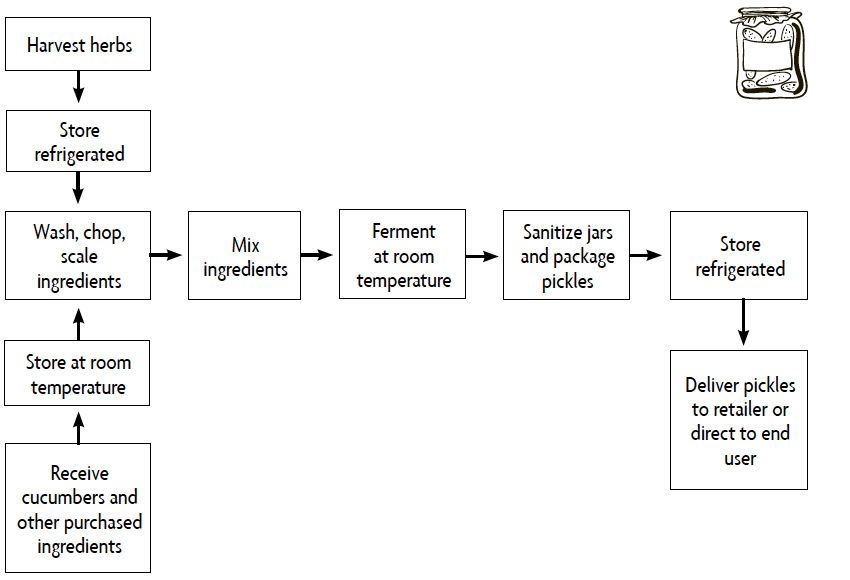

One of the first things you will need to consider when developing a processing strategy is how you will process. Use Worksheet 4T.5: Organic Processing Map to create a processing flow chart and facility map. These are much like field maps in that they visually describe where you will process and how you will process. Flow charts and facility maps are required for an OSPH and typically include building dimensions, processing stations (e.g., washing, cutting, cooking, packing, etc.), equipment, bathroom(s), and storage and distribution areas. See the BJF flow chart in Figure 4T.5: BJF Flow Chart for an example and note that it is a bit rudimentary. Like BJF owner Vitaly Brukhman, you can add more detail as you continue to explore processing strategies.

Processed Products

BJF will eventually process and sell a range of naturally fermented foods and drinks as well as jams, sauces, dressings and frozen soups. We will begin with the following naturally fermented products:

- Pickles

- Sauerkraut

- Tomatoes

- Kvass

- Kombucha

- Ginger ale

- Pickle juice

- Stringing nettle juice

All of these products can be processed using much of the same inputs, equipment and facilities, so it will be fairly easy to add any of the above foods and drinks to the BJF product line as business grows.

Next, use Worksheet 4T.6: Processed Products and Services to list products and services that you would like to produce and certify. Use the same worksheet to describe the type of processing required for each value-added product or service (e.g., dehydration, fermentation, baking). If known, record the location of processing facilities and options for establishing processing and service-related infrastructure on the farm. For an example, see Vitaly Brukhman’s story panel on processed products.

Land, Facilities, Equipment and Input

When beginning to transition, 72 percent of farmers purchased new equipment, 28 percent hired custom service providers and 24 percent purchased new land, according to surveys from the Tools for Organic Transition Project.

Consider how your overall transition strategy (e.g., split-crop operation versus whole-farm transition) and specific management plans will affect your need for land, facilities, equipment, breeding livestock, storage and production inputs. Begin by drafting a list of short-term (transition) and long-term (post-certification) needs related to your facilities, equipment and inputs. Space is provided for this on Worksheet 4T.3: Crop and Live-stock Enterprises and Worksheet 4T.6: Processed Products and Services. Then, compare this list to your current inventory of available resources to identify gaps.

Once you have a good feel for short- and long-term resource gaps, begin identifying strat-egies for how you will fill land, facility, equipment and input needs. These strategies might include purchasing new or used equipment, contracting services or developing strategic partnerships to access feed, equipment or processing facilities.

Strategic partners are important to any business—they may allow you to take advantage of opportunities, inform a new idea or finance needed investments.

strategic partners

We formed an alliance with an established organic farmer who supplied equipment in

exchange for manure spreading. (We own a manure hauling/spreading business.) This

strategic alliance allowed us to experiment with organic transition without having to make substantial investments in new equipment until we were ready.

Reflect on your operations strategy. Does it make sense to fill any equipment gaps through strategic alliances? What are the advantages and disadvantages of entering into a formal or informal agreement? Would it make more sense to finance inputs, equipment and other capital assets? We discuss capital financing in the Finances strategy section.

If you remain uncertain about how best to address resource needs, see pages 138-142 in the Guide to identify additional strategy alternatives for accessing land, equipment and inputs. All of the strategies mentioned are viable options when transitioning. One possible exception concerns land rental. Renting and transitioning acreage can be risky unless you are able to sign longer-term leases where returns on investments can eventually be captured.

Use Worksheet 4T.2: Operations Strategy Summary to document land, facility, equipment, breeding livestock and input needs, and acquisition strategies. As you do so, be sure to check that inputs are approved by the NOP. The Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) maintains a comprehensive directory of materials and allowable inputs for organic production that are compatible with the NOP National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances. The Non-GMO Sourcebook is another excellent resource listing suppliers of non-GMO products and services that are particularly helpful during transition. See the Resources section for more on the OMRI Products List and the Non-GMO Sourcebook.

Inventory Management and Quality Control

Certification and, ultimately, income will be determined by how well you manage invento-ry and control quality to protect the organic integrity of your crop, livestock and processed products. Inventory management begins in the field and ends when products are loaded on a truck for delivery to buyers.

As with conventional crop and livestock products, you need to have a plan for storing products and protecting quality. Storage containers, packaging materials and pest control practices for transitional and organic products are regulated by NOP, so be sure to check the rules for allowable materials and practices.

Additionally, if marketing a specialty transitional crop where premiums are dependent on the load being “clean” (GMO-free) or if maintaining a split operation after certification, you will need to take extra steps to safeguard product quality. You will need to prevent commingling with non-organic (or GMO) products, protect organic products from coming into contact with prohibited substances, and create the traceable audit trail required by certifiers and many buyers. We discuss audit trails in the Human Resource strategy section under record keeping.

After becoming certified, if you are maintaining a split operation and expect to store crop and livestock products, it is common to dedicate separate equipment and storage for conventional, transitional and organic use. As explained by Mary-Howell Martens of Lakeview Organic Grain in New York: “If you are not using dedicated organic harvesting and handling equipment, your certifier will expect you to maintain a clean out log, showing that equipment was thoroughly cleaned and purged of conventional grain before any organic grain was introduced.”

These same rules apply when co-packing, renting processing equipment and using custom hire services for combining, cleaning, trucking and storing grain. Carolyn Lane, vice president of Nature’s Organic Grist in Minnesota, warns that custom service providers often do not take responsibility for proper clean-out when moving from conventional to organic operations. Therefore, she suggests working with a trusted service operator or hiring a certified organic farmer to provide needed services.

For more information about how to maintain product quality and prevent commingling, check out the NOP guidance sheets Commingling and Contamination Prevention in Organic Production and Handling and Can GMOs Be Used in Organic Products?. Both articles are listed in the Resources section.

Production Estimates

Next, use Worksheet 4T.7: Production Estimates, Crops and Worksheet 4T.8: Production Estimates, Livestock to record your expected yields or livestock production during the short-term transition period (the first three years) and during the long-term, post-certification period (years four and five).

Crop yield and livestock output estimates come from your own records and from published research. If this is your first time transitioning, be aware that yields and output have been shown to decline when making the switch to organic management, due primarily to an increase in weed populations. See Table 4T.1: Organic Yield Penalties for a look at yields observed in seven studies comparing conventional and organic row crops.

Figure 4T.1: Organic Yield Penalties

| Organic Yield Penalties from Selected Transition Studies, 1986 - 2008 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | Soybeans | Wheat | Hay/Alfalfa | |

| Delate and Cambardella | 8.2 | 0.4 | -- | -- |

| Porter et al. (No. 1) | 9 | 19 | -- | 8 |

| Porter et al. (No. 2) | 7 | 14.9 | -- | 0 |

| Creamer et al. | -- | 11.2 | ||

| Hanson et al. | 28.9 | 23.1 | 22.2 | |

| Dabbert and Madden | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| McBride and Greene | -- | -- | -- | |

| Average | 14.6 | 18.1 | 12.6 | |

| Source: Clark, S. and C. Alexander. February 2010. The Profitability of Transitioning to Organic Grain Crops in Indiana. Purdue Agricultural Economics Report. Purdue University. | ||||

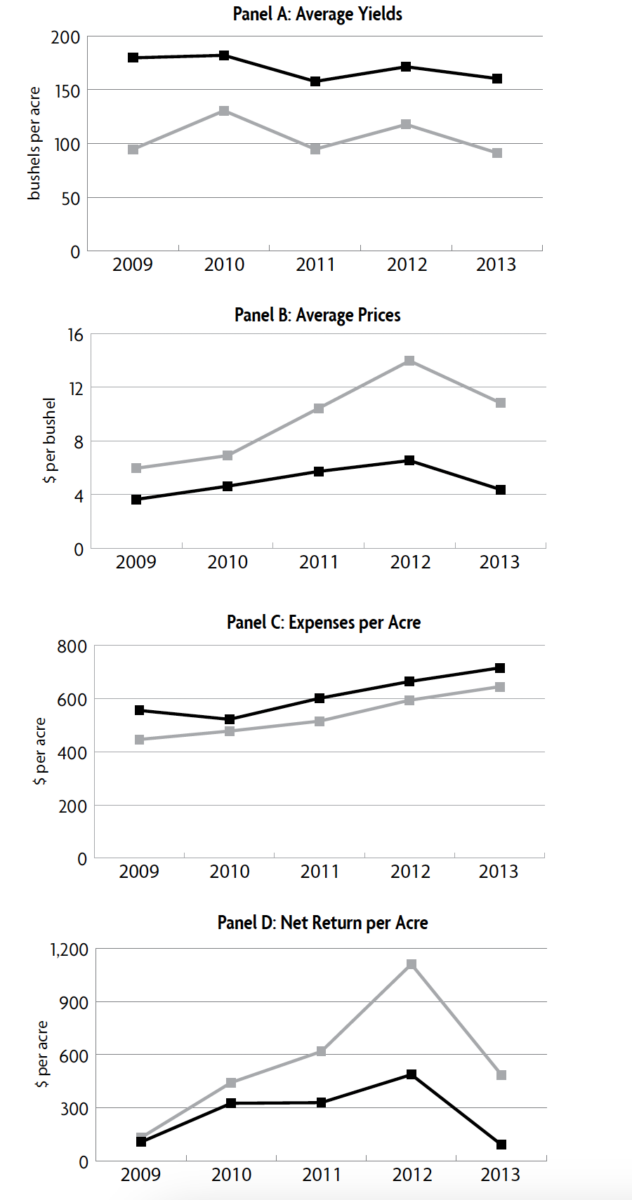

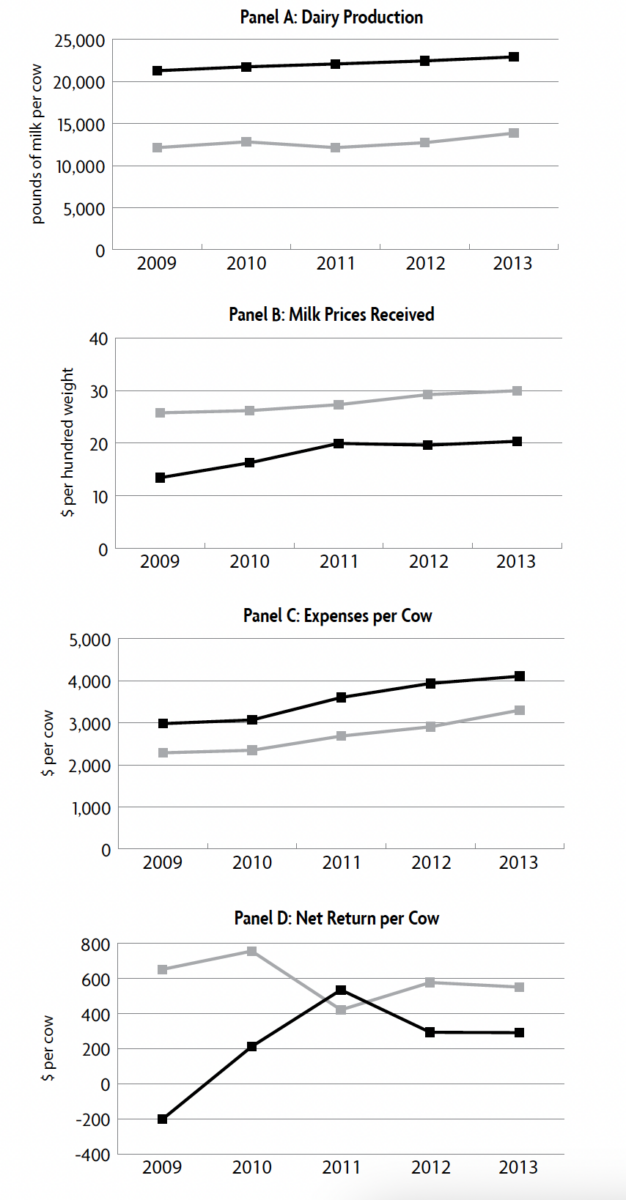

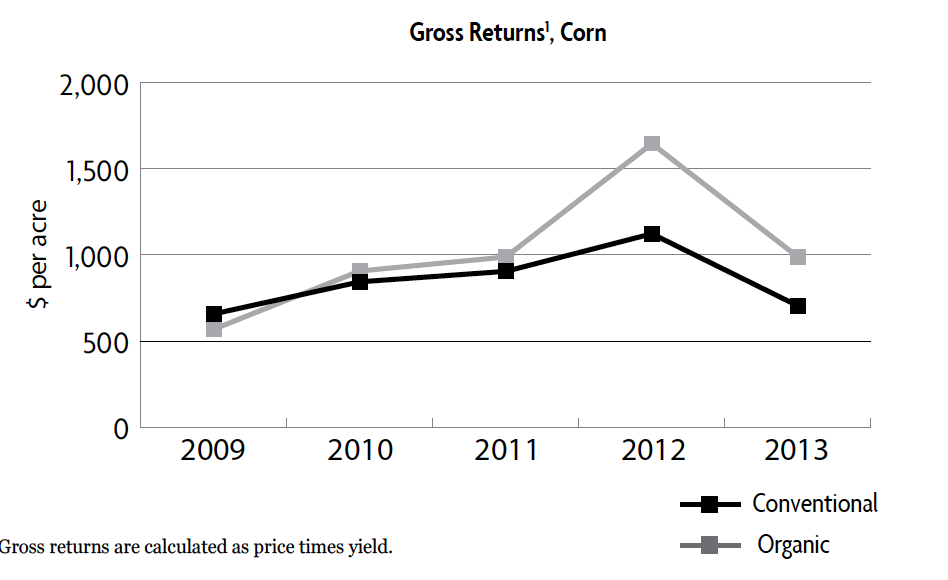

Panel A in Figure 4T.6: Conventional Versus Organic Enterprise Observations in Minnesota, Corn and Figure 4T.7 Conventional Versus Organic Enterprise Observations in Minnesota, Dairy depict more recent corn yield and dairy productivity data as reported by Minnesota farmers and their farm business management instructors.8 This data suggests more substantial yield penalties than those reported in Table 4T.1: Organic Yield Penalties. Organic corn yields, for example, averaged 53-72 percent of conventional corn yields during 2009-2013. Cow productivity compared similarly. Organic milk production per cow measured 55-60 percent of conventional milk production during 2009-2013.

Figure 4T.6: Conventional Versus Organic Enterprise Observations in Minnesota Corn

Source: FINBIN Database. Center for Farm Financial Management. www.cfffm.umn.edu. Data come from Minnesota farms enrolled in the Farm Business Management Education Program. Individual farms enrolled in the program (observations) vary each year.

However, research and data from side-by-side, long-term field trials at the Minnesota Southwest Research and Experiment Station in Lamberton, Minn., suggest that four-year organic rotations for corn and soybeans can compete with conventional, two-year rotations on a yield basis.

We have listed a few yield-related data sources in the Resources section. If you do not find what you are looking for there, we suggest talking with farmers in your area or visiting with a certifier to explore output expectations for transitional and organic crop yields and livestock performance for your county. Experienced farmers may be able to suggest reasonable yield penalty or transition effect multipliers for your own crop or animal output histories.

If processing, we suggest doing some marketing homework first. Unlike bulk commodities, which have a guaranteed market in the conventional sector if you are unable to market or-ganically, processed products—organic or conventional—require greater investments, car-ry more regulatory risk and may not have an alternative market outlet. It is a good idea to talk with buyers (described in the Marketing section of Planning Task Four) to determine sales before finalizing processing production estimates. When ready, use Worksheet 4T.9: Production Estimates, Processed Products to record the volume of product that you expect to process.

Your production estimates for processed products will likely change over time as you develop recipes, source ingredients and refine processing methods. It is not uncommon to begin by processing conventionally—for practice, so to speak—before applying for organic handling certification. See ATTRA’s Guide for Organic Processors for more ideas on how best to develop a plan for processing.

OPERATIONS - Licenses and Organic Certification

Most farmers are familiar with county, state and federal licenses and permits required for conventional management (e.g., those related to buildings, waste handling and disposal, health and safety, processing, etc.). Many of these same rules and regulations will apply when going organic. Additionally, however, there are a host of license and permit obligations that you should be aware of as a transitioning organic producer or processor. These are outlined in the NOP standards under NOP §§ 205.202-205.240.

NOP standards apply to all farmers, ranchers, processors and food business owners who use the organic claim, but certification is only required if you do one of the following:

- sell more than $5,000 of organic products annually (gross sales)

- handle more than $5,000 worth of bulk, unpackaged organic products (gross sales)

- process more than $5,000 worth of organic products (unless all products contain less than 70 percent organic ingredients)

- handle (e.g., package) and sell organic products online (but not in stores) or transport organic products

For more information about whether you should certify or need to develop an OSP, check out the USDA fact sheet Do I Need to Be Certified?, listed in the Resources section. Moreover, if you plan to process raw products, you will need to create an OSPH that describes your:

- handling

- ingredient purchases

- transportation of raw ingredients

- storage

- cleaning and sanitation

- processing flow chart and facility map

- pest management

- sales

- recordkeeping

Explore certifier options now if you have not already done so. Certification applications typically are mailed at the beginning of your third year of transition; however, it is possible to request a certification packet or meet with a certifier before beginning transition, during transition or prior to processing. Reviewing your operations strategies with a certifier or organic consultant for compliance with NOP rules will help you determine any records, licenses or permits that you may need when implementing your strategic plan.

If early certifier meetings are unavailable or are cost prohibitive, consider attending conferences, webinars and field days to learn more about NOP compliance. The Organic Trade Association’s Regional Guide chronicles events by location. Be sure to check out the series of ATTRA publications that provide documentation forms:

- Organic Field Crops Documentation Forms

- Organic Livestock Documentation Forms

- Organic Market Farm Documentation Forms

- Organic Orchard, Vineyard, and Berry Crop Documentation Forms

- Guide for Organic Processors

Use Worksheet 4T.10: Licenses and Certification to document those regulations, licenses and certification standards that will apply to your business, your strategy for meeting them, and any outstanding questions that require follow up.

OPERATIONS - Risk Management

Take time now to briefly reflect on your overall production system plans, strategies for obtaining land, equipment and inputs, and your inventory management and quality control strategy. What type of risks will you face? Which of these risks are unconnected to your transition (e.g., weather) and which risks are unique to organic transition and certification (e.g., drift of prohibited substances, change in farm program and crop insurance benefits)?

According to Tools for Managing Pest and Environmental Risks to Organic Crops in the Upper Midwest, it is commonly accepted that, “Organic agriculture is inherently riskier than conventional agriculture because of the complexity of dealing with crop management issues such as fertility, weed control and pest control. These challenges are especially evi-dent during transitioning from conventional to organic.”

Talk with certified organic farmers, Extension educators, crop insurance agents and other specialists to explore transition-related risks, particularly if you are new to farming or or-ganic management. Once you have a good feel for potential risks, use Worksheet 4T.11: Operations Risk Management to brainstorm strategies that can help you prevent or mitigate them.

The relationships that you develop with representatives of accredited certifying agencies (ACAs), Extension agencies, conservation district offices and regional organic or sustain-able farming associations will become valuable risk management strategies in themselves. For example, agency and association representatives can help you determine:

- what to do if you experience chemical drift

- how to address livestock illness

- where to go for approved input sources

- how to obtain organic cost-share

- what type of records are needed for certification

As an organic farmer, your risk-fighting strategies will look different from those of a conventional producer. You will rely on rotation, tillage alternatives and varietal or breed selection rather than pesticides, herbicides and antibiotics.

You may also consider using multi-peril crop insurance, available for transitioning and certified crops. USDA’s Risk Management Agency (RMA), responsible for establishing insurance guidelines, revised organic-friendly, multi-peril insurance policies in April 2014. The revised policies provide coverage for:

- certified organic acreage

- transitional acreage

- buffer zone acreage

Multi-peril coverage extends to basic weather-related damage (e.g., drought, hail) as well as yield losses resulting from insect damage, weeds and crop disease in the event that recognized organic farming practices fail to protect against such problems. In order to qualify for transitioning or organic coverage, you must provide the insurance agent with a certificate or written documentation indicating that an organic plan is in effect. We recommend meeting with your insurance agent and certifier prior to beginning transition so that coverage options and required documentation can be reviewed. Current transitional and organic insurance guidelines are outlined in the RMA Program Aid publication No. 1912, Organic Farming Practices.

If you plan to process, we strongly suggest that you explore food safety regulations by contacting your state department of agriculture, and adopt liability insurance. We do not discuss food safety regulations in great detail here because they are complex, evolving and apply equally to all producers, both conventional and organic. However, you should be aware that most buyers—conventional and organic—require that on-farm processing facilities maintain food safety plans, that farmers follow good handling practices (GHP) as outlined by the Food and Drug Administration and USDA, and farmers keep records related to previous land use, water tests, worker hygiene, herd health, wild animals, soil amendments and manure applications, harvest sanitation, and crisis management. See Food Safety and Liability Insurance: Emerging Issues for Farmers and Institutions as well as the On-Farm Food Safety Project website.

You might also consider developing what University of Minnesota scientist George Nelson calls “exit strategies,” or action plans for abandoning your organic transition in the event of a catastrophic crop loss, food-borne illness outbreak or the failure of other risk management strategies. We label these “recovery strategies” on Worksheet 4T.11: Operations Risk Management.

OPERATIONS - DIG DEEPER

You should feel fairly comfortable with your transition strategy for operations before mov-ing forward to explore marketing, human resources and finances. However, if you would like to do a little more exploring to determine optimal production capacity, equipment sizes and management practices, there are excellent resources available to help you do so. Another option is to review pages 143-144 in the Guide (including Worksheet 4.16: Estimating Output and Capacity) where you can explore the impact of different yield and production output scenarios. If you are new to farming or still unsure about what to include in your transitional rotation, do not worry too much about getting things just right at this point. You can always return to your operations strategy after talking with buyers, reviewing labor options and running a cash flow.

Operations - Put it in writing

Head to the Operations section in AgPlan or to your business plan word document. Begin documenting your transition strategy by listing production opportunities. Next, include a description of your overall operations management strategy. If you are considering more than one strategy, copy this worksheet and complete it for each strategy.

Describe changes in your current operation that will be necessary for your transition strategy to be successful, specifically noting land, facilities, equipment and inputs that you may need in the Resource Needs and Acquisition section. If you plan to process, include a flow chart depicting product flow and processing methods, recipes, and a list of needed investments. In other words, summarize information that will help a lender or investor understand your plan. Next, complete the Licenses and Organic Certification section of your business plan (there is space provided in AgPlan). Finally, outline potential risks and your risk management strategy using information from your risk management worksheet. Space is provided for this purpose in the AgPlan outline under Operations Risk Management.

Do not let this strategy summary get too long and do not spend much time polishing your language, as you will likely return to it and make changes after you have explored marketing, human resource and finance strategies. If using a word processing program, you might find it easiest to simply turn the information recorded on Worksheet 4T.2: Operations Strategy Summary into relevant strategy statements for your business plan.

At this point, we also encourage you to take a step back and ask yourself: Is this new operations strategy worth pursuing further? In other words, have you encountered anything unexpected when researching transition options that might change your mind? Are you better off sticking with your current management plans or does the transition strategy look promising? If your transition strategy compares favorably to your current management situation, then move right on to marketing! However, if you are not entirely convinced, you might want to review your goals and explore alternative production strategies before going too much further with your proposed transition plan.

MARKETING

Marketing, more than other aspects of your farm business, will require you to develop a two-pronged strategy—one strategy for the three-year transition period that is needed for most farmland and another strategy that kicks in once your land and animals are certified.

You have many marketing options, including sales to other farmers, forward contracting with processors, membership and sales through natural foods cooperatives, and direct sales to retailers and wholesalers. Regardless of which general strategy you adopt, you will need to make decisions about how to price, handle, label and distribute organic products in compliance with NOP regulations (§§ 205.300-205.311). We will discuss all of these topics in this section.

MARKETING - Marketing Opportunities

As you did in the Operations section, take some time now, preferably with planning team members, to identify immediate (i.e., transitional) and longer-term (i.e., organic) market-ing opportunities. You might do this by talking with commodity buyers, visiting retailers or farmers’ markets, attending a trade show or searching the Internet. You can use the space provided on Worksheet 4T.12: Marketing Strategy Summary to document general market trends that support your future vision, goals and operations strategies.

marketing opportunities

Members of Organic Valley Cooperative receive a $2 per hundredweight premium for transitional milk and approximately $28 per hundredweight for organic milk. This member price is fairly steady and guaranteed for the volume of milk we can deliver. Marketing to Organic Valley Cooperative will provide us with a stable income and access to better prices than those afforded in the conventional market.

I have been invited by the manager of the Princeton Farmers’ Market to sell naturally fermented products such as pickles, tomatoes and cabbage. This opportunity only applies to my fermented products—he is not interested in raw vegetables or herbs. The Princeton market is exclusive and currently has 23 vendors, only one of whom sells pickles that are processed using vinegar.

Market trends have been consistently positive for organic crops compared to conventional crops. The demand for organic products has grown significantly over the past 20 years, and it continues to grow at a double-digit rate. USDA reporting suggests that the conversion of land to organic production has slowed over the past few years, especially for the field crops we produce. We believe there will continue to be significant organic price premiums in the future as supply continues to lag behind demand.

Olsen Photography)

Next, outline unique marketing opportunities. These might relate to your proximity to urban areas—think direct marketing, farm dinners, homesteading classes—or to livestock producers in need of certified organic feed. Other examples of marketing opportunities are depicted in the story panels. The possibilities are endless. Keep in mind that the more unique the opportunity, the more promising it may be for your business.

MARKETING - Marketing Strategy

You are now ready to begin developing a marketing strategy for your transitional and certified organic commodities, products and services. Your marketing strategy should address:

- products and services

- buyers and sales

- pricing

- post-harvest handling, processing, packaging, labeling and distribution

- sales revenue

Products and Services

Begin by first recalling what you will have available to market during transition based on the rotation schedule and production estimates you developed on Worksheet 4T.7: Production Estimates, Crops, Worksheet 4T.8: Production Estimates, Livestock and Worksheet 4T.9: Production Estimates, Processed Products. It is always best to research market demand prior to planting, but in this publication we assume that you will develop your operations strategy and rotation schedule first. Next, identify the competitive advantages—or unique characteristics—associated with each product or service.

Your business’ overall chances of success improve with competitive advantages. We define a competitive advantage as anything that enables you to generate more sales and earn a greater profit (e.g., by differentiating your product or producing at a lower cost than competitors). Think about what type of competitive advantages your marketing and operations strategies will generate. See the story panel on competitive advantages from Vitaly Brukhman. Then, record your ideas on Worksheet 4T.12: Marketing Strategy Summary and be sure to include these ideas in your business plan—lenders, investors and business stakeholders will pay close attention to this information.

Competitive advantages

There are 13 producers of fermented products who sell at BJF-targeted farmers’ markets and retail stores. All competitor products are either produced outside the state of New Jersey, are not certified organic and/or are not naturally fermented. There is no one in the BJF target market offering organically certified, naturally fermented, locally produced pickles, sauerkraut, tomatoes and specialty beverages. Nor is any one company specifically targeting these products to ethnic communities.

Buyers and Sales

Organic markets operate quite differently from conventional markets, owing to reduced volume and price transparency. If you currently market conventional crops, for example, you may be used to selling on the spot to a local elevator post-harvest. You can still do this during transition, unless you are seeking a premium for non-GMO or transitional grains. (If interested in marketing transitional crops for a premium, contact buyers to find out which varieties they seek, their purchasing capacity and other sales criteria, such as writ-ten contract terms.)

After becoming certified, however, you will need to identify buyers and explore alternative marketing strategies, such as direct sales to other farmers or forward contracting with a broker or organic handler (e.g., processor), since traditional cash markets do not exist for certified organic commodities. You may even want to consider niche markets for low-gluten grains, specialty beans, processed products, international exports (often requiring country-specific certification) and services.

Written marketing contracts for both transitional and certified products can provide a greater sense of stability and allow for more accurate business planning.12 In fact, your lender may require a written contract as a guarantee of the going organic market price.

Nationally in 2007 (latest available data), 46 percent of all organic transactions were conducted using written contracts. Check out the Farmers’ Guide to Organic Contracts even if you are already familiar with marketing contracts for traditional commodities. You will need to be aware of how contract terms can affect organic management practices and NOP compliance. See Text Box 4T.2: Checklist for Organic Contracts for questions to review when signing an organic contract.

The bottom line is, once certified, you will have a bit more legwork to do to find a buyer and arrange the sale. You can use Worksheet 4T.12: Marketing Strategy Summary to document buyer requests, estimated purchasing capacity, market trends and your own competitive advantages. There are many opportunities in the organic marketplace! If, after talking with buyers, you decide to make adjustments to your short- or long-term rotation schedules and livestock numbers, capture those changes on Worksheet 4T.7: Production Estimates, Crops; Worksheet 4T.8: Production Estimates, Livestock; and Worksheet 4T.9: Production Estimates, Processed Products.

Pricing

Your pricing strategy, like your overall marketing strategy, will likely be different during the short-term transition (the first three years) and upon certification (the fourth and fifth years). During transition you will be able to market products conventionally, accepting bulk commodity prices. You also may have the option of pursuing modest premiums for what buyers call “identity preserved” or specialty products that include, but are not limited to, grass-fed and humanely raised for livestock, non-GMO, integrated pest management and chemical-free for grains and oilseeds, and transitional for feed grains.

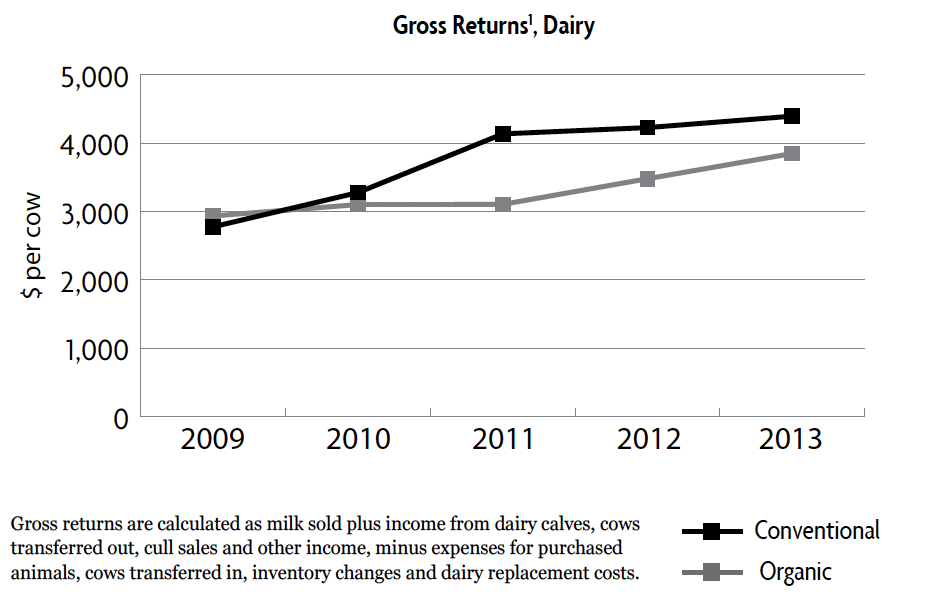

Once certified, your pricing options become more diverse and more promising. Minnesota organic corn prices, for example, averaged 149 percent to 247 percent of conventional corn prices during 2009-2013 (see Panel B, Figure 4T.6: Conventional Versus Organic Enterprise Observations in Minnesota, Corn) Similarly, Minnesota organic milk prices averaged 137 percent to 192 percent of conventional milk prices over the same five-year period (see Panel B, Figure 4T.7: Conventional Versus Organic Enterprise Observations in Minnesota, Dairy).

Contact buyers to learn more about pricing options. It is also a good idea to review avail-able price histories, since the information that you obtain from buyers only reflects current conditions, thus representing a snapshot in time. Organic grain price histories, though limited, are compiled and reported twice monthly by the USDA’s Agricultural Market News in the National Organic Price Report. This and other pricing tools, available for a variety of commodities, including some fruits and vegetables, are listed in the Resources section. (See the Rodale Institute’s Organic Price Index and the Mercaris Ceres Pricing Tool.) Once you are aware of price histories and pricing options, determine which strategy or combination of strategies make sense for you given available storage, access to trans-portation and your interest in marketing.

Finally, after talking with organic buyers and learning more about available prices, you may decide that it makes sense to revise your rotation schedule to take advantage of high-value crops during your first year of certification, or to plan for feed needs during the third year of livestock transition. If this is the case, return now to the operations strategy worksheets and make the necessary revisions before continuing.

checklist for organic contracts

Contract Interaction with NOP Regulations:

• How does the contract address certification and enforcement?

• How does the contract handle pesticide residues and prohibited substances?

• How does the contract handle GMOs?

• Does the contract set out specific isolation buffer or anti-contamination requirements?

• Does the contract address access to pasture or the outdoors for livestock or poultry?

• How are organic seed rules handled?

• Must the farmer plant a particular type of seed, such as buyer-provided seed?

• Does the contract place restrictions on the farmer’s use of buyer-provided seed, or the resulting crop?

• Does the contract give the buyer access to organic records (or certifier records)?

• Does the contract address “split operations,” or non-organic crops or animals?

• Does the contract provide support for transitioning to organic production?

Contract Stipulations Beyond Organic

• Does the contract require practices above and beyond NOP regulations?

• Must the farmer satisfy marketing claims in addition to certified organic?

• Must the farm look “pleasing?”

• Are unspecified “best management practices” required?

• Can the buyer inspect the farm?

• Does the contract incorporate separate buyer-created policies? Or laws?

• Does the contract address food safety practices?

Post-Harvest Handling, Processing, Packaging, Labeling, and Distribution

In addition to production practices, organic regulations address handling, packaging, labeling and distribution of crops and livestock products. Therefore, your business plan should include a well-thought-out strategy to address these critical issues.

If you plan to sell into conventional markets while transitioning, you will not need to create specialized handling and distribution strategies for the short term. However, if your marketing strategy hinges on the sale of specialty products during transition, such as non-GMO grain, you will need to develop handling and distribution plans similar to those required for the movement of certified organic products.

The same issues discussed in the Operations Strategy section under Inventory Management and Quality Control apply to handling and distribution of transitional and certified organic commodities and processed products. It will be your responsibility to ensure that crops, livestock products and other items for sale are not contaminated or commingled with non-organic or GMO products when marketing as transitional and certified organic (NOP § 205.272).

Finally, when labeling processed products or other items for retail, USDA permits the use of three terms for certified organic products:

- 100 percent organic

- organic (i.e., at least 95 percent of ingredients are certified organic)

- made with organic ingredients (i.e., at least 70 percent of ingredients are certified organic

Organic labeling rules are complicated and should be reviewed carefully when planning and budgeting for your marketing strategy.

Sales Revenue/Gross Income

At this point, you should have a good idea of what you will have available to sell (products and services), how much you will have to sell (yield and output), who your buyers are, how much they may purchase, and what price they are willing to pay for your products and services. Using this information, complete Worksheet 4T.13: Projected Enterprise Sales. Sales estimates in combination with cost estimates will help you determine projected income and cash flow later on in this planning task, and will allow you to evaluate the trade-off between potential yield or output reductions and potential price premiums. Figure 4T.8: Conventional Gross Returns Versus Organic Gross Returns, Corn depicts the gains for organic farms from corn sales throughout the Midwest. It shows that despite organic corn yields measuring 55-75 percent of conventional yields, price premiums of approximately $1.50-$2.50 per bushel lead to higher overall gross farm revenue.

Figure 4T.8: Conventional Gross Returns Versus Organic Gross Returns, Corn

Source: FINBIN Database. Center for Farm Financial Management. www.cfffm.umn.edu. Data come from Minnesota farms enrolled in the Farm Business Management Education Program. Individual farms enrolled in the program (observations) vary each year.

Figure 4T.9: Conventional Gross Returns Versus Organic Gross Returns, Dairy

Source: FINBIN Database. Center for Farm Financial Management. www.cfffm.umn.edu. Data come from Minnesota farms enrolled in the Farm Business Management Education Program. Individual farms enrolled in the program (observations) vary each year.

MARKETING - Licenses And Certification

Whether you raise commodities or plan to process, you will have to do a fair amount of research into required marketing-related licenses and certification.

Organic commodity buyers, for example, often require sellers to provide a “clean truck affidavit” proving that the vehicle used to transport grain and other commodities was properly cleaned before hauling specialty or organic loads. In addition to the clean truck affidavit (copies are available from certifiers and buyers), most buyers will expect you to provide the following with each delivered load or immediately after arrival.

- Copy of current organic certificate, if delivering an organic crop

- Product listing, or an addendum to certificate showing crop(s) or product(s) produced

- Bill of lading listing farmer, buyer, product and lot number. This is your proof of shipment. Your certifier or buyer can provide a blank bill of lading if you need one.

- Transaction certificate (TC), if delivering a certified organic product. This is issued by your certifier to verify the sale for auditing. The TC contains a serial number and “documents the details of a transfer of ownership of a certified organic product, such as the date, the parties involved in the trade, the commodity traded, the quantity, the lot number of the product, and the organic certificate number under which the operation was certified.”15 A TC is not required by all buyers.

If you plan to process products and market them as certified organic you will need to develop an OSPH and apply for additional certification through an approved certifier. Handling regulations are similar in intent to production regulations. They stipulate that processing, packaging and distribution procedures present no risk of contamination from non-organic products, synthetic fungicides, preservatives or fumigants.

Finally, labeling requirements are complicated and are treated in NOP regulations §§ 205.300-205.311. We recommend that you very carefully review organic labeling and handling regulations with a certifier. Certifiers are required to review and approve any packaging and labels before they can be sold at the retail level. It will be important to plan for these as part of your marketing strategy. See the Resources section for USDA handling and labeling guidelines and fact sheets as well as the Organic Handler Certification Support Package from the California Certified Organic Farmers organization and the Guide for Organic Processors from ATTRA.

Marketing Risk Management

If you are an experienced conventional producer, you likely are familiar with market vola-tility and the price risk that comes with it. There are many strategies available to minimize price risk, including the use of contracts to lock in returns and storage to ride out market volatility. As an organic producer you can use most of these same tools. You have the option of contracting based on price, field or yield. In addition, as a milk or specialty grain producer, you may have the option of joining a cooperative that offers purchasing and pricing guarantees. Likewise, you can store grain in anticipation of price movement.

You also may face some unfamiliar risks having to do with product quality, handling, packaging, processing and labeling. For more information, review the NOP sales-related regulations § 205.300-205.311. Finally, if you are planning to contract grain or other products, be sure to review the organic contract checklist in Text Box 4T.2: Checklist for Organic Contracts. Contracts do offer an opportunity to manage risk by locking in or securing a price. However, contracts also bring with them delivery obligations and NOP compliance risks, also outlined in Text Box 4T.2. See Farmers’ Guide to Organic Contracts.

Clearly, there is a lot to consider. Ask questions, visit with other farmers, attend trade shows where buyers are present and visit with certifiers. Moreover, talk things over with your planning team. These are great ways to refine your marketing strategy. Then use Worksheet 4T.12: Marketing Strategy Summary to sketch out a plan for each major commodity or enterprise that you expect to sell during transition and during your first two years of certification. Do not overlook the Business Plan Input section at the end of the worksheet. Summarizing your marketing plans for each product or service here will make your work in AgPlan much easier when you are ready to begin writing.

Marketing - Dig Deeper

Planning to direct market? If so, you will need to do a lot more work to identify your cus-tomers and the products that they may be interested in buying. Pages 106-131 in the Guide address direct-market issues such as customer preferences, competition, distribution, packaging, pricing and promotion. It will be critical to explore questions related to these topics if you intend to sell directly to retailers or customers.

Marketing - Put it in Writing

Use AgPlan or a word processing program to record your marketing strategies. Use in-formation from each of the marketing worksheets in Planning Task Four to complete the following sections of your marketing plan:

- Marketing Opportunities

- Marketing Strategy

- Licenses and Organic Certification

- Marketing Risk Management

Alternatively, you can choose to draft your own outline or simply summarize key ideas that describe your overall marketing strategy in the appropriate marketing sections of AgPlan—there are lots of options! Take a look at the completed transition plans in the Appendix for more ideas on how to prepare the marketing strategy section on your business plan.

Eventually, we suggest including copies of marketing contracts or other written sales agreements as appendices in your business plan, because most lenders will expect to see them. For this purpose, AgPlan allows you to easily import Word, Excel and FINBIN documents. Once complete, carefully review your written marketing strategy and supporting documents. Is it compatible with the operations strategy that you developed earlier? For example, are there viable markets for the crops in your rotation? Or are there opportunities to market alternative crops? If so, does your rotation and planting schedule need tweaking? Recall that strategy development is an iterative process. It is not unusual to adjust as you go.

HUMAN RESOURCES

Organic farming is management intensive. Field trials, national and local surveys, as well as anecdotal feedback from farmers suggest that organic farming requires more field work, more recordkeeping and more time on the phone (e.g., tracking down input suppliers and buyers). In fact, 32 percent of all Tools for Transition Project survey respondents who converted from conventional production reported hiring additional labor when transitioning to organic.16 For these reasons, it is worth taking this next assignment seriously.

HUMAN RESOURCES- Human Resource Opportunities

Do you have the opportunity to shadow another farmer or processor? Does a family member possess unique skills that can be applied to your plans to market a processed product? Do you know someone who is looking for an organic farm internship? Or do you have a child who is graduating from college and wants to farm? Or, perhaps, like Bryan and Theresa Kerkaert, you have an excess capacity of labor due to external changes in rental contracts. See the human resources story panels for examples.

HUman Resource Opportunities

Loss of a significant portion of our rented land represents a significant challenge and opportunity for our farm business. We currently have excess labor and management capacity. Acquisition of more land through a long-term lease with an option to buy will give us an opportunity to better use our labor and management resources.

Human resource opportunities may make all the difference in your farm business’ successful transition to organic production and marketing. Take time now to document the unique skills offered by family members and to brainstorm other human resource opportunities that will lend your business a competitive advantage. You can record your ideas on Worksheet 4T.15: Human Resource Strategy Summary.

HUMAN RESOURCES- Management, Planning and Workforce

If you are an experienced farmer or business owner, you already have a wealth of information and knowledge under your belt. It is important to capture this information in your business plan. Use Worksheet 4T.16: Acquired Knowledge to document your organic management knowledge or experience. If you are not sure what to include, return to Worksheet 2T.10: Are You Ready to Manage Organically? for a few ideas. If you are new to farming, document business expertise and other experiences that exemplify management skills. Additionally, experienced or not, you might want to use Worksheet 4T.16: Acquired Knowledge to describe needed skills and how you plan to acquire them. For example, you might list organic workshops, webinars and field days that you anticipate attending. Check out the story panel on acquired knowledge from beginning farmer Vitaly Brukhman.

ACquired knowledge

BJF will be managed by owner Vitaly Brukhman. While new to farming, Brukhman has experience as an entrepreneur and has operated a successful IT consulting business. In 2013-2014, Brukhman began cultivating his agricultural production skills, acquiring hands-on experience growing radishes and mustard greens on a half-acre while completing a beginning farmer education program with NOFA-NJ. During the spring/summer of 2014, Brukhman participated in four courses as part of the Organic Processing Institute’s School for Organic Processing Entrepreneurs to gain a better understanding of organic processing and handling requirements. During that same time, he conducted food product research and began small-batch production for taste testing and marketing. In the fall of 2014, Brukhman continued skill-building coursework: farming-related classes and on-farm consultation with NOFA-NJ, a class on food and drink entrepreneurship with the Samuel Adams Brew the American Dream series, and microbiome and nutrition studies through a variety of online sources.

Additionally, Brukhman plans to enroll in the food safety manager program offered electronically by ServSafe, a nationally recognized training program. This course satisfies the Middlesex County food safety training requirements needed to obtain a New Jersey food service sanitation certificate. Training is valid for five years from date of completion.

Next, take another look at your planning team and board of directors. Collectively, do they have the expertise to guide you through transition, certification and any other significant changes that you plan to make? If not, consider adding new members who can provide honest and informed feedback about proposed short-term transition strategies and long-term organic management strategies. These new members might include certifiers, handlers, organic consultants, financial planners and experienced farmers. They will become a very important part of your management team. See the planning team story panels.

Planning Team

In addition to Bryan and Theresa, the management team for Kerkaert Organic Farm includes:

- Paul L., Farm Business Management advisor

- Dale P., bank loan officer

- Rod D., Farm Service Agency loan officer

- Central Crop Consultants

- Minnesota Crop Improvement Association, organic certifier

- Jon O., organic farmer, friend, mentor

We have all been working together for several years and believe we will continue to be a strong team as we grow our business.

Human Resources - Human Resource Strategy

Tasks and Recordkeeping

Use Worksheet 4T.17: Management and Workforce Responsibilities to identify farm business tasks associated with production, marketing and overall management. Most of the new responsibilities or tasks will be fairly easy to identify.

Recordkeeping, however, is one of those management tasks that can be overlooked or underestimated when exploring organic certification for the first time. Of all the new tasks that you will perform as an organic farmer, recordkeeping is, perhaps, the most time consuming.

Many conventional farmers use production, marketing and financial records to help them manage more efficiently. Records are equally helpful for organic management but also are required for NOP certification. NOP regulations state that farmers must keep records that “are adapted to the operation … disclose all activities and transactions … [are] maintained for not less than five years … and [are] sufficient to demonstrate compliance.” (NOP § 205.103) As already discussed in the operations and marketing sections, you will require records to document:

- production

- harvesting

- post-harvest handling

- storage and transport

- processing

- packaging and labeling

- sales

These records help form the production audit trail, verifying that farm products have been produced, harvested and handled in accordance with NOP rules. As a farmer, you are responsible for maintaining an audit trail as long as you own the product. Unique lot numbers, developed by you, are used to trace products through the audit trail. A lot number generally indicates the type of crop, field number or storage unit, and year of production.18 See the Minnesota Guide to Organic Certification for an excellent discussion on how to establish an audit trail and create lot numbers for your farm. The publication also includes record-keeping templates useful for establishing an audit trail. The comprehensive ATTRA publication Documenting Forms for Organic Crop and Livestock Producers walks readers through records needed for certification and provides sample templates for record-keeping use. Both publications are listed in the Resources section. Also consider visiting with a certifier, attending workshops and talking with certified farmers to learn more about record-keeping options.

You can use Worksheet 4T.18: Recordkeeping Strategy to outline your approach to recordkeeping. A short discussion of your recordkeeping strategy within the business plan will provide your lender or other business partners with confidence that the transition will be a success.

It is never too early to start! Keeping good records before implementing major changes will establish a baseline against which you can measure progress as you transition and implement new business strategies.

examples of records needed for organic certification

- Previous land use record

- Soil tests

- Production activity log

- Planting and rotation records

- Input material records

- Marketing contracts

- Harvest records

- Storage/inventory logs

- Sales transactions

- Prevention of commingling and contamination records

- Clean transport affidavit

- Equipment cleaning log

- Complaint log

Workforce and Professional Services

Once you have identified new tasks to be performed, brainstorm short- and long-term strategies for accomplishing this work. Think about who will manage the farm business as well as how and where you will source labor to accomplish each new task. Remember, labor may be seasonal or year-round, part-time or full-time, family or non-family, and may come from custom service providers or other farmers who are interested in partnering to share equipment and tasks.

Use Worksheet 4T.17: Management and Workforce Responsibilities to describe your plans for filling specific management and labor tasks throughout the transition and during the first few years of certification.

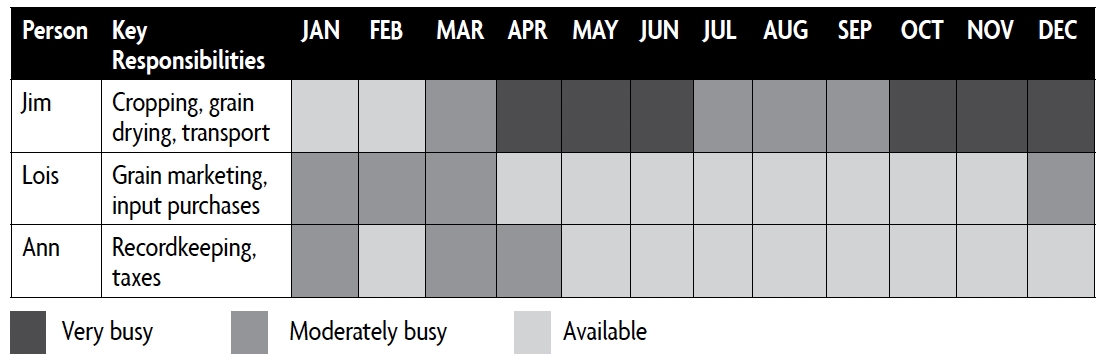

Next, think about how these tasks will change for each member of your farm business during the transition period and after certification. You can use this worksheet to document each per-son’s key responsibilities during transition and after certification—pairing their responsibilities with their known skills. It will be important to note when they will be most busy and least busy, which will help you identify any bottlenecks that may occur under your new transition plan.

Finally, return to Worksheet 4T.15: Human Resource Strategy Summary to summarize your human resource strategy. Be sure to address plans for complying with NOP record-keeping requirements.

You can map out your team’s responsibilities in any number of ways, an exercise that will help you anticipate potential labor bottlenecks. For example a simple list will do, as on Worksheet 4T.17, or you can use a grid, as you did on Worksheet 2T.9: Current Human Resources.

HUMAN RESOURCES - Human Resource Management

Human resources represent one of the greatest and most unpredictable risks that your farm business will face. It is nearly impossible to know when someone will be injured, whether circumstances will force a change in off-farm employment or if unforeseen health issues will arise. So, while you cannot plan the business around unknowns, it is good to ask “What if?” as part of your strategy development. We suggest exploring common human resource risks associated with acquiring seasonal labor, securing buy-in from all family members on a new idea or filling knowledge gaps. Use Worksheet 4T.19: Human Resource Risk Management to identify labor and management-related risks and to explore strategies for addressing and minimizing them.

Human Resources - Dig Deeper

Does your transition strategy rely on hired labor? If so, you will want to dig a little deeper to explore hiring and compensation as well as good communication practices. Be sure to include your hiring and compensation strategy under Human Resource Strategy if using AgPlan or the human resources section of your business plan.

Human resources - Put it IN Writing

Put your human resource strategies down on paper using a word processing program or the following sections in AgPlan: Human Resource Opportunities, Planning and Management Team, Licenses and Safety Regulations and Human Resource Strategy. If you completed Worksheet 4T.16: Human Resource Strategy Summary and Worksheet 4T.18: Recordkeeping Strategy this exercise should be relatively simple. Take a look at the completed transition plans in the Appendix for more ideas on preparing your human resources strategy section on the business plan.

FINANCES

A sound financial strategy is a critical element of any business plan. This is where the rubber hits the road, so to speak—when you identify whether concepts and ideas are financially feasible. If your strategies do not generate earnings or meet other basic financial goals, then some revision will be in order.

When developing a financial strategy, begin by reviewing your current financial position: Look at your current balance sheet, income statement and annual cash flow. You prepared some of these in Planning Task Two: History and Current Situation. Next, we suggest that you take another look at your recently developed operational, marketing and human resource strategies to study how proposed changes will affect your farm’s current financial picture. For example, how will changes in expected crop and livestock input expenses, out-put and prices affect your current cash flow and year-end profitability? How will anticipated equipment purchases and financing needs affect net worth?

Your transition will have a greater chance of success if you go into it knowing the numbers and having identified strategic alternatives to address any cash flow issues and capital needs. Many farmers who participated in the Tools for Transition Project told us that the third year of transition was the most difficult financially, but that knowing what was on the other side—namely, the boost in farm income from organic premiums—made it possible to get through challenging times.

FINANCES - Financial Opportunities

Take some time to identify and explore financial opportunities (e.g., low interest rates, potential investors). Some growers are fortunate enough to have “angel investors,” or financial partners who provide capital on loan with flexible terms. These investors might be people you know, formal business partners, family members, other business owners or members of the community. See the financial opportunities story panel for an example from Vitaly Brukhman’s business plan. Then, use Worksheet 4T.21: Financial Strategy Summary to identify financial opportunities available to you and your farm business.

financial Opportunities

BJF has been approached by a private investor who believes in the BJF mission and who is interested in loaning our farm business enough money to cover all start-up expenses. We consider this an extraordinary financial opportunity!

FINANCES- Final Projections

A financial strategy, just like your operations, marketing and human resource strategies, should be forward looking; it should be based on projections of enterprise sales, net farm income and asset growth over the next five years or more. However, because you are likely managing a family farm, the business will also need to cover some, if not all, family living expenses.

Begin by reviewing how much money will be needed to pay for annual family living expenses using Worksheet 4T.20: Projected Family Living Expenses. This will set the bar for farm income requirements during transition and upon certification. You will need to generate the equivalent of family living expenses plus other projected financial needs (e.g., college tuition, retirement, loan repayment) from farm income, plus any off-farm income that you or your partner expects to earn. If you do not anticipate living expenses changing much from their current level, you can skip this worksheet and use the one you prepared in Planning Task Two (Worksheet 2T.12: Family Living Expenses) to establish a baseline.

After recording family living expenses, turn to farm business expenses. Use Worksheet 4T.22: Projected Farm Expenses to outline direct and overhead expenses for the whole farm. The worksheet provides typical farm expenses as well as those unique to organic production (e.g., certification fees).

If you are unfamiliar with organic input costs, you will need to do some homework to develop expense estimates for transition and certification years. Note, however, that on-farm expenses vary considerably by region, farm size, supplier, market conditions and management practice. You will benefit from talking locally with other farmers, lenders and input suppliers to verify costs and to develop appropriate expense estimates for your farm business and transition strategy.

There is space on Worksheet 4T.22: Projected Farm Expenses for one whole-farm transition strategy that you are considering. If, at this point in the planning process, you are still considering more than one whole-farm strategy, make copies of this worksheet and complete for each strategy under consideration.

With enterprise sales and farm expense projections in hand, you are ready to develop a five-year projected income statement using Worksheet 4T.23: Projected Income Statement. This is where everything comes together—productivity, prices and input expenses. You may be surprised at some of the results. Returning to the Midwest corn and dairy data discussed earlier in this planning task, you will note that even though the organic farms reported reduced yields or production, net farm income was significantly higher than that for the conventional farms. This was due to organic price premiums and reduced input expenses.

Once you have estimated and recorded your farm’s projected farm income over the five-year planning period (three years of transition and two years of certification), use Worksheet 4T.24: Projected Cash Flow to develop a five-year cash flow statement. As the authors of AgPlan note, “a projected cash flow will help you determine if your plan can meet expenses, make debt payments and make it through the transition period.” It is not uncommon to encounter cash shortfalls during transition, for example when expe-riencing reduced yields or production losses prior to receiving organic price premiums. Although it may not happen to you, it is very important to plan for the possibility that it will. The Twelve Steps to Cash Flow Budgeting web page by William Edwards is a good resource to help with cash flow planning (see the Resources section). It includes cash flow tips and an Excel spreadsheet you can use to calculate a detailed cash flow for corn, soybeans, livestock and other enterprises.

Finally, use Worksheet 4T.25: Projected Balance Sheet to estimate net worth- related gains or losses during the transition period and in year five (i.e., two years after certification). The balance sheet is a good indicator of whether or not your farm business is building assets over time; it depicts “everything you own, everything you owe and what would be left if the farm had to be sold.”

FINANCES- Financial Strategy

You are ready now to develop a financial strategy—one that builds on information captured in your financial projections. Financial strategies outline how your whole-farm plan will be financially successful and includes your ideas for business organization, asset acquisition and capital requests.

Business Organization

It is unlikely that your farm organization status will change as a result of transition unless your strategy involves forming new partnerships. Regardless, take a moment now to document as part of your business plan how the farm is or will be legally organized.

Ownership options include a simple sole proprietorship, a limited liability company (LLC) or a corporation. The business structure that you choose ultimately will affect your liability and tax responsibilities. Most farms are organized as a sole proprietorship or LLC. Each form of organization has its advantages and disadvantages. We suggest that you explore these by consulting your accountant or attorney as well as other resources, such as those available from your state’s secretary of state office and from groups such as Farm Commons (see the Resources section). If you decide on an LLC or corporation, you may need to create an operating agreement, depending on your state laws. This can be a simple document or statement in your business plan describing the farm business owners, profit distribution and contributions made by each owner to the business.

As a new farmer, you may also want to apply for a farm tax identification number, which will allow you to qualify for deferred estate taxes, conservation easements and, most importantly, tax exemptions on equipment purchases. Qualification criteria vary by state, but generally anyone who sells products off-farm (i.e., does not produce exclusively for home consumption) is eligible for a state farm tax identification number. For more information, contact your state department of agriculture or the Internal Revenue Service.

Asset acquisition and capital requests

The key element of this plan is to identify and secure long-term access to a parcel of land that can be a stable basis for continuation of our farming operation. … When we have identified a specific parcel of land for the new farm we will explore the possibility of negotiating a lower land rent for the transition years of 2016 and 2017. In addition, this plan is addressed to our lender, Farm Credit Services, as a request for a line of credit that will be adequate to ensure access to capital during the difficult 2015 and 2016 transition crop years.

Use Worksheet 4T.21: Financial Strategy Summary to document whether you have qualified for a farm tax identification number and to show how you plan to legally organize the business.

Asset Acquisition and Capital Requests

After compiling expense, income and cash flow projections, you may find that, in the long run, your financial outlook is bright. In order to get there, however, you may need to finance operating expenses, purchase equipment or even purchase additional land during the transition years.