There are many different options for delivering online outreach, from social media and streaming video to web meetings, webinars and multi-session online courses. Selecting the right platform and approach begins with thinking through your outreach and educational objectives.

Consider the following questions before planning an event:

Goals

- What do you want the group to learn and/or accomplish?

- What is the overall change you’re working toward?

Audience

- What cultural, regional, racial or ethnic considerations need to be considered?

- What motivates participants to attend? What takeaways do they want?

- What do they already know/believe?

- What are their barriers to participation?

Logistics

- What is the size of the group?

- How many sessions will there be and what is the overall duration of engagement with your program?

- Does a virtual model enable you to include speakers who would normally be hard to get to an in-person event?

Equity

- Does a virtual approach bias content towards certain audiences over others? Are there ways to overcome this?

- Is there a way that BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) women or communities might not feel welcome in the virtual space we are creating? Consider the same question for women who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or queer (LGBTQ).

Inclusion

- Who might be left out by moving to a virtual platform?

- Whom might a virtual event provide additional opportunity for?

- Will there be ways to bring folks into the planned event/experience if they don’t have internet connectivity?

The answers to these questions will help you decide both on the technology and on the facilitation and instructional methods that are well suited to meet your goals.

Challenges With the Online Approach

When approaching online program design, there may be a tendency to assume that the internet is a democratic public space where race or class or geography don’t exist.

Unfortunately, the internet isn’t a racial utopia, and many “utopian hopes for the internet as a space that transcends racism” are largely a byproduct of early web users being primarily white, as there continues to be segregated uses of online spaces (and access issues as laid out in the limitations section above) by different racial groups based on where people feel safe or seen (Kanjere 2019). Much as we seek to create safe online spaces for women in our outreach, we have to acknowledge that BIPOC women may not feel safe in those same spaces unless organizers take a critical approach to thinking about how whiteness informs their organizational approach. Indeed, Nakamura and Chow-White (2012) argue that no matter “how digital we become, the continuing problem of social inequality along racial lines persists.”

Further, those who lack access to broadband internet, including many rural farmers and ranchers, are also at a disadvantage in accessing online content, and therefore we acknowledge that there is “a digital divide in racially determined access to online spaces,” (Nakamura 2012) and that, more generally, broadband access is a space of growing inequality along intersecting lines of gender, race/ethnicity, rurality, income, education and age (Tolbert 2006). In rural areas, according to the FCC, about 65% of residents have access to high-speed fixed internet service, compared to about 97% of Americans living in urban areas (FCC 2020). And on Tribal lands, fewer than 60% of residents have access (FCC 2020). Nationwide, racial minorities are less likely to have broadband service at home. For example, 67% of Black and 61% of Latino households had broadband, compared to 79% of white households, according to the Pew Research Center.

We also had to learn the ins and outs of the Zoom platform, ensure security via registration, build curriculum appropriate to the online setting, and test out how to play videos within Zoom meetings to replace the hands-on components of in-person events.

Caitlin Joseph, American Farmland Trust

While online offerings are an important way to continue farmer education and networking when in-person meetings are impossible, and while they may provide access for some people who could not attend in-person gatherings, they may remain beyond the reach of underserved audiences for whom information, skill development and networking could have critical impact. While our work here does not contend with these issues explicitly, we feel it’s important that they guide the way we think about putting on online events, particularly because mainstream agricultural and ranching spaces (and resources) are typically dominated by white people and are infused by a culture of whiteness given the legacy of agricultural land ownership (Horst 2019).

We encourage organizers to take an equity lens to their programming, including their online work. To this end, you may need to think of additional issues when organizing your events, including whether you want to or can provide interpretation resources for participants whose language is not the dominant language used in the online event. This also might require you to seek out new partners who are embedded in communities you’re trying to reach to be partners in the co-production of your events so that they truly meet the needs of the target audience. We recommend engaging with this work with great humility and compassion, as well as with earnest commitment.

Learning Objectives

We encourage you to take the time to develop learning objectives that identify specific and measurable ways to understand what learners will be able to do as a result of participating in your program. Many times, this is not an easy task, but it pays off in several important ways, especially in a virtual environment. It helps you focus the design of your program both in terms of format and content to achieve those core learning goals. Well-crafted learning goals include both the objective and an indicator that the goal has been met. Here are some example learning goals and indicators.

| Learning Goal | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Participants will adopt approaches that other farm women have found successful for having family conversations about farm succession planning. | End-of-session indicator Participants identify at least one approach they heard about in the session that they plan to try in the next six months. Follow-up indicator (at six months) Participants report using at least one approach they heard about in the Learning Circle. |

| The Learning Circle will foster supportive connections between participants. | Post-event indicator Participants list two people from the Learning Circle whom they plan to continue to communicate with over the next 12 months. Follow-up indicator (at 12 months) Participants report ongoing contact via email, phone, social media or face-to-face visits with at least one person from the Learning Circle. Follow-up indicator (at 12 months) Participants describe these interactions in positive language. |

Tools and Technology

This section provides information on what technological tools you might utilize to meet the goals and objectives you laid out during the planning phase. Also, see the discussion on using technology to optimize virtual sessions in “Toolkit Resources.”

The technological platforms for hosting virtual gatherings are constantly evolving and improving, so these recommendations are by no means comprehensive. Rather, we provide a few tips on which platforms have worked well for women in agriculture programs in 2020. Many tools mentioned here can also be combined and integrated across platforms to enhance the user experience.

| When you need to ... | ... look for a ... | ... such as: | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capture input before and between meetings | form builder | ||

| Gather and interact in real time (e.g., Learning Circles, collaborative meetings) | meeting platform | ||

| Deliver in-depth information but not necessarily get in-depth feedback from the audience (e.g., a webinar or lecture) | webinar platform | ||

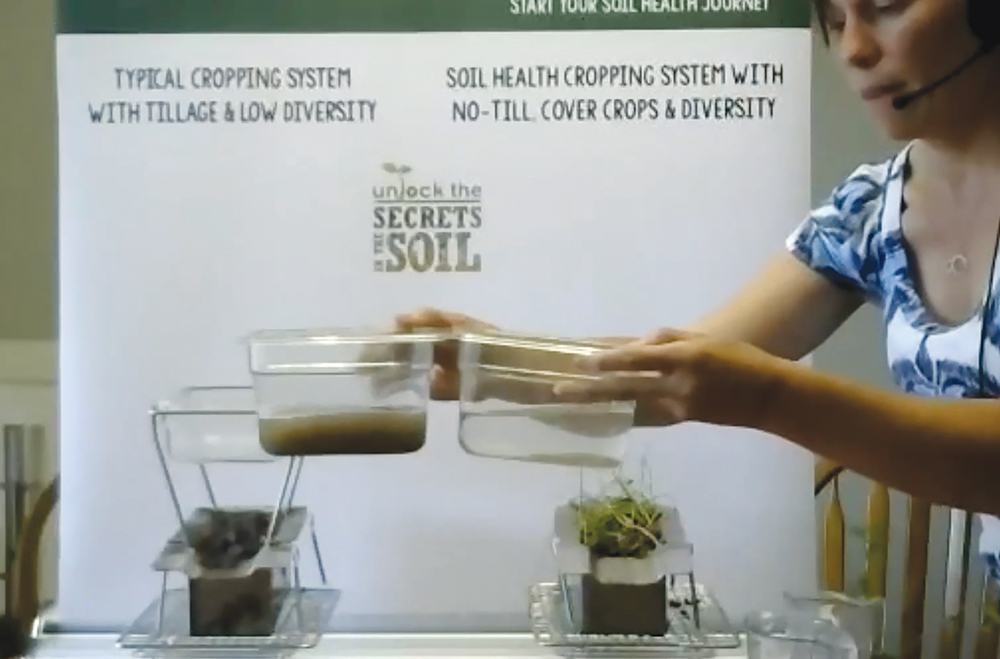

| Show a process, demonstrate an outcome or provide hands-on experience (e.g., a workshop, farm tour, field experience or demonstration) | livestream platform | ||

| Engage participants during meetings and webinars | interactive collaboration tools | ||

| Host ongoing networking or long-term online learning | networking platform | ||

| Provide live interpretation | interpretation add-ons |