by Lisa Bauer

Minnesota farmer Nolan Jungclaus' great-grandfather homesteaded the family farm in 1896. But a century later, the crop farm was no longer generating enough revenue to support the three families involved with the operation.

Looking for an income- generating practice that would allow him to quit his off-farm job and help support three families, Nolan Jungclaus decided to test a Swedish-style system on his Minnesota farm. With Iowa State University researchers and farmers, he traveled to Sweden to look at the systems firsthand.

Jungclaus found that Swedish farmers fit the system to the animal rather than the animal to the system. In so doing, hog producers must have excellent animal husbandry skills, an appreciation of pig behavior, attention to detail and a desire to work with pigs in a more natural environment.

In 1994, Jungclaus received a SARE producer grant to adapt an existing 36-by-60 foot machinery pole shed to accommodate four phases of Swedish-style swine production: breeding/gestation, farrowing, nursery and finishing. Lack of experience with livestock led the Jungclauses to decide on a low-cost structure that would be adaptable enough to allow the family to use their investment in other ways, if necessary.

'We wanted to maintain flexibility in our operations so that if we were poor managers or if there were drastic changes within the hog industry, we could still salvage our investment,' Jungclaus recalls. 'Our goal was to diversify the current farm operation by establishing a farrow-to-finish swine facility with attached pasture.'

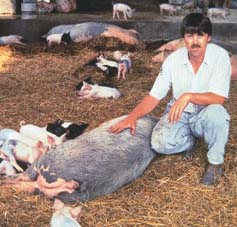

They purchased 15 bred sows the first year. Having all of the sows farrow within five days is ideal for the system, although the Jungclaus' sows farrowed over a 10-day period. They started their sows in temporary nesting boxes measuring about 8 feet by 8 feet that they removed after a week to allow sows and piglets to roam inside the building.

They provided ventilation from intake and exhaust fans, plenty of space (the equivalent of about 80 square feet per sow and litter), and quiet surroundings where the pigs can exhibit natural desires to nest and live in family units.

In the first year, the operation showed a small net loss, but that took into account the $10,682 in initial capital purchases and livestock supplies the first year.

'Overall we had a net worth increase of $7,213,' said Jungclaus. 'Although there will be some capital improvements made to the system, I anticipate a profitable system based on a capital investment loan payment of only $2,400.'

Six years later, Jungclaus has found that he can turn a profit using the Swedish-style system. In fact, he improved farm efficiency from 65 percent to 70 percent, meaning he now spends 65 cents per dollar earned, thanks to the more diverse farm operation.

While Jungclaus now raises about 400 head a year and markets the hogs through a buying station, his involvement with the new Prairie Farmers Cooperative means he will soon be able to sell his pork as a 'natural' meat free of antibiotics. Jungclaus serves on the co-op board, which is overseeing construction of a new hog processing facility scheduled to come on line before the end of 2001. Already, two grocery store chains in the area have expressed interest in the co-op's product.

The Swedish-style system produces a happy, healthy pig free of antibiotics and offers the Jungclauses a clean, healthy working environment. Jungclaus now farms alongside his children, who are often found playing with piglets.

'We felt diversifying our farm was the first step, but there were other family and community oriented goals we considered,' he said. 'We wanted a livestock enterprise that would allow us to work together as a family unit and that would increase our family time and give us the opportunity to teach our children responsibility. We also wanted a community-friendly facility because we are one mile down the road from town.'