For 14 years, New Hampton, Iowa, farmer Tom Frantzen reared hogs from farrow to finish, alternating the 1,200 hogs he raised annually from closed buildings each winter to pastures each summer. The buildings, where Frantzen raised the sows in pens with slatted floors, were an unpleasant winter home. In the cold months, the hogs did not gain weight very efficiently and behaved aggressively.

Pig waste fell through the slats into a pit. Frantzen pumped and disposed of manure on his crop fields, where he grew corn, soybeans and hay. "Our manure management was haphazard," he recalls. "I was both over-applying and under-utilizing those nutrients."

Frantzen had to race to the finish line every season. And while he always got everything done, reaching that point was difficult and stressful. In 1992, he decided to create a more environmentally sound system that would be both profitable and allow him to spend more time outside. The linchpin: a combination of pasture and housing that brought his livestock and crops into sync.

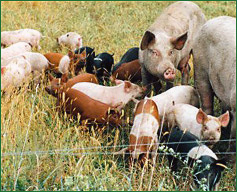

Today, permanent pastures, rotating strip pastures and cropland offer him a plethora of options for feeding pigs, including having them "hog down" - or self-harvest - crops. As they move across the fields, the pigs spread their own manure. Deep-straw bedding in huts or sheds provides warmth and exercise for the animals and produces a pack of solid waste that is far easier to handle and spread on crop fields than the slurry from Frantzen's former liquid manure system.

The new life cycle worked. After receiving a producer grant from USDA's Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) program to document the economics of farrowing hogs on pasture, Frantzen found he could halve his feed costs compared to his former indoor/outdoor system. The SARE grant "showed we can produce a 30-pound feeder pig for half the price that you can indoors," he said.

Over three years, Frantzen's costs to raise a pastured feeder pig ranged from $10 to $13.50, taking into account all supplemental feed, land expenses and labor.

"On a farm that produces grain and finishes hogs, we want the grain to go into the animal during the finishing stage and the manure to go back to the crop fields," said Frantzen, who also raises 75 Angus brood cows. "From the hoops, I can put composted manure on the correct field at the correct time. The odors aren't bad, there's no pumping involved and it puts the animals in an environment they like."

Today, Frantzen is as busy as ever, but he is a lot happier. "Working conditions for me weren't nearly as good as working outdoors," he said. "The health of the animals wasn't good, either. You could almost see the stress on the sows in the farrowing crates. Now, they seem to enjoy life. And so do I."

Farmers like Frantzen who successfully produce pork on a small scale have preserved their independence in the face of the consolidating hog industry. In the late 1980s, hogs began disappearing from small family farms. Now, most pigs are produced by corporations, with 35 percent of hogs sent to market produced by just 20 firms selling more than 500,000 per year. Usually, one company owns the pigs and retains farmers to raise the animals - often on the farmer's property, using his buildings and manure lagoons.

Those changes have narrowed choices for farmers, steering most toward a new option - working under a contract using the corporation's methods of production. Corporate contracts offer pork producers more certainty about earning modest profits than raising pigs independently but also require farmers to shoulder considerable debt to construct confinement buildings and assume environmental liability for manure.

The corporations own the processing plants and distribution system, too, effectively locking small, independent producers out of the wholesale pork market. "It is hard for small producers to put together a semiload of market hogs or find a buyer who will even accept hogs without a contract," said Martin Kleinschmidt, an analyst with the Center for Rural Affairs. "If you want to sell commodity hogs, you have to be big. If you want to stay small, you have to look for niche markets."

This bulletin showcases examples of another way to raise pork profitably.While many of the farmers profiled here have assumed bigger workloads - particularly in designing hog systems that work on their farms and identifying unique marketing channels - all appreciate the greater flexibility and a better quality of life inherent in systems with alternative housing or a strong pasture component.

Use this bulletin to gain ideas about alternative swine systems, then consult the list of resources for more detailed information.